Section 230 has faced scrutiny from President Donald Trump, the FCC, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, the US Congress, and even President-elect Joe Biden, who previously said that it should be repealed in its entirety. However, it seems that any changes to Section 230 will most likely come from the courts, which continue to adjust and modify its interpretation.

As of this writing, it appears that Joe Biden will become President in January. President Donald Trump’s personal war on social media—embodied in last May’s “Executive Order to Prevent Online Censorship”—should wind down over the next few months.

However, this does not mean the end of trouble for Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and other social media platforms. The days when Democrats embraced Silicon Valley companies as examples of American technological exceptionalism and models of innovation have long passed. The recent, extremely-detailed report of the House Judiciary Committee on anticompetitive conduct by dominant digital platforms sets out an ambitious agenda of potential legislative reforms designed to promote competition in the digital platform space. We can expect the antitrust lawsuit brought against Google by the Trump Department of Justice (DOJ) Antitrust Division to continue—perhaps even expand—under the Biden DOJ. We should also expect continued interest in Congress and at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to expand existing privacy protections for consumers, although it remains to be seen whether Democrats and Republicans can come to an agreement on privacy legislation after years of trying.

In one important area, however, we will see a very significant change in policy. President Trump has repeatedly accused social media platforms of using content moderation policies to discriminate against himself and conservatives in general. Although no evidence supports the allegations of anti-conservative bias, Trump and fellow Republicans have focused extensively on these accusations—especially in response to labeling content from Trump as factually incorrect. In retaliation, Trump has targeted Section 230 (47 U.S.C. §230), the statute that insulates social media companies (and other providers of “interactive computer services” as defined by Section 230(e)) from liability relating to hosting, editing or taking down third-party content. Specifically, through a Petition for Rulemaking filed by the National Telecommunications Information Administration (NTIA), President Trump asked the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to interpret Section 230 to require content moderation “neutrality” as a condition of the statute’s liability protection.

In other words, under the proposed FCC rules, social media providers (and other interactive service providers—a class sufficiently broad to include any provider of online services, from cloud storage to ISPs) would risk liability for any labeling content as false or questionable, taking down content deemed objectionable, or any other action conservatives find objectionable and therefore “biased.”

A core group of conservative pundits and prominent Republicans accused social media platforms of “liberal bias” even before the Trump Administration, and we can expect these accusations to continue. But beyond the “bias” allegations, a wide variety of critics have called on Congress to modify Section 230 in the belief that Section 230 permits digital platforms, particularly social media, to engage in a wide array of unsavory behavior, from promoting hate speech to sex trafficking. The EARN IT Act, which has 16 bipartisan sponsors at the time of this writing, is just one of several legislative proposals taking different approaches to Section 230 reform.

“It seems far more likely that a judicial consensus to narrow Section 230 will emerge before any sweeping legislative or regulatory change.”

Ultimately, it seems most likely that the courts will continue to adjust and modify the interpretation of Section 230. Justice Clarence Thomas recently wrote a lengthy concurrence on a denial of certiorari on how the judiciary should revisit the early precedents from the late 1990s giving Section 230 its current dimensions. Even if appellate courts do not directly revisit early precedents giving an expansive interpretation of Section 230, recent decisions have approached eligibility for the liability shield with increasing sophistication and precision. It seems far more likely that a judicial consensus to narrow Section 230 will emerge before any sweeping legislative or regulatory change.

