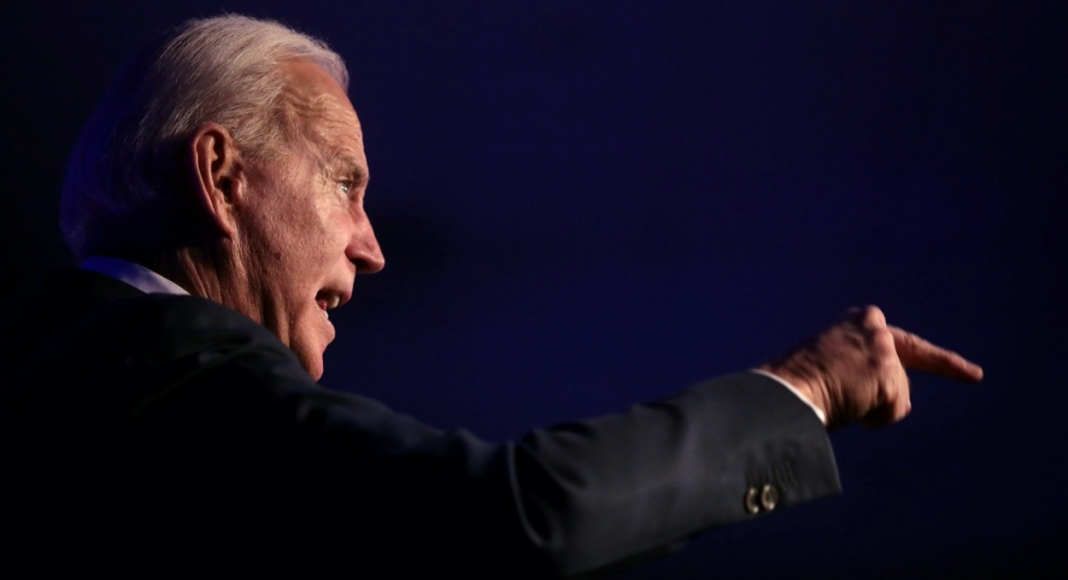

How will US antitrust policy look under President Joe Biden? We caught up with four antitrust experts—Jonathan Baker, Zephyr Teachout, William Kovacic, and Teddy Downey—to discuss what antitrust agenda the new administration should pursue.

Among the monumental challenges facing the incoming Biden administration is how to address America’s massive—and growing—concentration problem. Faced with rising income and wealth inequalities, a dysfunctional health care system, an unaccountable tech industry, and an economic crisis that is proving to be catastrophic for small and medium-sized businesses, President-Elect Joe Biden will face a lot of pressure to present an antitrust agenda that is much more aggressive than his predecessors’.

How Biden approaches that challenge, and whether he will address it in any meaningful way, remains to be seen. Antitrust policy, front and center during the Democratic primary season, wasn’t a big part of Biden’s presidential campaign, but some statements made by Biden and his staffers—like his criticism of Facebook and his call to revoke Section 230— suggest he will be less friendly toward Big Tech than the Obama administration, in which he served as Vice President for eight years.

To better understand what antitrust agenda the new administration can—and, more importantly, should—pursue, we caught up with four antitrust experts: Jonathan Baker, Zephyr Teachout, William Kovacic, and Teddy Downey.

[All conversation have been edited for length and clarity]

Jonathan Baker: Strengthen Deterrence, Advocate New Legislation, Create Competition Office in the White House

Jonathan Baker is a Research Professor of Law at the American University Washington College of Law and a former chief economist at the FTC (1995-1998) and the FCC (2009-2011). He is also the author of the 2019 book The Antitrust Paradigm: Restoring a Competitive Economy (Harvard University Press).

Q: What are the main antitrust actions that the Biden administration should take?

The overriding goal is to strengthen antitrust, because market power is a growing problem in the economy. There are a variety of things the administration could do to pursue that: working with the courts, advocating new legislation, and creating a new competition office in the White House.

