In an interview with ProMarket, Barry Lynn discusses the current state of American antimonopoly, what the Covid-19 crisis has taught us about the fragility of our industrial system, and why he believes that monopoly power presents “the gravest domestic threat since the Civil War.”

Wherever you look these days, it seems that people are talking about monopoly power. The House Judiciary Committee released its long-awaited report on digital platforms last week, and Republican Members have published their own report which—though much more reserved than the Democratic-led committee’s report—still supports many of its findings and recommendations. As the most divisive election in over a century highlights Google’s and Facebook’s role in the spread of misinformation, Big Tech finds itself in the crosshairs of both Democrats and Republicans.

Meanwhile, the US’s failure to contain the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the role that concentrated supply chains play in America’s dysfunctional health care system, and the literature on the economic impact of concentration and market power keeps growing, all serving to form a cohesive narrative that ties monopoly power to many—if not most—of the ills plaguing the American economy and society today.

Not even five years ago, most of this would have been unthinkable. Facebook was still thought of as a democratizing force, Jeff Bezos hailed as the savior of journalism, and Google was a mainstay of the White House. Antitrust, to the extent that it was thought of beyond a small group of economists and lawyers, was considered a relic of a long-gone era.

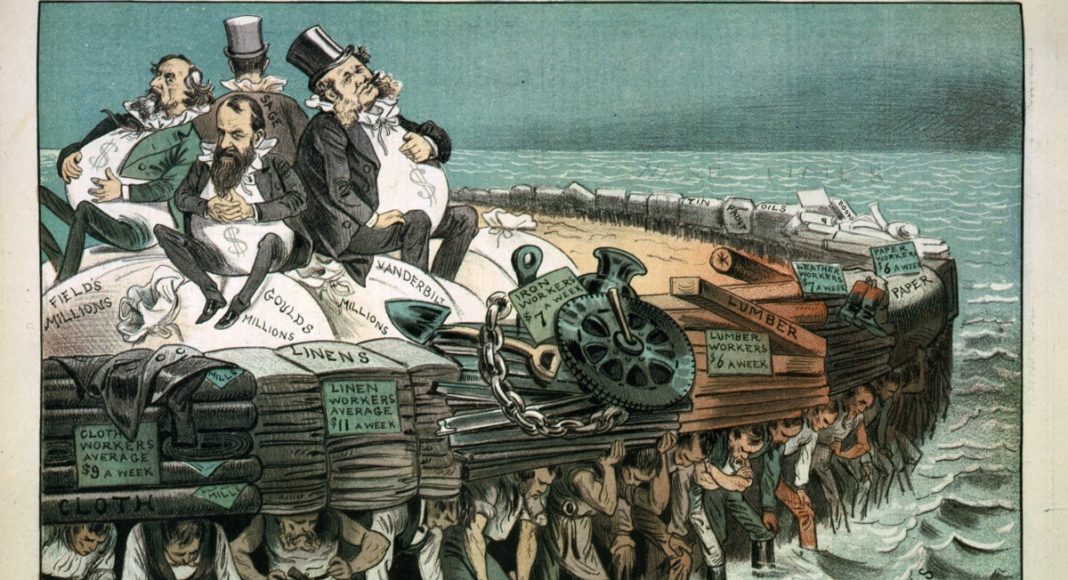

One of the key figures leading the remarkable resurgence of American antitrust in recent years is Barry Lynn, founder and executive director of the Open Markets Institute. Lynn’s work, particularly his influential 2010 book Cornered: The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of Destruction and the group of researchers he gathered over the years, first at the New America Foundation and then (after Lynn and his colleagues were booted from New America due to their criticism of Google) at Open Markets, have played a crucial role in driving the fledgling antimonopoly movement.