The FCC Rulemaking Likely Dies with a Whimper

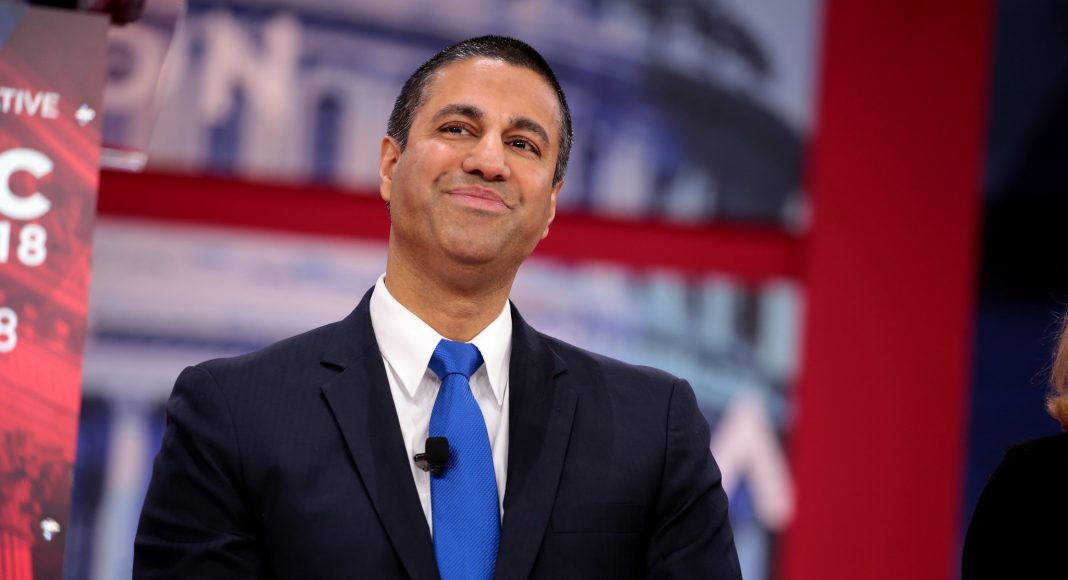

FCC Chairman Ajit Pai announced in October that he would proceed with the rulemaking requested by the NTIA. Others have explained why—despite the reassurances of the FCC’s General Counsel—the FCC probably lacks statutory authority to adopt the rules requested by NTIA. But it now seems unlikely that even the proposal will come to a vote. Pursuant to long-standing tradition, the Democratic Chairs of the House Commerce Committee and the Telecommunications Subcommittee have sent a “pencils down” letter to the Chairman Pai, requesting that the FCC undertake no new controversial matters pending the transition to the new Administration. Although nothing requires him to follow this direction, Pai insisted in November 2016 that outgoing Democratic Chairman Tom Wheeler refrain from moving forward any controversial items. It therefore seems likely that Pai will follow this tradition and refrain from trying to move the 230 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) forward.

Even if Pai decided to move forward, Pai would still need to have the NPRM drafted and circulated before the end of the year, and would need three votes to approve the item before the President appoints a new Chair of the FCC on January 20, 2021. At the moment, it seems unlikely that Republican Commissioner Michael O’Reilly would provide the third vote. O’Reilly previously expressed doubt about the legality of the FCC regulating under Section 230, prompting President Trump to withdraw O’Reilly’s nomination for another term.

In place of O’Reilly, President Trump nominated Nathan Simington—whose chief qualification appears to be his work at NTIA drafting the 230 Petition for Rulemaking. Undoubtedly, Simington would provide a third vote for an NPRM. Despite pressure from Trump to push through Simington’s nomination (including a Twitter campaign in support directed against key Republican Senators), the Senate has little time to confirm Simington before adjourning at the end of the year. Once Congress adjourns, the nomination expires. O’Reilly’s term ends, but he has no Republican replacement.

Even if we assume that Chairman Pai circulates the NPRM and Republicans push through Simington’s nomination in time for a vote, the effort will end there. Nothing prevents the Biden FCC from terminating the proceeding. Both Democratic FCC Commissioners have objected to a Section 230 rulemaking, as have several Democratic members of Congress. While it is unclear at the time of this writing whether the FCC will begin the Biden Administration with a 2-2 (or even 2-3) deadlock, or a 2-1 Democratic majority, sooner or later a Democratic majority on the FCC will terminate any proceeding that Pai could begin.

Barring some wildly unpredictable turn of events, it appears that Trump’s effort to regulate social media companies through the FCC will die with the end of his Administration.

Section 230 Reform from Congress Possible, But Unlikely in the Short Term

This year saw a fair number of legislative proposals to amend the scope of Section 230 liability protection. Most of these were simply vehicles by Republicans to voice their own displeasure at the perceived bias of social media companies, and linked Section 230 to “neutrality” in content moderation. Even if these bills reappear in the 117th Congress, they are unlikely to attract sufficient support to become law.