Putting aside the prospect of new legislation, the antitrust agencies face a substantial enforcement challenge: they need to do more while operating in a difficult judicial environment for litigating cases. It’s not a hopeless prospect, but it will be hard. The challenge is probably greater than what Thurman Arnold faced in 1938, when he took charge of the Antitrust Division and began to ramp up enforcement and strengthen deterrence of anticompetitive conduct, because the Supreme Court in that era proved sympathetic to what Arnold was trying to do.

The FTC and DOJ have a number of tools they can use to make progress. To push the courts, they should adopt an approach that involves integrating enforcement actions with amicus briefs and policy guidance. They should think systematically about identifying industries where they can make a difference, and about the types of harms that require more enforcement attention.

Enforcers still win cases, even in the current judicial environment, especially when they uncover strong facts. Even in exclusionary conduct cases, where there might be the least consensus about how to proceed, the government has prevailed in several appeals court cases over the past two decades. They lost a couple, but they were successful with Microsoft, Visa, Dentsply and McWane. There’s case law on which to build.

Q: In the recent Equitable Growth report you co-authored, you also recommend that the next administration try to pass new antitrust legislation.

That’s correct. That would be a high priority. I would guess new legislation would be more likely with a Democratic Senate, but it could also be enacted with a Republican Senate given the bipartisan support in Congress for strengthening the antitrust laws. Congress may not act quickly but new legislation is important and would make a huge difference.

Q: Is there a particular type of legislation that you have in mind?

The general idea is to strengthen deterrence. Among other things, Congress should consider reversing court decisions that get in the way of deterrence and increasing the budgets of the antitrust agencies. In the report, we recommended an increase of $600 million, to account for the discrepancy between static appropriations levels and the way the economy and our competitive problems have grown over time.

Q: You also recommend that the next administration “rethink fundamental questions surrounding US antitrust laws and their enforcement.” What are these fundamental questions?

On enforcement, the new administration should aim to work systematically to strengthen deterrence, rather than just reacting to events. It’s very easy for enforcers to sit back and focus on mergers when they get filed, and only occasionally consider enforcement matters that are brought to their attention in other areas. The challenge is to think strategically about how to increase deterrence in a systematic way. Part of doing so involves targeting different kinds of industries and types of harm, and part of it involves a systematic effort to encourage the courts to strengthen antitrust rules.

Q: One of the interesting propositions in the report is that the next administration should establish a new competition office within the White House. What would be the benefit of that?

A wide range of government agencies other than the FTC and the Justice Department make decisions that affect competition—the Food and Drug Administration, the Patent and Trademark Office, the Transportation Department, communications, energy, and financial regulators, etc. These agencies often are asked to consider multiple goals in making their decisions, and they can be influenced by the industries they regulate to act in ways that don’t foster competition, or even impede it.

Our report encourages the new administration to make it a government-wide priority to promote competition and coordinate the actions of government agencies with overlapping authority to do that. We thought that in order to give that review institutional clout, it would be best to house it in a new White House office. That office would make competition concerns more prominent throughout the government and influence all the agencies to do more to make markets more competitive.

“The new administration should aim to work systematically to strengthen deterrence, rather than just reacting to events.”

Jonathan Baker

Zephyr Teachout: The Case for a Fundamental Switch in Our Thinking About Antimonopoly

Zephyr Teachout is an Associate Professor of Law at Fordham Law School and one of the most prominent voices within the New Brandeis movement (She is affiliated with the American Economic Liberties Project, or AELP). She has written two books and dozens of articles on the intersection of private law and the law of democracy, her latest book being Break ‘Em Up: Recovering Our Freedom from Big Ag, Big Tech, and Big Money (Macmillan 2020). Her anti-corruption research has been cited in state and federal courts as well as in the Supreme Court.

Q: What are the main antitrust actions that the Biden administration should take?

It’s important to continue the Google case, of course, and there are ongoing investigations and promising new investigations that should be undertaken. But I actually think the key is starting a few steps back: for 40 years, agencies have misinterpreted existing antitrust law.

