Since the early days of the Republic, corporations have turned the Constitution itself into a shield against unwanted regulation of the economy. So long as the Supreme Court adheres to the view that corporate speech is no different than any other speech, any reform designed to limit the influence of corporations on the electoral process is vulnerable.

Editor’s note: This piece is part of our series on Corporations and Democracy, designed to continue the conversation initiated at a December 2020 conference by the same name sponsored by the Corporations and Society Initiative at Stanford GSB, and eight other schools and centers, including the Stigler Center at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. See the conference’s website for a summary of the event, the program, full videos, and other links.

American politics and elections received a shock in 2010 when the US Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in Citizens United, which said that corporations have the same First Amendment right as individuals to spend money on election advertisements. The decision triggered a new era of “dark money”—hidden, anonymous funds used to support candidates and skirt campaign disclosure laws—and has become a symbol of the outsized influence of business corporations on American democracy.

One reason for the power of American business that has often been overlooked is the long history of Supreme Court decisions, like Citizens United, extending the Constitution’s most fundamental rights to corporations.

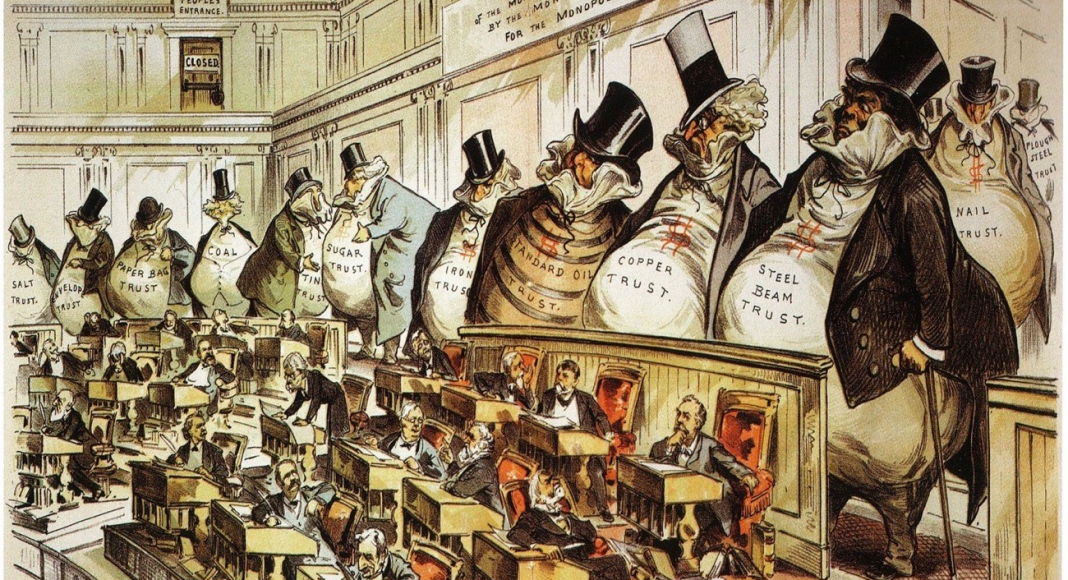

When Americans think of corporate power, they might conjure up an image of something like “Bosses of the Senate,” the famous late 19th century political cartoon by Joseph Keppler that shows a dozen colossal businessmen filing into the United States Senate through a doorway marked “Entrance for Monopolists.” The corpulent businessmen, labelled “Standard Oil Trust,” “Cooper Trust,” and “Sugar Trust,” tower over the Lilliputian senators, who are helpless against the corporate behemoths of the day. The power of corporations was political: they used their money and influence to dominate legislators and win favorable legislation.

Yet, throughout American history, corporations have also built and maintained their power through the courts and the judiciary. They have turned the Constitution itself into a shield against unwanted regulation of the economy.

It certainly did not begin with Citizens United. The first Supreme Court case on whether business corporations had rights under the Constitution was decided all the way back in 1809. To put that in perspective, the first Supreme Court cases on the rights of African Americans and women weren’t decided for another half-century (1857 and 1873, respectively). Americans are taught the Supreme Court is a bulwark for the protection of vulnerable minorities but African Americans and women lost most of their Supreme Court cases until the mid-20th century. In contrast, the corporation involved in the first corporate rights case, the Bank of the United States, won. And corporations have been winning an ever-expanding number of constitutional rights since—rights they use to challenge laws, enacted in the public interest, that regulate business. If the Bosses of the Senate fail to control the legislatures, there is always the Constitution and the courts to save them.

In the early 1800s, the Bank of the United States was the richest and most powerful corporation in the country. Nearly all American businesses were local concerns at the time, but the Bank of the United States was a truly national corporation, with branches from Boston to New Orleans. Due to its size and influence over the economy, the Bank of the United States spurred passionate opposition. In Georgia, opponents of the bank imposed a special tax on bank in an effort to force it to leave the state, and the bank sought refuge in the federal courts.

The Bank of the United States’ case presented a familiar question to critics of Citizens United: Are corporations people? Or, more specifically, are corporations “Citizens” under Article III of the Constitution? That provision effectively provides citizens a right to sue in federal court when they sue citizens of other states. This provision reflected the Framers’ fear that a state court might favor that state’s own residents over litigants from other states. The Bank of the United States, headquartered in Philadelphia, argued that it too would be prejudiced if forced to litigate the lawfulness of Georgia’s popular tax in Georgia’s state courts.