Last month, Lynn published Liberty from All Masters: The New American Autocracy vs. the Will of the People. For Lynn, the book is the culmination of a 20-year investigation into the effects of monopoly power and the final part of a trilogy that began in 2005 with End of the Line: The Rise and Coming Fall of the Global Corporation, a book that served as a stark warning of the risks that a highly-concentrated global industrial system could pose. Largely completed before the eruption of Covid-19, Liberty from All Masters is being published after many of Lynn’s warnings came true. Citing Louis Brandeis and W.E.B. Du Bois as its main inspirations, the book is a thoroughly-researched history documenting the danger that monopoly power poses to democracy and to civil liberties.

In a recent interview with ProMarket ahead of the Stigler Center’s Should Antitrust Promote Economic Liberty? event, we asked Lynn about the current state of American antimonopoly, what the Covid-19 crisis has taught us about the fragility of our industrial system, and his argument that monopoly power presents “the gravest domestic threat since the Civil War.”

[This conversation has been edited and condensed for length and clarity]

Q: Last week, the House Judiciary came out with a very aggressive report on digital platforms calling for the strengthening of antitrust laws, tightening enforcement, even break-ups in some cases. How likely do you think it is that at least some of these recommendations will be embraced by the next administration?

This was a transformative event in the fight against monopoly in the United States and the most important investigation of private monopolies in the US since the Pujo Committee in 1913, which broke the power of the money trust. Chairman Cicilline and the committee provided us with a true blueprint for action to ensure that the internet economy can be made safe for democracy in the 21st century and for American capitalism.

The extent of the research and the sophistication of the analysis, and the fact this is going to have a lot of bipartisan support, is going to make it very difficult for the Biden administration to run counter to any of the major recommendations of this committee, should Biden be elected.

We have to keep in mind that 50 states, plus DC and Puerto Rico, have opened investigations and are preparing to act against Google. Almost all of these states and territories are investigating Facebook. This is a popular uprising that we’re seeing. No matter what the central actors in a Biden administration may want to do, they will find it extremely difficult not to act largely according to these recommendations.

Q: The House report follows years of renewed interest in antitrust policy. I think more than anyone else, you have been the progenitor of the growing US antimonopoly movement. What do you make of its state today?

It’s a great question. Too often, we end up focusing only on what’s bad—and it’s really bad out there right now, in terms of concentration of power and control. But what’s different is that when Cornered came out in 2010, no one was paying attention to corporate concentration at all.

Today, we’re in a fantastically different place. Even compared to four years ago, we’re in a fantastically different place, because we now have many politicians who understand this problem and what to do about it. We also have a growing array of smart political economists and enforcement agencies much more focused on these issues.

There is also a growing number of grassroots groups that have made the issue of monopoly fundamental to their work. Both at the level of understanding the problem and organizing to deal with it, we are in a fantastically better position than when we started these efforts more than a decade ago.

“The problem with the experts is they’ve been trained to see the world in certain ways that hide corporate power.”

Q: You’ve been studying the effects of concentration on the stability of our supply chains for over 20 years. In one piece, you even asked your readers to consider what would happen in the event of a flu epidemic that could disrupt the basic systems that we all depend on. Then, of course, it happened in real life. What would you say the Covid crisis and all the disruption that it caused has taught you, as someone who’s been warning about this since 1999?

What I’ve seen is that even after Covid demonstrated the terrifying fragility of many industrial systems, many people remain shockingly immune to the facts.

Many of our economic experts have demonstrated a truly remarkable ability to ignore the source of the disruptions —which is the concentration of power and control over essential industrial activities, and the destruction of industrial capacity by the monopolists.

An N95 mask, wholesale, probably costs no more than a dime a pop. We can produce more than enough wrappers and boxes for our hamburgers—so why is it that we can’t produce enough N95 masks so that every doctor, every nurse, every train conductor, every bus driver, every person in a grocery store, can put on a new clean mask every day? We have the money, we have the know-how. Yet here we are, more than six months into the crisis, and we haven’t done a damn thing, really, to fix the underlying source of the problem. Which in this specific case that a powerful monopolist—3M—governs the distribution of masks in America in ways designed to protect its margins, and not the public’s health.

