In an interview with ProMarket, antitrust scholar, lawyer, and businesswoman Dina Srinivasan explains why she believes that if users were given the choice to opt out, targeted advertising would go the way telemarketing in the US did after the introduction of the Do Not Call list, and expands on the similarities between the stock market dynamics that were exposed during the GameStop scandal and those of the Google-dominated ad market.

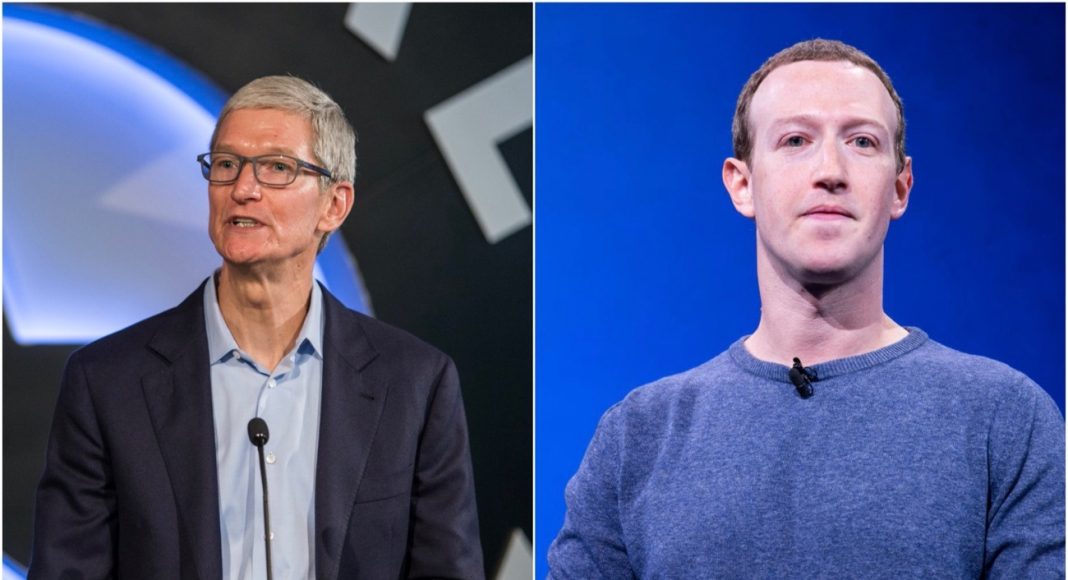

Late last month, Apple CEO Tim Cook used a speech he gave at a data privacy conference in Brussels to excoriate social media companies whose business models rely on collecting “vast troves of personal data” to sell targeted ads. “An interconnected ecosystem of companies and data brokers, of purveyors of fake news and peddlers of division, of trackers and hucksters just looking to make a quick buck, is more present in our lives than it has ever been,” said Cook. He didn’t mention any company by name, but his invocation of recommendation algorithms that steer users toward extremist groups and pointed reference to a “social dilemma” that could turn into a “social catastrophe” made clear which company he was referring to: Facebook.

The conflict between Apple and Facebook, which has been simmering for some time, became explicit and very public after Apple announced a privacy update to iOS. That update, now expected to roll out in early spring, would require apps that want to track users to get users’ permission via a pop-up that would explicitly ask if they consent to being tracked. Facebook, whose entire business model relies on tracking users online to sell targeted ads, protested with a PR campaign that included full-page newspaper ads and is reportedly preparing an antitrust lawsuit against Apple.

To learn more about what’s behind the Apple-Facebook spat and its potential implications for the future of online privacy, ProMarket recently caught up with antitrust scholar Dina Srinivasan. Srinivasan, a former advertising executive at WPP, the world’s largest advertising holding company, is currently a Fellow with the Thurman Arnold Project at Yale University. Her influential 2019 paper “The Antitrust Case Against Facebook” offered the most detailed account yet of how Facebook has repeatedly been able to extract monopoly rents from its users by not allowing them to opt out of Facebook tracking their behavior across thousands of sites and apps that aren’t Facebook. Her 2020 paper “Why Google Dominates Advertising Markets” was yet another authoritative account of the dynamics of the digital ad market, this time focusing on Google’s domination of electronically traded ad markets. Srinivasan helped draft the antitrust lawsuit that Texas and other state attorneys general filed against Google last year. (She also consulted on antitrust matters for news publishers in conflict with Google, including News Corp.)

In her ProMarket interview, Srinivasan explained why she believes that if users were given the choice to opt out, targeted advertising would go the way telemarketing in the US did after the introduction of Do Not Call list. She also expanded on the similarities between the stock market dynamics that were exposed during the GameStop-Robinhood scandal and those of the Google-dominated ad market.

[The following conversation has been edited and condensed for length and clarity]

Q: We’re about two weeks away from the Robinhood/GameStop craziness, and we have a little more clarity about what happened. Correct me if I’m wrong here, but this seems to be emblematic of something far larger in the political economy of digital platforms. What’s the biggest takeaway from this?