In 1890, 1914, 1921, and many other points, Congress gave the president the task—through the FTC, the Department of Agriculture, and other agencies—of protecting workers and small businesses against abusive and extractive behavior. And since 1980, presidents have purposely misread that task and have been announcing that their task is to serve low consumer prices. So the first thing that Biden should do is clearly direct his agencies to do the job they were designed to do, which is to stop theft and abuse by big monopolists.

Right now, monopoly is the operating system of our society and is leading to radical inequality and enormous suffering, which has been compounded manyfold by the pandemic. The job of the president is to make sure that a fair, open, competitive, and flourishing society that works for workers and small businesses and communities is the operating system of our society.

I strongly advocate for the legislative changes that [Congressman David] Cicilline will push for. But that’s where I would start: we need to do a very fundamental switch in the understanding of antimonopoly laws and the role of the presidency. We actually haven’t had a president who has even tried their substantial rulemaking authority to really take on the democratic and economic threat of big monopolists since the Chevron Deference.

Q: You mentioned legislative changes as well?

The Cicilline report provides a really powerful blueprint for moving forward and I hope and expect we will see that report will turn into legislation fairly soon. It’s going to be critical for Biden to be openly supporting [of] that legislation.

In 2009, Barack Obama signed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, overturning terrible Supreme Court decisions on equal pay. It’s harder with this Senate, but Biden should take that memory and have the ambition to sign a bill overturning terrible neoliberal Supreme Court decisions on antimonopoly.

The reason it’s important for him to put some muscle behind and not be passive is not only because it’s good but also because it’s wildly popular. All recent polling shows that antitrust doesn’t act like other political issues—you don’t see the same left/right divide that you do in many other issues. In fact, in some areas, you see a majority of rank and file Republicans supporting a president who’s going to take on Big Tech and Big Cable. Biden speaking directly to people in the rural communities and urban communities about the devastation of black businesses and the devastation of farmland and the devastation of local pharmacies, doing the leadership work of showing that the rural/urban divide isn’t there when it comes to monopolization, is not only good but also great politics.

Another reason to do it is that we need stimulus desperately. We just saw last week how antitrust is stimulus: a combination of the Cicilline report and the Epic lawsuit made Apple say it’s going to charge developers 15 percent instead of 30 percent. Now, the total amount of money here is pretty small, but we’re just in the early stages of the lawsuit and you’re already seeing wealth redistribution.

Q: The next administration is going to have to deal with a very conservative Supreme Court and there’s a good chance the Senate will stay in Republican hands. Does that limit the scope of what the Biden administration can do?

We have a tendency to look at the Supreme Court through the lens of it being a democracy killer: the Court repeatedly strikes down laws as unconstitutional, creating a very significant barrier to some key forms of laws against corporate spending in elections.

Antitrust is entirely different. The Court does not strike down laws, it just grossly misinterprets them. It is not as significant a challenge. These are statutory questions. Until the Court starts striking down antitrust law on First Amendment grounds, which I wouldn’t put past them, we’re really in statutory interpretation land.

What that means is that the real challenge is the Senate, and there’s a lot we don’t know. But a unilateral surrender and not taking the antitrust fight to the Senate is both a moral failure and a tactical failure: a moral failure because people are desperate and they’re getting abused, and to not stand up to protect people from abuse is immoral; and a tactical failure because, again, this is wildly popular.

“The first thing that Biden should do is clearly direct his agencies to do the job they were designed to do, which is stop theft and abuse by big monopolists.”

Zephyr Teachout

William Kovacic: Win the Google and Facebook Cases, Increase Salaries in Antitrust Agencies

William Kovacic is the Global Competition Professor of Law and Policy at the George Washington University Law School. He is a Non-executive Director of the United Kingdom’s Competition and Markets Authority. From 2001 to 2004, he was the General Counsel at the Federal Trade Commission, in which served as a commissioner from 2006 to 2011 and chaired from March 2008 to March 2009.

Q: What are the main antitrust actions that the Biden administration should take or the main antitrust areas that the administration should focus on?