There was no evidence the Framers intended the Constitution to protect business corporations. The rights of corporations were never discussed at the Constitutional Convention or in the state ratifying conventions. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court, in an opinion by legendary Chief Justice John Marshall, ruled that the Bank of the United States did have the right to sue in federal court. Although corporations were not “citizens” as required by Article III, Marshall explained that the Constitution should be read expansively: “A Constitution, from its nature, deals in generals, not in detail. Its framers cannot perceive minute distinctions which arise in the progress of the nation, and therefore confine it to the establishment of broad and general principles.” The bank, and the people behind it, were entitled to the protection against parochial state courts. The Bank of the United States case was an early example of living constitutionalism and big, wealthy corporations—not vulnerable minorities—were the beneficiaries.

“So long as the Supreme Court adheres to the view that corporate speech is no different than any other speech, any reform designed to limit the voice of corporations in the electoral process is vulnerable.”

In the two centuries since that first corporate rights case, business corporations have won nearly every other constitutional protection a corporation could want: freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, due process of law, the right to compensation for property taken by the government, the right against double jeopardy, and the right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures, among others. The most controversial is the right to political speech recognized by the Supreme Court in Citizens United.

Business corporations first sought to establish that right nearly a century before Citizens United. Among the very first campaign finance laws were prohibitions on corporate spending on elections, enacted at the federal level in 1907 and in numerous states in the surrounding years. In the 1910s, when states were voting on whether to go “dry” in the runup to Prohibition, beer companies contributed to the opposition campaigns. When charged with violating campaign finance laws, the companies and their executives argued that the restrictions on corporate spending were unconstitutional. The courts, however, uniformly upheld the laws, with one explaining that corporations “must at all times be held subservient to the government and the citizenship of which it is composed.” To promote democratic self-government, government could limit corporate influence in elections.

Courts were willing to extend some rights to corporations but not all. The line they hewed to a century ago was that corporations were entitled to property rights but not liberty rights. Corporations were allowed to own property and the government could not take it without paying just compensation. They had basic due process and access to court rights that were essential to protecting their property. But corporations did not have liberty rights—i.e., rights of bodily autonomy, personal conscience, or political speech.

The boundary between property rights and liberty rights for corporations did not hold for long. In the 1930s, the Supreme Court ruled that newspaper companies were covered by the First Amendment’s freedom of the press even though they were corporations – and even though their publications were often political. In the 1960s, in the landmark case of New York Times v. Sullivan, the justices established the right to criticize public figures, and corporations like the New York Times Company enjoyed that right too. Then, in the 1978, in First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, the Supreme Court for the first time ruled explicitly that corporations had a right to spend money on at least some political campaigns.

The justice leading the charge in the 1978 case was Lewis Powell Jr. Just prior to joining the high court in 1971, Powell, then a board member of tobacco giant Philip Morris, had written a memorandum to the Chamber of Commerce outlining a program for the political mobilization of business. It was the era of Ralph Nader, and Congress had recently enacted groundbreaking legislation to protect the environment, consumer products, and highway safety. Powell thought reformers were unfairly targeting American business and his memorandum was a call to arms for business leaders to fight back to preserve the free market. The Powell Memorandum was widely shared, and today historians often credit it with inspiring the resurgence of politically active businesses in the 1980s and beyond.

In the Bellotti case, Powell transformed his memorandum into constitutional doctrine. The issue was whether corporations could make political expenditures to promote or oppose ballot measure campaigns. Writing for the Court, Powell rejected the dissenting justices’ complaint that the Court was extending to corporations broad free speech rights. Powell wrote that the issue was not whether corporations had free speech rights but whether the content of the corporations’ speech was political. If so, Powell explained, then the speech was protected regardless of who the speaker was.

The Bellotti ruling was limited; it only applied to ballot measure campaigns and, in a footnote, Powell suggested that campaigns for candidates were different. As a result, campaign finance laws restricting corporations from spending to elect officials remained good law. But Powell’s underlying approach to the First Amendment—that it protected the content of speech regardless of the speaker’s identity—would eventually overwhelm Bellotti’s limitations.

Perhaps surprising in light of the rhetoric of Citizens United’s critics, the Court in that case never said that corporations are people. Instead, the Court’s opinion echoed Powell’s principle that the identity of the speaker is irrelevant under the First Amendment. “Political speech is indispensable to decision-making in a democracy and this is no less true because the speech comes from a corporation rather than an individual.” It was a far cry from the courts of a century ago. To promote democratic self-government, government could not limit corporate influence in elections.

So long as the Supreme Court adheres to the view that corporate speech is no different than any other speech, any reform designed to limit the voice of corporations in the electoral process is vulnerable. There is every reason to suspect that each of the three Trump justices would affirm— if not expand—Citizens United. As a result, new campaign finance restrictions on corporations are likely to be struck down. Special rules for corporate political spending (such as shareholder consent requirements) may not be sufficiently neutral if only political speech is burdened. A constitutional amendment, of course, avoids the Supreme Court but faces daunting hurdles to ratification.

Mobilizing for a constitutional amendment or other legislation can, nonetheless, be useful for building political momentum for the cause of reform. The Supreme Court is not destined to be pro-corporate forever, so the job of reformers now is to formulate the arguments, do the research, and create a broader understanding of what they view as the proper role of corporations in society. And reformers should take a lesson from the corporations: constitutional revolutions are possible but may take centuries of persistent effort.