One big takeaway is, free is not free. This is not new thinking—we know that there’s no such thing as a free lunch. But consumers think that things are free because things are gamified to feel free. Robinhood is basically selling a product [called] “you can trade for free,” but this was one of those moments where, all of a sudden, consumers pay attention to the fine print and realize that Robinhood is routing order flow to a conflicted intermediary instead of a neutral financial exchange.

The practice is called payment for order flow (PFOF) and it’s controversial. One of the large intermediaries or wholesalers at the center of PFOP is Citadel. Basically, what happens with PFOF is that the broker (here, Robinhood) routes customers’ orders to Citadel in return for a kick-back. From a trading perspective, the concern here is that Citadel is not neutral like an exchange such as the New York Stock Exchange. Citadel has conflicts of interest. On the one hand, it is acting as a counterparty to customers’ orders. But at the same time, it has a financial interest in hedge funds like Melvin Capital that were shorting GameStop. So Citadel was responsible for fulfilling the Reddit traders’ buy orders, but at the same time, Citadel had a financial interest in the hedge funds that did not want the Reddit traders’ buy orders to go through.

It’s a controversy similar to the one Google is in the middle of in the ad trading market: Google is operating on the sell-side, on the buy-side, running the exchange where transactions clear, and preferentially routing order flow to itself. It’s clearing that order flow on its exchange. And it’s even buying and selling in the market in terms of selling its own YouTube advertising inventory. So it’s an intermediary that has conflicts of interest. That’s the second big takeaway.

Q: Can you elaborate on the similarities between these conflicts of interest of retail brokers and the ad trading market?

It’s not a direct comparison, because it’s not the exact same market structure—we don’t have payment for order flow and the redirection of order flow to intermediary wholesalers like Citadel in the advertising market. But it’s a similar problem. Payment for order flow is controversial in the US and not allowed in some countries because it doesn’t adequately manage conflicts of interest. Online advertising markets and Google’s role in them are highly controversial because of Google’s intermediary conflicts of interest. In the ad trading market, conflicts are completely unmanaged.

Large intermediary players like Google can operate on the sell-side and on the buy-side and also operate an exchange and clear trading on their exchange. Spreads are high, meaning trading is inefficient. And there is little trading transparency, which makes it hard for the free market to police the trading intermediaries.

“Activity that is prohibited and even criminal in the equities market, in the ad market it’s allowed.”

Q: Which brings to mind your paper from last year, in which you essentially argue that the Google ad market should be regulated just like the stock market.

Exactly. There are very similar problems and concerns about both, but in the equities market, conflicts of interest are regulated, insider trading is prohibited, and brokers have a duty to serve the best interests of their customers, buyers and sellers. We have new problems, like this PFOF Robinhood problem, but that problem is an outlier—overall, we regulate equities trading and the regulatory approach is to focus on the management of conflicts of interest. People that oppose PFOF argue that conflicts are not managed enough.

In the ad market, though we have centralized exchanges where ad space trades at lightning speed, and basically brokers on the sell- and buy-sides, we have no rules whatsoever governing conflicts. Activity that is prohibited and even criminal in the equities market, in the ad market it’s allowed.

From an economic policy standpoint and from an antitrust standpoint, it’s very peculiar that we would begin our journey into the 21st century with more and more markets migrating to high-speed electronic trading, but have one set of rules for trading on one type of exchanges (for equities, or even sporting event tickets or cryptocurrencies) and a different set of rules for other exchanges (for advertising space).

Q: The other Big Tech-related story these days is the public spat between Facebook and Apple. Your 2019 paper on the antitrust case against Facebook recalled a period when Facebook and other social media companies were competing on privacy. This Apple-Facebook fight is also ostensibly about privacy. What do you make of it?

We’ve got a few things going on here: What Facebook is upset about is Apple clamping down on the cross-site cross-app tracking of individual users. When you leave Facebook and you use a different app on your phone, does Facebook have the permission to continue tracking you across thousands of other apps? The focus of my Facebook research was that Facebook has market power and it’s extracting this market power from consumers by degrading their privacy, specifically by tracking them across apps.

The reason I focused on Facebook’s ability to track users across apps and sites was that there was a very long historical record of Facebook entering the market in 2004 and promising ‘We won’t track you off Facebook.’ It tried to backtrack on this promise many times when the market was competitive, but competition was strong enough that it prevented Facebook from extracting that consent from consumers. And then finally, as the market progressed and became less competitive, Facebook flipped the switch and started extracting that consent to track consumers across websites and apps. That right there is Facebook’s monopoly rent.

And now Apple is basically saying, we compete in a different market—selling the devices and hardware—so we can use our position to try to correct that monopoly rent. Apple understands that consumers don’t like cross-app tracking and it can use its position in the market to stop it. It’s basically giving users a pop-up notification on their phone that tells users that Facebook wants to track them on third-party apps. Apple asks: Do you consent to this or not? They’re migrating consent from a 73-page terms and conditions document that nobody clicks on and nobody understands to a pop-up window to see if consumers really do consent to this.