Certainly, a top priority would be to continue and succeed with the big cases that are underway (e.g., the Justice Department monopolization case against Google) or will be running soon (possibly a Federal Trade Commission monopolization case against Facebook). One big priority is to carry those home. Related to that, there are other big FTC cases involving big tech or information services platforms. I would press ahead with seeking Supreme Court review of the Ninth Circuit decision in the FTC’s monopolization case against Qualcomm. The FTC also is in the midst of an appeal of its 1-800 Contacts decision, which is an important information services case. And the FTC is litigating another important information platform case against Surescripts.

So there’s a significant ongoing agenda. If you can win a suitable number of these cases, you’ve gone a long way toward setting the doctrine in a better place than it is now. Those are tough cases.

Another priority is to rethink the resourcing of the agencies. A major priority should be to increase the expenditures for the FTC and Justice Department Antitrust Division. To my mind, it’s not simply a matter of adding more people; I would rethink the compensation scale.

Q: Can you elaborate on that?

The civil service pay scale that binds the FTC and the DOJ is desperately behind what it should be. The salaries for individuals have to be raised dramatically. I don’t see how the agencies can sustain an adequate level of capability to prevail against the corporate opponents it’s now encountering, or will soon face, in the cases I have mentioned if the government continues to pay the existing civil service scale. This is especially true if we’re going to slam shut the revolving door between government and the private sector.

One approach is to start with an experiment at the FTC. We could raise FTC salaries to what some of the financial services regulators, such as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, now pay. The CFPB pays a salary scale about 20 percent more than the civil service scale. That would be a major inducement for key personnel to stay longer at the FTC.

In the proposal that Alison Jones and I made in April to the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law, we recommended giving the FTC $1 billion per year for 10 years and dramatically increase the salaries that you’re paying and see how it performs with that level of support.

If Congress is not going to change the compensation scale, the antitrust agencies perennially will be engaged in a desperate, unavailing race to defeat opponents who can bring better resources to bear on these cases.

Q: Speaking about an ambitious agenda, we’re nearly two months after the House Judiciary Report on Big Tech came out. Should the Biden administration embrace the House report?

Parts of it. If you prosecute the Facebook case and the Google case successfully, you will have achieved major objectives of that report. If you win these cases, you’ve done a lot to reset the boundaries of the system and re-establish the credibility of the system. This is a fairly dramatic step ahead.

It’s worth thinking about what kinds of regulatory adjustments you want to add to the system. That is, do you want to deliberately extend the FTC rulemaking authority to encompass the regulatory suggestions in the proposal? Create an entirely new institution to regulate tech? That’s worth having a debate about, perhaps part of a larger discussion about what we want the configuration of the antitrust system as a whole to be.

I think it’s also worth considering amendments to the merger review process, merger review standards, and doctrine governing dominant firms. The US antitrust system has unduly narrowed the target that plaintiffs have to hit when challenging dominant firm conduct and mergers. The horizontal merger guidelines were reset ten years ago—now would be a good time to revisit them and ask if this vision is consistent with what we want to do.

Q: Outside of Big Tech, are there other sectors or areas that the incoming administration should focus on?

Public procurement. The focus on Big Tech tends to deflect attention away from how important procurement is as a focus for government expenditure and influence upon competition. Government bodies are spending and are going to continue to spend lots of money on recovery. I would make procurement a major priority, given that so much of what the government buys has so much significance for the lower half of the income demographic. If you want to deliver benefits to the dispossessed, you improve the procurement program, because they feel it the most when it doesn’t work.

Another major priority improving the US antitrust system should be to join up the work of the DOJ, the FTC, and the states more completely. Despite some collaborative efforts, they work too much in isolation– certainly by comparison to the cooperation of the European Commission and the European Union’s Member States. If you built a better network of cooperation, each of the public antitrust agencies would be better off because they would have the benefit of this more broadly shared learning. The US system is operating well inside the production possibilities frontier, and better interagency cooperation and planning could move us toward the frontier.

Q: From the transition teams that Biden has put in place, his first appointment, and his own legislative record, do you see the incoming administration pursuing an ambitious antitrust agenda?