Regular folks, I think, understand this really well. They understand that you don’t put all your eggs in one basket. They look around and say, “We need to have a system that ensures that we have the drugs that we need when we need them. We need to have a system structured so that we get the masks and the PPE that we need when we need them.”

So, in sum, what Covid has demonstrated to me is that many of the “experts” are even more obtuse than I had dared to imagine.

Q: How do you explain this?

The problem with the experts is they’ve been trained to see the world in certain ways that hide corporate power.

It’s easy to understand why there have been all these shortages, and all these near cascading supply chain crashes. Monopolists grab hold of machines and services that we need, then restrict access to them, build walls around them, so they can charge more for less. Concentration of power leads to concentration of capacity, which leads to disruption of resiliency, to the stripping away of capacity, to the engineering of shortages. That’s always been the way it works. But many of our economic “experts” have been trained to not see that.

In Liberty from All Masters, I spend a lot of time discussing the blindness of economists. An example I give of someone who knows there is a big problem with economics, but who doesn’t really have the ability to understand what the economists don’t see, is Thomas Piketty. In writing about inequality in Capital [in the Twenty–First Century], Piketty speculates that it probably has to do with concentration of power. But then he punts and says “I’m not a political economist. I have no idea how to even begin to understand the actual effects of concentrated power, but I suspect that that’s where the answer lies.”

Piketty attacks American economists for generally being even less able to see the actual structures of the real world than he is, which I generally agree with. But what does Piketty do in his new book? He drives right past the question he teed up in Capital. He starts opining about the history of this ideology and that ideology and fills a thousand pages with a theory of the world that in the end takes us no closer to any practical solution to any of our problems. And he’s one of the good ones.

Q: Your book is coming out at a time when the challenge of a once-in-a-generation pandemic is compounded by political chaos fueled by misinformation on social media platforms. In the book, you write that Americans today face “the gravest domestic threat since the Civil War.” What is the nature of that threat?

My point here is simple. Google, Facebook, and Amazon have concentrated so much power and control over so many aspects of our lives, and have built business models that lead them to manipulate how we communicate and do business with one another. The result is an immediate, direct threat to our personal liberties and, indeed, a direct threat to our democracy.

I mean, just think about fact that these corporations have the power to manipulate the flow of news and ideas and information between the reporter and the voter, between the author and the reader. That alone is a phenomenally dangerous power.

And the threat is not only political in nature. The way these corporations manipulate information and commerce also increasingly disrupts our ability to process information and to make sense of the world. When you have a few monopolies that control so much information, and can set personalized prices for each seller and each buyer, the entire pricing system breaks down. When all prices are essentially arbitrary, we are left with nonsense.

Q: The capitalism that Adam Smith wrote about was based on an assumption that market prices are clear. With Big Tech platforms today, though, we have no idea what prices are. We have no ability to process that information and make rational decisions.

Absolutely. This is another indictment of so much of the economics profession today. Most economists keep pretending that we are still in a Smithian world.

I haven’t seen any economist really try yet to make sense of this collapse of the pricing system, of what it means for our ability to govern our lives and our society. For a creative economist, this is actually a wonderful moment. You could make a career for yourself by just going in and looking at the actual facts.

Q: Many Americans fear that their democracy is in danger at the moment. In the book, you address this fear, but you argue that it isn’t Donald Trump, or tribalism, or the loss of faith in liberal democracy. These are all symptoms, you write, of the real problem, which is monopoly and concentration of power. How is concentration driving all this?

Whatever sector of the political economy you look at—health care, hospitals, pharmaceuticals, retail, food, farming—concentration is a fundamental problem. You see monopolists distorting outcomes in ways that entirely affect both the citizen as producer in that sector and also the citizen as a buyer of those goods or services.

Massive inequality, that’s a direct function of monopolization. Yes, inequality is also a function of the way Wall Street is regulated, and the way the Federal Reserve bails out certain people and doesn’t bail out others. But those decisions are second-level decisions. The primary problem is that power is so concentrated that some people walk off with all the profits and others are steadily stripped of their assets year after year.

