Latest US household survey findings reveal that the Covid-19 crisis caused a sharp reduction in Americans’ confidence in institutions—whether or not they were directly impacted by the pandemic.

The Covid-19 pandemic triggered one of the largest public health and economic crises the US has seen in recent history. To better understand how Americans are reacting to the crisis, we’ve been following the same representative sample of Americans through seven survey waves since April. The research is a joint partnership between the Poverty Lab, the Rustandy Center for Social Sector Innovation, and NORC at the University of Chicago, an independent, non-partisan research institution.

The latest results show that the crisis caused a sharp reduction in Americans’ confidence in institutions, regardless of whether they have been directly impacted by the pandemic. The crisis has also widened the pre-existing gap between Democrats and Republicans in their support for the role of government in the economy.

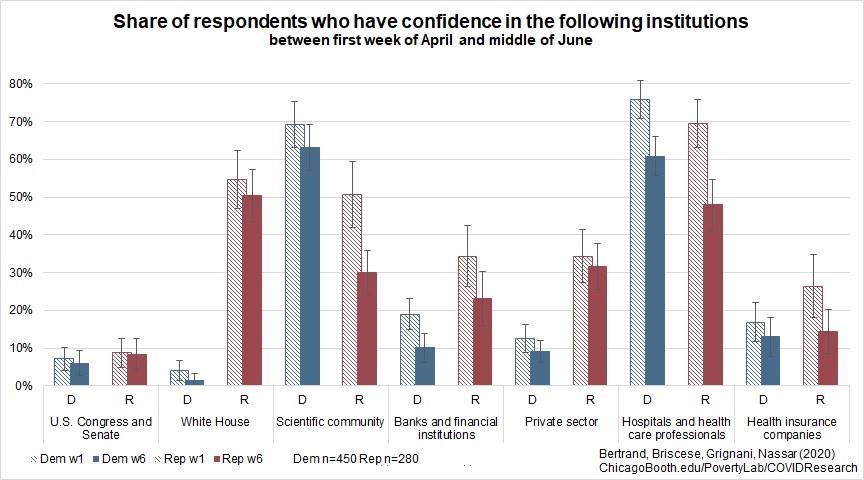

Between the beginning of April and the middle of June, the institutions that suffered the largest drop in trust are the scientific community (from 58 percent to 47 percent), as well as hospitals and health care professionals (from 70 percent to 50 percent). However, confidence in the scientific community diminished substantially more among Republicans, with a drop of over 20 percentage points (from a baseline of 51 percent). Among Democrats, one of the largest drop in confidence is in banks and financial institutions (from 19 percent to 10 percent), suggesting that Americans have been attentive to the actions taken in response to the pandemic by the people running these institutions.

A possible explanation for these variations in trust along party lines is the fact that some institutions, such as the scientific community, have been politicized since the first months of the pandemic. This is supported by our econometric analyses, where we see that among Republicans, those who consume partisan news sources are significantly more likely to have decreased their confidence in the scientific community (from an initial support of 50 percent to 20 percent) compared to those who consume less biased media (56 percent to 41 percent).

