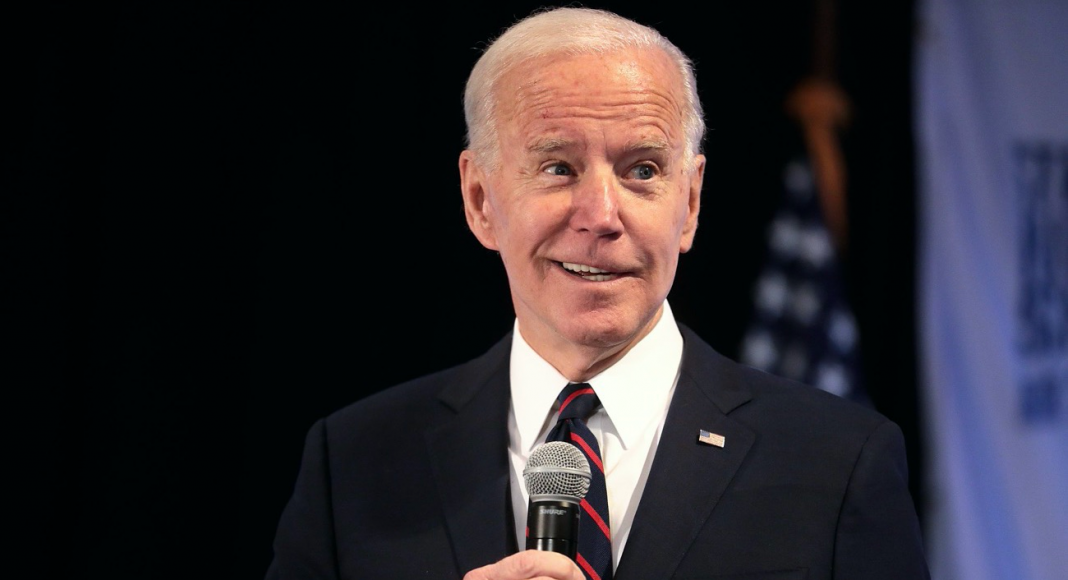

The Biden Administration can revive federal antimonopoly enforcement after 40 years of little action, even when faced with congressional opposition. Here’s how.

The new Biden administration will face countless tasks to repair America’s economy, distressed by decades of pro-monopoly policies and fragile supply chains strained by the Covid-19 pandemic. It will also likely encounter significant congressional resistance. Nevertheless, the new president and his administration should take at least three unilateral actions to start tackling America’s pervasive monopoly problem.

First, the Biden Administration should revive federal antimonopoly enforcement after 40 years of little action. In October, the Department of Justice (DOJ) filed its first significant monopolization case in twenty years against the search giant Google. The Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) widely expected lawsuit against Facebook will likely be the agency’s most important lawsuit in a generation. Building on the landmark 450-page House Antitrust Subcommittee report on Big Tech released last month, the Biden Administration can reverse the trend set by previous Democratic and Republican administrations and bring more antitrust cases by these federal agencies.

Second, President Biden should instruct the DOJ and FTC to publish new merger guidelines that follow a bright-line rules-based framework. Using bright-line rules would impose strict and precise limits on mergers and acquisitions, particularly for concentrated industries such as banking and technology that are at the center of the acquisition frenzy.

For more than a decade, the two federal agencies have anemically enforced American merger law and have failed to protect consumers from dangerous concentrations of corporate power. Substantial research has confirmed that the current merger framework, with its myopic and sole focus on prices, has failed by its own analytical benchmarks. Professor John Kwoka, in his landmark 2015 merger review study, found that one-third of mergers led to price increases of at least 5 percent. Additionally, the current version of the guidelines affords the agencies too much discretion and encourages subjective decision-making. The agencies’ merger guidelines can be easily changed and are offered significant deference by the federal courts.

The Biden Administration should use historical antitrust policy and practice in developing new merger guidelines and restrain continuing concentration across the American economy. In 1968, the DOJ announced bright-line merger guidelines that clearly explained when it would challenge a merger in court under the Clayton Act. The result was a vigorous merger enforcement landscape. However, lackluster merger enforcement since the 1980s has allowed countless industries to be controlled by only a handful of dominant corporations.

For example, since 2009, the four major Big Tech companies—Google, Apple, Amazon, and Facebook—alone have made over 400 acquisitions. Bright-line rules would reenact a vigorous merger enforcement framework that was consistent with Congressional intent. A bright-line rules framework would also adhere to reaffirmed Supreme Court precedent to disregard economic efficiency considerations that the agencies have incorporated into the current iteration of their merger guidelines.

“The Biden Administration should use historical antitrust policy and practice in developing new merger guidelines and restrain continuing concentration across the American economy.”

Lastly, the Biden Administration should instruct the FTC to enact bright-line rules prohibiting predatory and exclusionary practices. Specifically, the FTC should prohibit non-compete agreements and exclusionary contracts.

The FTC has broad rule-making authority to define and prohibit unfair or deceptive acts or practices and unfair methods of competition. The FTC can take advantage of this latent power to prohibit non-compete agreements and exclusive dealing agreements. These agreements are some of the most egregious and routinely used predatory business practices utilized by dominant corporations.

Non-compete agreements lock-in at least 36 million workers across every sector of the economy. Employers impose these restrictive agreements on workers in a take-it or leave-it manner. The agreements prohibit workers from obtaining a different job in a similar line of work. These contracts of adhesion thus bind a worker to their current employer.

Exclusive agreements alternatively require customers, distributors, and suppliers to solely engage with a dominant firm. These agreements entrench a monopolist’s power over consumers and suppliers by deterring and inhibiting the entry of potential rivals. The restrictive nature of these agreements also prevents firms from seeking alternative suppliers, suppressing competition between firms. In effect, these agreements tie weaker firms to a dominant corporation—creating a form of de facto vertical integration.

Substantial evidence, compiled by the Open Markets Institute [the author is an employee of Open Markets] and submitted in petitions to the FTC, confirms that non-compete and exclusionary agreements create a surfeit of harms. These agreements marginalize competitors, lower wages, inhibit the formation of new rivals, rest on dubious assumptions and evidence, and facilitate a marketplace ruled by predatory, exclusionary, and unfair business practices. The Biden Administration should instruct the FTC to use its broad rule-making power to ban both of these agreements.

There are many other antimonopoly policies the Biden Administration can and should implement, but these three would start to wholly reverse several decades of pro-monopoly policy by the federal government.