What Facebook is now very concerned about is that consumers are going to say no. And it should be, because it has some experience with this. Back in 2006, Facebook showed pop-ups that asked if users were willing to share data from a third-party site with Facebook and users revolted. Facebook had to do an about-face and issue an apology, and they had to continue to compete on privacy. And so it’s very reasonable for Facebook and others to be concerned that Apple is going to use its position as the maker of the device in consumers’ hands to inform consumers what’s going on and try to extract clear consent.

One of the interesting things that are going on here is these large companies have argued that consent is valid because consumers consent through the terms and conditions, and the courts have followed this path. But how real is that consent? And if Facebook loses 80 percent of consumer consent when Apple puts it in a pop-up, what does that tell lawmakers and policymakers about the systemic failure of bilateral negotiations between consumers and companies when it comes to terms and conditions? That’s another really fascinating aspect of what’s happening here: it’s a live experiment.

Q: So you’re staunchly in the camp that believes people will choose to opt out of Facebook’s tracking.

I firmly think that a ton of people are going to select “No.” The reason that Facebook is concerned is because it too thinks users will say no, and then the advertising that Facebook sells is going to be less effective.

Facebook’s position here is that Apple is going to hurt small businesses, because small businesses rely on buying targeted advertising from Facebook—a sort of populist angle. It’s not a great PR strategy because one could take that argument to unreasonable ends: If you put a surveillance camera in people’s living room or surveillance camera inside people’s cars, for example, you’ll know more about what they like, what their habits are, how they consume. The more that you degrade people’s privacy, the more effective advertising is going to be. Should we let Facebook do those things because it improves small business advertising? Is that really Facebook’s position?

The point is that economic relations should be built on consumer consent. You don’t steal consent from consumers. Don’t tell me what’s good for me—allow me to consent through the dynamics of a competitive marketplace. Facebook’s argument fails because it does not address the role of consumer consent, and that type of argument fails in a democracy and in a free market economy.

Businesses made the same argument in the late 1990s and early 2000s when they were fighting the Do Not Call list in the US. We used to have telemarketers call your home phone all the time. They loved to interrupt you during dinnertime, because that’s when everybody was sitting at home together. There were all kinds of inefficiencies and physical costs that weren’t measured and were decreasing the utility of the phone.

And so lawmakers tried to put together a Do Not Call list to allow consumers that wanted to opt out to say “Stop!” There were lots of economists and companies at the time that were making the argument that allowing consumers to opt out of receiving these calls is inefficient because consumers don’t know better and the more information we give consumers through these telemarketing calls, the more they’ll be able to make informed decisions. Eventually the Do Not Call list passed, the entire country opted out, and the entire telemarketing industry crashed. The whole thing was an artificial market not predicated on consumer consent that reflected market failure.

That’s what people in the advertising industry are concerned about: that the behaviorally targeted online ad market is another runaway market that is not predicated on consumer consent and that it could similarly crash.

“That’s what people in the advertising industry are concerned about: that the online ad market is another runaway market that is not predicated on consumer consent and that it could similarly crash in terms of behaviorally targeted advertising.”

Q: Many people find it somewhat ironic that Facebook is now reportedly planning to file an antitrust suit against Apple for not allowing it to track users.

It is a bit ironic because a lot of small businesses have for a very long time complained that Facebook blocks them from tracking users viewing their ad campaigns. Facebook is complaining that they want certain data from the Apple ecosystem in order to run their business efficiently—but a lot of small businesses complain that they want data from the Facebook ecosystem in order to run their small business efficiently. And so it’s kind of interesting that Facebook is turning around and complaining that it’s an antitrust violation when Apple does something along similar lines.

Q: Apple has put a lot of effort into branding itself as a defender of privacy, but after all, it collects user data too.

Aside from Facebook, a lot of market participants right now are standing on the sidelines watching this Facebook-Apple spat, saying “Apple, you’re just self-preferencing; you’re making it hard for users to give Facebook data but making it easier for yourself to collect data on users for similar purposes.” Apple has something called the SKAdNetwork, which allows third-party advertisers to tap into some data to track their ad campaigns. And it has something else called the Apple Ads Attribution API, which allows its own advertisers that are buying advertising directly from Apple to receive a superior data set. What’s unclear is whether these differentiations in data access are temporary or whether that’s really Apple’s position with respect to data.

Q: Which brings us back to your Facebook paper and to that period when Facebook was forced to compete on privacy. What does it mean that we now see tech giants competing with each other again over who’s better when it comes to user privacy?

Apple doesn’t compete directly with Facebook; it is in a vertical relationship with Facebook. I think that Apple is competing in the sense that it is trying to compete on the basis of reducing or nullifying Facebook’s monopoly rent in the market, and it sits in a vertical position to Facebook, so it’s able to do that. In other words, Apple is able to win consumer allegiance and goodwill by pushing back on what Facebook is extracting from people in terms of privacy.

Apple right now has a lot of brand equity around user privacy. But as a user and as a consumer of Apple’s products, I find it disingenuous, for example, that my iPhone has one section where I can control Siri settings, but if I turn Siri off in that section, Siri is automatically turned on anyways in every app and that there’s no universal off switch. If I were on Apple’s board, I’d advise the company not to do things like that. Consumers are sensitive when it comes to their privacy and brands can rapidly lose brand equity over privacy concerns.