I do. There has been so much criticism of the Obama antitrust program of which Biden was a part. The modern critique has been extremely hostile to the Obama antitrust program, which is often presented in the literature as being far too timid.

After Barack Obama promising a great extension of antitrust enforcement as a candidate for the presidency in [2008], the DOJ and FTC failed to fulfill some of the candidate’s most important commitments, especially in their enforcement against dominant firms. I think there will be an awareness in the administration that they have something to prove. As a consequence, I think there will be an effort to do more, especially if you bring Obama alumni back into the government. They’ve been hammered now for several years for being shamefully inadequate. This will be a chance for them to do better, and I think those people will take those jobs with a sense of much greater obligation to do more than they did the last time and come up with a more ambitious program.

“If Congress is not going to change the compensation scale, the antitrust agencies perennially will be engaged in a desperate, unavailing race to defeat opponents who can bring better resources to bear on these cases.”

William Kovacic

Teddy Downey: Antitrust Policy Under Biden Will be Different Than Obama

Teddy Downey is the CEO and executive editor of The Capitol Forum, an investigative news and legal analysis publication that provides information for government and industry decision-makers. Before that, he was a Senior Vice President at MF Global’s Washington Research Group, where he provided education policy and antitrust policy research for institutional investors.

Q: What is our best estimation of how Biden’s antitrust agenda might look like once he enters the White House?

I think there’s a couple of things to keep in mind. One is: what are the indicators that we have? You have some of the stuff that Biden said on the campaign trail—that he wants to get rid of Section 230, etc. That’s one indicator that you should maybe expect more aggressive enforcement than we had during the Obama administration. I don’t know how reliable that really is, because presidents break their campaign promises all the time.

The next thing to look at: What are the cases and the general drift of antitrust right now? There is an ongoing case against Google. That’s a landmark case. We’re expecting a case against Facebook, and then likely down the road one against Amazon as well. All indications are that the Biden administration will pursue those cases as well. That’s a huge deal. We haven’t had a big monopolization case since Microsoft.

Another set of indicators is who’s on the transition team. The names on the transition team that have to do with antitrust—Bill Baer and Gene Kimmelman—I would call them sort of Obama-era neoliberals, not particularly aggressive names. Them being on the transition team for the FTC and DOJ are somewhat of an indication that you’re not going to get aggressive antitrust enforcement, although that is somewhat offset by some of the more populist names that were on the other transition teams for the Treasury and the Fed, people who are in the break-up-the-banks model.

Lastly, I would say that the agenda on antitrust will be set for Biden by the Democratic FTC commissioners—Rohit Chopra and Rebecca Kelly Slaughter—because they will be relied upon heavily to transition from the Trump administration to the Biden administration. They have very different views from the Trump administration and the Obama administration on merger enforcement, monopolization, rulemaking, a whole host of very interesting policy issues. That’s a very different tone from the Obama administration and suggests that there will be more rigorous analysis, less status quo and less reliance on ideas and analyses that maybe haven’t been effective, and more use of wide-ranging tools in the FTC’s antimonopoly toolbox.

Q: The transition teams do seem to be a mixed bag, with some corporate-friendly names and reformers who are on the more radical side. What should we read into that?

It’s enough of a mixed bag at this point that you can’t read too much into it. To the extent that the tech industry will have a lot of influence, we haven’t really seen that it would be in the places where they would be most concerned about: law enforcement and regulation. We haven’t seen any indication that Biden will back off of the Google or Facebook cases.

Q: Do you think the growing bipartisan anger toward Big Tech means that the next administration can be more aggressive?

On the one hand, you have this visceral understanding of the power that these companies have over voters, elected officials, politicians. People in the government think that these companies, Facebook and Google, have too much control—they see it in a very visceral way when the companies have control over their ability to win an election. So I think there’s just this practical desire to solve this monopoly problem and also, they see this issue as a political winner. And then you also have a growing consensus around the world that something is missing or something is wrong and needs to be dealt with. All of that creates a very different environment than what we had during Obama.

” We haven’t seen any indication that Biden will back off of the Google or Facebook cases.”

Teddy Downey