Then there is the concentration of opportunity, in the hands of fewer and fewer people. America was built to enable almost any person to start a business or start a farm, or flip off the boss and go get a new job. But every day folks find their lives more constrained, their freedom to start businesses and move around even more.

People are smart. They understand that this concentration of power and opportunity is fast destroying their ability to make good lives for themselves and their families. They understand that it is undermining our ability to engage in constructive political dialog. But then they turn to the experts, who generally say that all is well. Yes, there are many really smart economists who understand this, and more every day. But as a group, this profession continues to hide the fundamental problem. And so folks get angry, and confused, and lash out in destructive ways.

Q: In the book, you draw a direct line between the potential rise of autocracy in America and the neoliberal revolution of the 1980s and 1990s, especially the undoing of antimonopoly laws. What is the connection between the two?

Neoliberalism was designed to undermine the entire system of antimonopoly laws developed since the founding of the nation. Neoliberalism was designed to replace democratic control over political economic regulation with private, corporate control, with little-to-no public input. That’s what it was designed to do.

The monopolization that resulted came in two stages. Stage one began after the Reagan revolution of the ‘80s and the application of neoliberal ideas to antitrust. Then Bill Clinton took these ideas and applied them to the trading system. That’s what we saw with the World Trade Organization, with the Uruguay Round of GATT.

Then the Clinton people went into individual areas of the US political economy where there were other regulatory mechanisms—the defense industrial system, the energy system, the telecommunications system, the banking system, the commodities trading system—and subverted the democratic systems of regulation in each of these individual systems.

This was not partisan in any way. The Reagan folks started the neoliberal revolution and the Clinton people finished it. Taken as a whole, the changes made during these two administrations brought us the age of Walmart, Citibank, Goldman Sachs, ExxonMobil, Boeing, News Corp—with these super giants controlling entire realms of the political economy.

By ten years ago or so, we had clearly entered stage two in this concentration. This second stage has been driven by corporations that are fundamentally digital in nature, that rose to power online: especially Google, Facebook, and Amazon. Their digital nature has enabled these corporations to grew and concentrate power much more swiftly, to the point where they’re increasingly exercising control over the super-large corporations of the last generation. I mean, Google and Facebook today can exercise a certain degree of control over News Corp and can even make someone as powerful as Rupert Murdoch afraid.

The first 20 years of the Reagan revolution led to massive concentration of power in the hands of a few hundred bosses. In the last 10 years, we’ve seen a pyramiding of that power, to a point where the bosses of stage one now have bosses. So today, rather than having 500 bosses running our political economy, we’ve got three.

And just to complicate matters, these new corporations have powers that the previous corporations could not even begin to imagine, thanks to their ability to track, gather, store, and manipulate information about other people’s lives and businesses.

“The ideology that has governed most economic thinking in America for more than a generation is collapsing, suddenly.”

Q: You said the experts are “hiding the problem.” Do you think this is deliberate, or simply that they don’t see it?

It’s kind of a late Soviet moment. American economics right now is like Soviet economics in 1987. More and more economists understand that the entire intellectual system they created is a lie. They just don’t know what to do about it.

But the day of reckoning is here. With ever more people who actually realize that the system is intellectually corrupt, every economist is faced with a clear choice: either break away from the world they have lived in for so long, or defend what they know to be a lie.

For a lot of people, it’s extremely disturbing to admit that you’ve been duped, to admit that your career has been in the service of bad people and bad outcomes. That’s hard. But neoliberal economics is collapsing, and the smart economists are beginning to jump ship really fast. It will be interesting to see who can leap into the next era, and who sinks.

Q: You called it a “late Soviet moment.” Can you elaborate on what you mean by that?

I was in my 20s during Glasnost and the collapse of Communism in Europe. Much of that time I was covering a Maoist guerrilla movement in Peru, as a reporter. So I paid very close attention to the philosophical debates in economics during those years.

In the Soviet Union, what we saw was the sudden collapse of belief in a particular ideology. Every Soviet economist had believed the ideology when they were young. But there came a moment when they realized the system was failing, in most key respects. This eventually forced them to see that the ideology itself was bogus. By 1987, pretty much every Soviet economist did.

