Large institutional investors have been accused of not doing enough to reduce CO2 emissions. However, a new study finds that firms like BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street Global Advisors try to influence CEOs of companies in their portfolio to reduce their CO2 emissions via interactions other than voting. The higher the ownership by the Big Three in a company, the authors find, the greater the reduction of its carbon emissions.

In recent years, top asset management firms have come under fire from climate change activist investor groups. They’re accused of being lukewarm in the face of environmental challenges and of failing to pressure the companies in their portfolio to reduce their impact on the environment.

Some of these activist groups have even gone so far as to track their votes on boards and have found that oftentimes these large institutional investors don’t support the initiatives proposed by other shareholders to reduce the environmental impact of their portfolio companies. But are all these accusations justified? What role do big investors actually play in the fight against CO2 emissions? Are the promises they make effective, or are they purely greenwashing?

The “Big Three” and Carbon Emissions

In our study “The Big Three and Corporate Carbon Emissions Around the World,” forthcoming at the Journal of Financial Economics, we try to shed some light on this debate. Specifically, we analyzed the role of the three largest asset managers in the world—BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street Global Advisors—in reducing companies’ carbon emissions.

The current interest in the Big Three responds to the unique combination of characteristics of these investors. The first of these characteristics is their size; they manage an enormous (and growing) amount of investments. The second distinctive characteristic of the Big Three is that most of the investment vehicles sponsored by these investors are passively-managed.

The role of large passive investors in the economy is a subject of ongoing debate. While acknowledging the advantages of index fund investing in terms of diversification and lower management fees, some commentators have raised some concerns about the Big Three, including issues related to pricing efficiency and trading behavior, anti-competitive effects, and underinvestment in stewardship. In contrast to these issues, it is also argued that fund sponsors compete not only on fees but also on returns. Moreover, recent research suggests that passive investors have meaningful monitoring incentives when it comes to cross-cutting issues such as sustainability and certain aspects of corporate governance in which large investors can exploit economies of scale.

“By pushing firms to reduce CO2 emissions, the Big Three seek to attract or retain investment clients that are sensitive towards environmental concerns.”

Beyond possible altruistic reasons, the Big Three could have several economic incentives to engage with firms on environmental issues. One potential motivation is that these large investors believe that reducing CO2 emissions increases the value of their portfolio. As suggested by survey evidence, a non-trivial number of institutional investors believe that climate risks have financial implications for their portfolio firms and that the risks have already begun to materialize, particularly regulatory risks. An alternative motivation is that, by pushing firms to reduce CO2 emissions, the Big Three seek to attract or retain investment clients that are sensitive towards environmental concerns.

What Does the Data Say?

Theoretically, a shareholder exercises their power in three different ways: by buying shares (or by ceasing to do so), by exercising their voting rights at shareholders’ meetings, or through engagement with the management team of the investee company, expressing their opinions and concerns.

In our research, we worked with a sample made up of a total of 42,193 observations corresponding to approximately 8,000 firms around the world, of which we studied two key variables:

1) Data on corporate CO2 emissions provided by Trucost, which collects data from more than 13,000 companies each year (representing approximately 99 percent of the world market capitalization)

2) The Big Three’s engagement actions with the companies in their portfolio as published by the asset management firms themselves in their investment management reports (Investment Stewardship Reports or “ISRs”).

The first thing we found is that the Big Three are more likely to engage with companies with the highest carbon emissions. In fact, the Big Three focus their engagement on large companies (those with greater potential to have an effect on global carbon emissions) and in those in which they have a more significant stake (and, therefore, a greater capacity to influence). The data reveals that the greater the probability of the Big Three meeting with CEOs, the higher the carbon emissions recorded by the company in the previous year. This result supports the thesis that, indeed, the Big Three try to influence the most polluting companies to reduce their CO2 emissions.

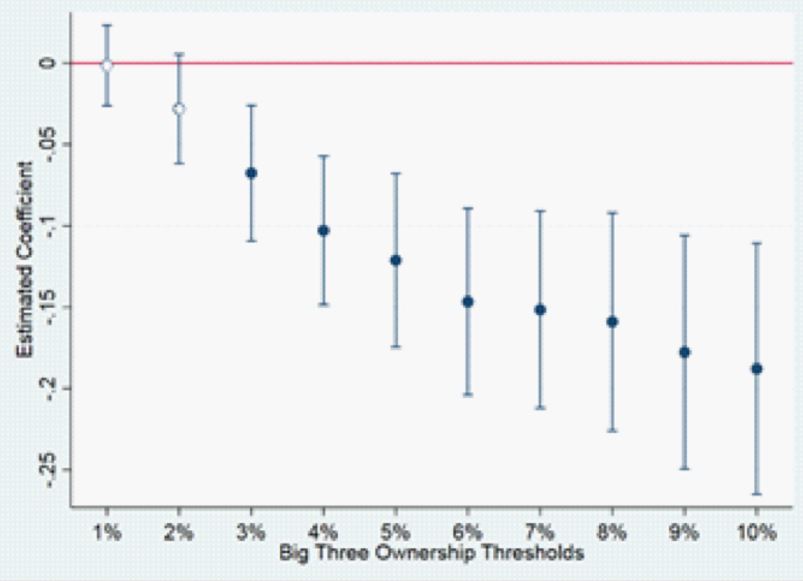

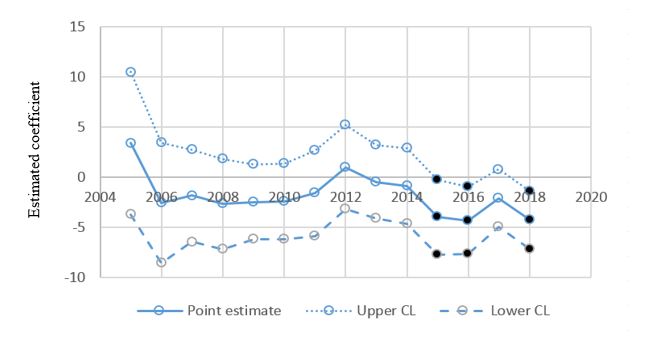

The question is: Do these interactions have a tangible and appreciable impact on reducing emissions? The answer, according to our analysis, is that the greater the influence exerted by the Big Three, the more carbon emissions are reduced. This pattern is corroborated when we introduce plausible sources of exogenous variation into the analysis, such as the changes in Big Three ownership associated with inclusion in the Russell 1000/2000 indexes, and increases in intensity the greater the commitment of these asset managers is to reducing CO2 emissions.

The influence of institutional investors in swaying the companies to reduce carbon emissions in their investment portfolios is a relatively recent phenomenon, consistent with an increasing popular demand following the 2015 Paris Agreement, but it has already resulted in a statistically and economically significant reduction of carbon emissions (see figure 1).

Our findings also indicate that the higher the ownership by the Big Three in a company, the greater the reduction of its carbon emissions (see figure 2). A phenomenon that can be seen from a relatively low shareholding of just 3-4 percent, and that intensifies as ownership levels increase.