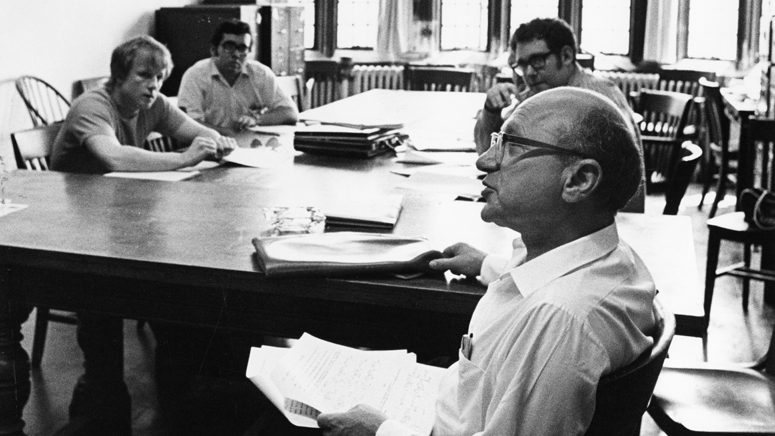

Milton Friedman had two inconsistent minds: That of an economist and an ideologue. The view that maximizing profits without constraint is a manager’s only responsibility is Friedman’s policy conclusion—but not his model.

Milton Friedman’s 1970 New York Times Magazine article The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits has shaped business education and practice for fifty years. A recent series in ProMarket revisited the article, with authors siding in favor or against it. While some defend Friedman’s conclusion that managers should care only about shareholders, others think managers should care about a broader set of stakeholders.

This persistent disagreement shouldn’t come as a surprise, so long as people take Friedman’s writing seriously. The reason lies in Friedman’s dual identity as an economist and an ideologue: Friedman the economist framed one plan of action and Friedman the ideologue implemented another. Or in the jargon of economics, he specified one problem for managers to optimize and then solved another. Those are the two—inconsistent—minds of Milton Friedman.

Friedman wrote that a corporate executive’s “responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with [the owners’] desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible….” That is the sentence that underlies Friedman’s policy conclusions and is the one people remember.

That sentence also accords with the way textbooks explain how firms operate. The “optimization problem” for managers to solve is to maximize profits subject to constraints imposed by available resources and technology. This textbook problem is otherwise unconstrained by any non-material considerations. Friedman’s phrase, in contrast, does not end as cited above. Rather, it ends with “…make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom [italics added].” In economics terms, Friedman wrote down an optimization problem that incorporated non-material constraints — the goal is profits, and the constraints are law and ethical custom. Unfortunately, he then derived his conclusions on shareholder primacy as if the optimization problem were unconstrained by such non-material considerations.

“To cite Friedman’s celebrated article and adopt the view that maximizing profits in an unconstrained way is a manager’s only responsibility is to cite his policy conclusion but not his model.”

Sticking with Friedman’s optimization problem, if an executive stands to make $1 billion by circumventing an ethical norm, then according to Friedman she should refrain from doing it, even though she has a responsibility to the company’s owners. Why? Because in Friedman’s specification, respect for ethical custom—however defined, as Friedman remains vague about what this means—takes precedence over profits. Yes, forgoing a dollar of profit when doing so will not compromise the law or ethical custom is, as he put it, “theft against the shareholder.” But when doing so compromises ethical custom, maximizing profits is not the rule: Stakeholders other than shareholders deserve consideration.

This leads to a useful definition of corporate social responsibility. Suppose there is a firm whose profits would be $1 billion by disregarding both law and ethical custom, $800 million by disregarding only ethical custom, and $600 million by abiding by both law and ethical custom. According to Friedman, the executive should choose $600 million. We can call the company that earns $800 million a law-abiding company, and a company that further abides by ethical custom (as mandated by Friedman) a socially responsible company. Corporate responsibility here is the morally driven exercise of profit restraint.

Though “ethical custom” can be a tricky term, in most societies it matches principles from two schools of thought in moral philosophy, both of which incorporate the interests of other stakeholders. The Utilitarian school defines the moral path as one where actions promote the well-being of society at large. The Kantian school defines the moral path as one where actions respect the autonomy of others.

While Friedman did not pause to analyze what ethical custom might mean, and did not explicitly link to any moral philosophy, his basic stance appears compatible with two central modes of ethical thought. He is animated by the idea that theft against the shareholder is wrong: This is presumably because theft is in general wrong, for reasons Utilitarians and Kantians have long noted – theft creates inefficiencies and violates individual autonomy. But if theft against the shareholder is wrong, as Friedman so compellingly argued, then by the same logic theft for the shareholder is also wrong. Theft for the shareholder is what happens when companies abuse their power, or deplete collectively owned resources, like clean air, clean water, animal species, or climate balance, without compensating owners.

Companies that refrain from such “theft” out of an ethical commitment are exercising a morally driven restraint on profit-making. They become socially responsible companies in a way that fits our definition, as derived from Friedman’s own optimization program.

To cite Friedman’s celebrated article and adopt the view that maximizing profits in an unconstrained way is a manager’s only responsibility is to cite his policy conclusion but not his model. The classic “shareholder versus stakeholder” debate does have a resolution: To be aligned with Friedman’s optimization program, stakeholders must be part of managers’ decisions so that firms internalize the wider consequences of their actions.