Are there any schools of Soviet economics anymore? No. Were there any kinds of schools of Soviet economics in 1992? No. Every Soviet economist in 1987 was still studying Soviet economics, even if they didn’t believe it. By 1992, nobody was. It was over.

Today we face such a moment here in America. The ideology that has governed most economic thinking in America for more than a generation is collapsing, suddenly. Even the massive wealth of Mr. Koch and all the power of the apparatus his team and his fellow autocrats have built to promote neoliberal thought, won’t be able to prop up the neoliberal lie. The revolution is here. The only question is who will ride this wave, and who will drown.

Q: There’s a growing reckoning in recent years with how much the antimonopoly coalition of the previous century had to do with the alliance between New Dealers and Southern segregationists. How can antimonopolists today build a coalition without repeating the mistakes of the past?

The idea that the antimonopolism of the last century was based on racism is simplistic and dangerous. It’s an idea that is designed to hide our own power and our own capacities from us.

Certainly, until the civil rights victories of the ’60s, America was not a true democracy. And certainly, the Democratic Party, which was the main vehicle citizens used to establish the new system of industrial liberty in the 20th century, was deeply corrupted by racist Jim Crow structures in the South and the racist structures in the North.

But we have to separate the fight against antimonopolism from racism and understand that the antimonopoly achievements of the 20th Century didn’t depend on racism—if anything, it was the opposite.

As an example, look at Thurgood Marshall. Thurgood Marshall was a fantastic lawyer who traveled around the US fighting Jim Crow, fighting lynch laws, and devising an incredibly sophisticated legal strategy for breaking down the entire system of segregation, piece by piece.

Marshall, when he became the first Black justice on the Supreme Court, ended up being the last of the great defenders on the Court of the American antimonopoly tradition. Why was that? Because Marshall understood that when folks marched from Selma to Birmingham, the only place they could sleep at night was on the fields of an independent black farmer who owned his own land. And Marshall knew that all of the work that the NAACP and so many other groups had done over the years to break segregation had been largely funded by independent Black-owned businesses.

Marshall understood that monopolization ends up putting every American under the more or less direct control of white-dominated power structures. He understood that having that small business and small farm infrastructure was fundamental to the civil rights movement and to the achievement of true democracy in America.

Q: One thing that surprised me about the book, and in this conversation too, is that despite the grimness of the current political moment, you are surprisingly optimistic. You describe this as a time of peril but also one of opportunity.

Right now, we have the greatest opportunity that human beings have had since the Second World War and perhaps in more than 100 years —to actually build a world in which we have a democratic political economy that works for the individual, for the community, and for the wellbeing of world itself.

That’s because we are in the process of waking up from this fantastic lie, the neoliberal lie. Neoliberalism is a form of darkness, of ignorance. For a generation, we have believed in fake Gods. Now we’re waking to the fact that these Gods don’t exist. The overthrow of neoliberalism is the opportunity for us to once again enlighten ourselves about the true nature of the world and to all of the power that is in our own hands.

Q: This may be true for the intellectual debate, but when we look at the state of the political economy right now, it seems as though the opposite is happening: Shaoul Sussman and others have argued that Amazon and other tech monopolies are well-positioned to come out of this pandemic more powerful than ever.

I have confidence that the American people, given a clear choice between living a life of servility, chaos, and collapse, under the rule of a few bad boys in Silicon Valley and on Wall Street, and life as free, self-governing citizens in a prosperous and safe world, will choose the latter.

Yeah, Amazon is getting richer by the moment. But there’s a limit to how many people Jeff Bezos can buy.

The only thing that will ensure the victory of Google, Facebook, and Amazon is our own despair and hopelessness. That is really their only weapon. The time has come to look beyond the monopolists themselves, and the dangers they pose, to the world we will build after they are destroyed. True democracy, true liberty, true sustainability, they are all ours to have, if we will stand up and make them.