Two bills deserve particular attention as the most likely to move forward in the next Congress. Senator John Thune (R-SD) and Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI), prominent members of the Senate Commerce Committee, introduced the Platform Accountability and Consumer Transparency Act (PACT Act). Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), the Chair and Ranking member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, introduced the EARN IT Act. These bills take diametrically opposed approaches to modifying Section 230. The PACT Act requires interactive services to provide explanation for their content management policy, and requires the platform to provide an appeals process for users to challenge content moderation decisions. The PACT Act would also clarify that Section 230 does not apply to criminal content, and authorizes the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to enforce violations of the transparency and appeal policies.

The EARN IT Act takes a far more aggressive approach to content moderation. On the surface, the EARN IT Act conditions liability protection on taking necessary steps to control child sexual abuse material (CSAM). But it also creates a 19-member Committee charged with creating “best practices” for platforms that would create affirmative duties to actively police content for CSAM. This would fundamentally change the role of platforms by making them legally obligated to invest in capacity to police content and affirmatively report suspect behavior to authorities. Whatever the merits of this as policy, it substantially alters the legal liability regime governing social media services.

“It appears that Trump’s effort to regulate social media companies through the FCC will die with the end of his Administration.”

Commerce and Judiciary have competing claims to jurisdiction. It seems unlikely that substantive legislation can move forward until the committees come to some kind of agreement on approach. Although President-Elect Biden has stated that he thinks Section 230 should be repealed in its entirety, this seems extremely unlikely. Whether Biden will refine this approach over time and support some more plausible Section 230 reform remains to be seen. At the time of this writing, it does not appear that Biden regards the issue with anything close to the same urgency as Trump did.

Reform Through the Courts Is Ongoing

The proper interpretation of the scope of Section 230 has always been a matter for the courts. During the first decade or so of interpreting Section 230, courts took a broad view of Congress’ intent to immunize online services from liability for either third-party content (in accordance with Section 230(c)(1)) or for any manipulation of third-party content (under Section 230(c)(2)). More recently, as everyday business has increasingly moved online and digital platforms take up an ever larger portion of our economic and social interactions, courts have taken greater care to distinguish between hosting or editing content protected by Section 230 with business activity subject to standard rules of liability. The Ninth Circuit found that Section 230 does not protect websites that deal with renting or purchasing real estate from liability under the Fair Housing Act. The Third Circuit found Amazon liable under Pennsylvania’s retailer liability laws, because the sale of third-party products does not involve content under Section 230. Nor did Section 230 protect an online dating service from sending false profiles to entice people to re-subscribe.

Even without completely revisiting early Section 230 precedents as urged by Justice Thomas, this process of judicial interpretation will undoubtedly continue. We can expect courts to follow the same path as the Ninth Circuit and the Third Circuit in giving closer scrutiny to what conduct falls within the scope of Section 230 and what conduct does not. Justice Thomas’s recent call to completely revisit and narrow Section 230 precedent may not lead to courts below taking up this challenge explicitly, but it will no doubt encourage judges to take an increasingly narrow view of Section 230 immunity within the confines of these precedents.

Conclusion

It seems inevitable that the push by the FCC to redefine the scope of Section 230 through agency rulemaking will end with the end of the Trump Administration. But while President-elect Biden is unlikely to pursue Section 230 as a priority, his few public statements on Section 230 makes it clear he thinks the current law gives digital platforms far too much leeway to spread disinformation and defamatory content. Congress will continue to debate the issue of Section 230 reform, but until the jurisdictional committees can reach consensus on an approach, it seems unlikely that significant reform will pass. This does not mean that Section 230 will remain unchanged, however. The scope of Section 230 has always been a matter of judicial interpretation. This interpretation, in turn, has to some degree reflected the popular sentiment about online content. As society as a whole has grown less bedazzled by the concept of “cyberspace” and more concerned with the impact of digital platforms such as social media services, it seems most likely that future decisions interpreting Section 230 will narrow its applicability and attempt to inject greater nuance into its interpretation.