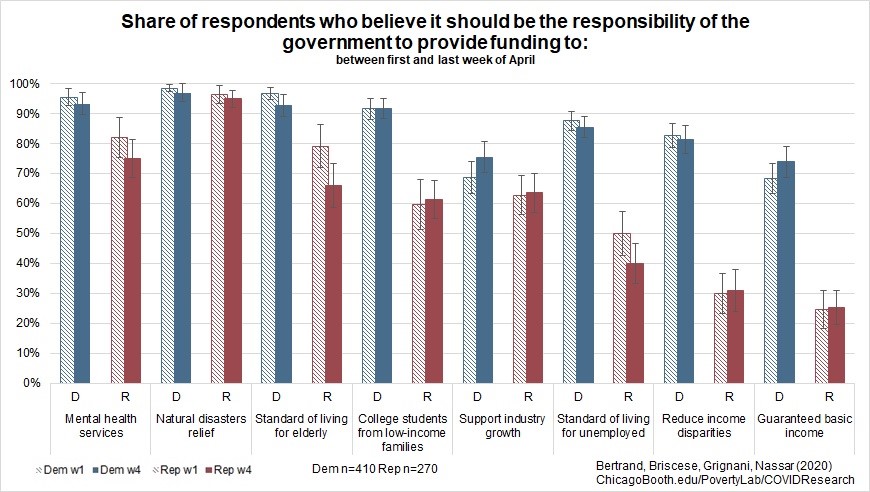

We have also been tracking preferences for government intervention across a broad range of policy areas, and find that between the first and last week of April, Democrats increased their support for policies like guaranteed basic income (from 68 percent to 75 percent) and support for industry (from 68 percent to 74 percent). Among Republicans, the largest change has been a decrease in support for providing a standard of living to the elderly and the unemployed (from 79 percent to 66 percent, and from 50 percent to 40 percent, respectively).

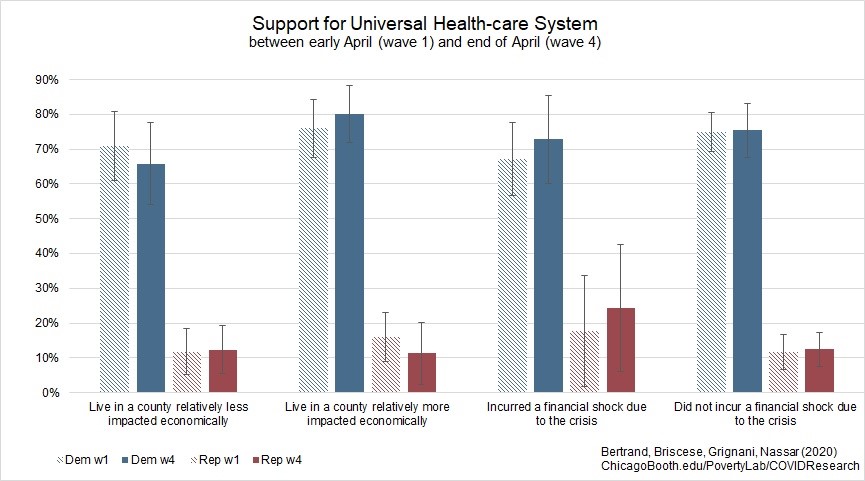

In our analyses we identify two main types of shocks—health and financial—and whether these shocks have been affecting respondents directly or indirectly between the beginning and the end of April. In the financial domain, we found that respondents who incurred a financial shock are more likely to have increased their support for a universal health-care system, regardless of the political party, although not in a statistically significant way. Living in an area that was more economically affected increased support among Democrats but not among Republicans.

In the health domain, we asked whether respondents personally knew anyone who was hospitalized with Covid-19 (roughly 20 percent of our sample), and also tracked the Covid-19 death rate per thousands of inhabitants in their county of residence as a measure of indirect shock. Health shocks, whether direct or indirect, seem to play an even less important role in changing people’s views on the introduction of a universal health-care system in the US compared to respondents’ political ideology. (Graphs on the role of health shocks are available here).

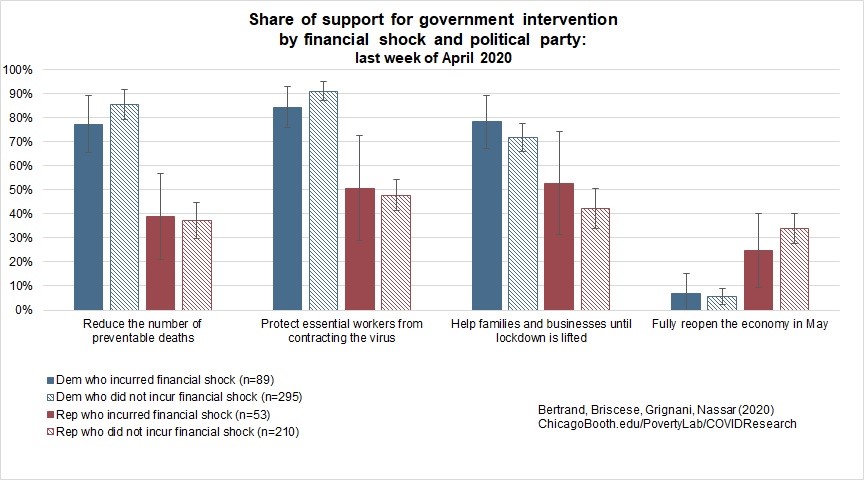

When asked about government spending on programs to counteract the negative shocks caused by Covid-19, political affiliation remains a strong predictor for support or opposition, although it seems less polarizing than for long-term government policies like welfare programs. For instance, in the last week of April, 85 percent of Democrats and 40 percent of the Republicans believed that it was a government’s responsibility to provide for the unemployed, compared to the share of those who supported spending to help families and businesses during the lockdown (72 percent for the Democrats and 47 percent for the Republicans).

If policy preferences were driven by self-interest, we would expect individuals hit by the crisis to be more in favor of public spending regardless of their political affiliation. Instead, we find that party remains the strongest predictor for support also for coronavirus-related policies, while personal experiences do not play an important role. (Graphs on the role of health shocks are available here).

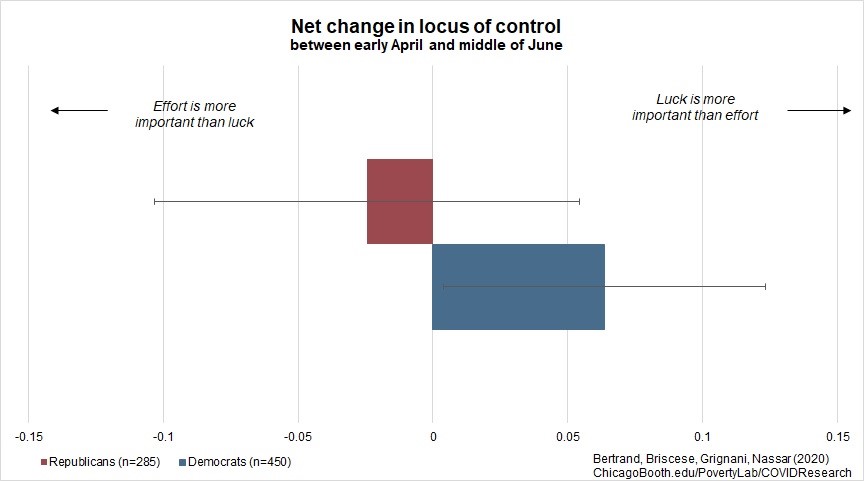

Previous studies indicated that preferences for redistributive policies are partly influenced by whether a person’s locus of control can be considered as “external” or “internal”—that is, whether a person believes that success in life depends more on luck than hard work. This measure was first suggested by the psychologist Rotter (1954) and has been used extensively in the social sciences, including in the study of political identity (Sweetser, 2014).

We asked respondents whether they believed that success in life is mainly due to luck, efforts, or both. Over a period of just 10 weeks, we found that Democrats and Independents decreased their internal locus of control, which is correlated with support for redistributive policies, whereas the opposite is true among Republicans. While at the beginning of the crisis, 45 percent of Democrats believed that success was due to hard work, that share decreased to 41 percent by the middle of June, compared to 71 percent and 73 percent of Republicans. In a series of regression analyses, we find that having undergone a financial setback, and residing in a county that has witnessed a large increment in deaths significantly increased the chances of shifting toward believing that luck plays a larger role in influencing success in life.

We’ll continue tracking changes in beliefs and support for policies in the final wave of the survey, unpacking some of these results, and posting the latest findings here.

Note: The survey was administered using a sample drawn from NORC’s probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel, which is designed to be representative of the US population.