As the race to find a Covid-19 vaccine or treatment rages on, many have raised concerns over trustworthiness of clinical research and questioned whether investigators have a conflict of interest that undermines their integrity. A new study analyzed trial results reported to the ClinicalTrials.gov registry and finds overall reassuring evidence for the integrity of clinical research. The authors also identify certain subtle patterns that regulators should keep an eye on when it comes to the evaluation of Covid-19 trials sponsored by smaller companies.

The Covid-19 pandemic is disrupting people’s way of life all around the world. A safe and effective treatment, or even better, a vaccine, would be a gamechanger. There are many promising candidates in development, but before they can be approved for widespread use, safety and efficacy need to be demonstrated in clinical trials, just like for any other newly developed drug.

By October 3, 2020, 3,507 studies related to Covid-19 were registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, the largest registry for clinical trials. It’s not only the big pharmaceutical companies who are involved in the race for the first big breakthrough. Many smaller and less famous biotech enterprises have thrown their hat in the ring as well.

Clinical research involving human volunteers should be held to highest ethical standard at all times, but in the light of the current global emergency, the integrity of these clinical studies is arguably more crucial than ever. Just imagine that a vaccine that does more harm than good is approved prematurely and distributed to billions of people.

We often hear allegations that pharmaceutical researchers are subject to major financial conflicts of interests. Massive research and development costs and the lure of potential large profits in case of success might push investigators to withhold unfavorable results or beautify data. The “winner of the vaccine race” will strike gold given the world-wide demand. This outlook is why many companies take large risks with very high up-front investments, which may be lost if their attempts are not successful—or even if they succeed, are not fast enough to be among the first. On top of this financial pressure, there is the additional pressure from the public demanding the panacea that allows everyone to get back to their normal lives.

“The ‘winner of the vaccine race’ will strike gold given the world-wide demand. This outlook is why many companies take large risks with very high up-front investments, which may be lost if their attempts are not successful—or even if they succeed, are not fast enough to be among the first.”

In a study recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), we systematically analyzed results of pre-approval (phase II and phase III) drug trials reported to ClinicalTrials.gov until August 2019, in the time before the pandemic. Overall, our results are reassuring for the integrity of registered clinical trials and give reason for hope that the we can also trust the results of Covid-19 trials.

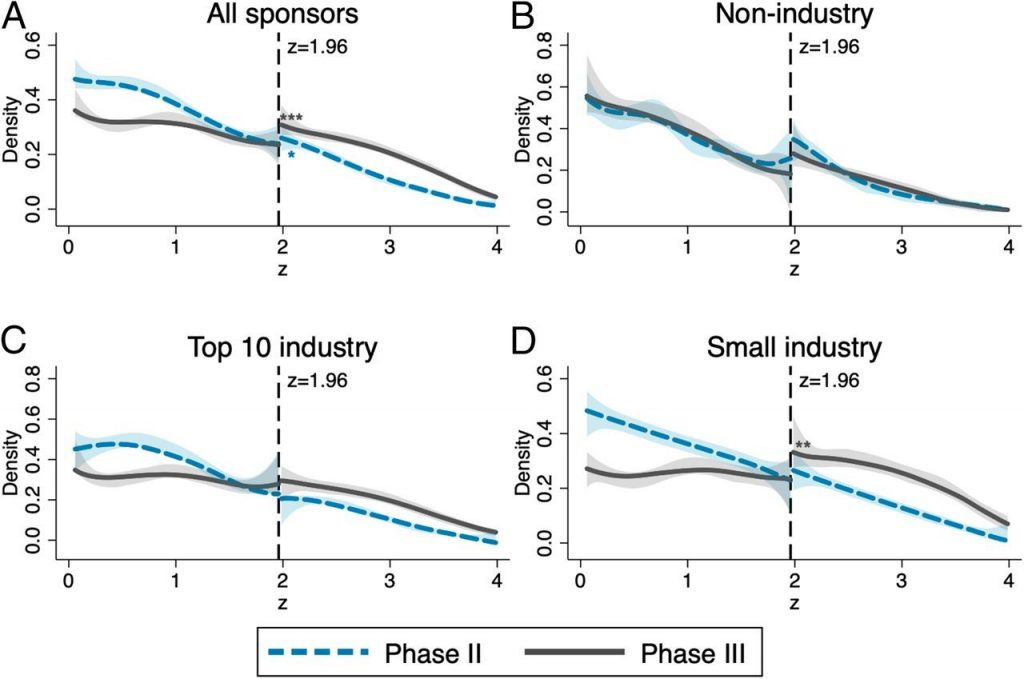

Our analysis focuses on the distribution of z-scores, a statistical measure that is isomorphic to p-values, comparable for all trials and plays an important role in the evaluation by drug regulators. As shown in Figure 1, we do not find an artificial spike of z-scores right above 1.96, the salient threshold for statistical significance at the 5 percent level. This threshold is often used as the first point of reference for the evaluation of the strength of statistical evidence.

Previous studies of publications in academic journals across a number of disciplines (including economics) identified bunching of results right above this threshold, which is commonly interpreted as evidence for manipulation of results to clear this hurdle (“p-hacking”). This does not seem to happen in phase II and phase III trials that report to ClinicalTrials.gov; neither in trials by non-industry sponsors (panel B), nor in trials conducted by the ten largest pharmaceutical companies ranked by revenue (panel C) or the remaining smaller industry sponsors (panel D).

However, a deeper look uncovers some suspicious regularities. For phase III trials by small industry sponsors (panel D), we found a persistent upward shift of the density of z-scores at the significance threshold. Though not as alarming as a spike right above this threshold, this break suggests that some less favorable results are not reported to the registry, something that is not supposed to happen. Negative results also contain valuable information. They prevent other researchers from replicating the efforts, wasting time and money, and putting more human volunteers at risk.

Another subtle pattern we find is the large increase in the share of significant results from phase II to phase III for all industry sponsored trials (panel C and D). To some extent, this progression is to be expected, because only the promising phase II trials are continued into phase III. Selective continuation makes sense for profit-maximizing firms that are willing to invest in further research only if the chances for eventual approval are high enough. This pattern is reasonable also from an ethical point of view because human volunteers should not be put at risk if no benefits are expected.

But can selective continuation of only the more promising phase II trials fully explain the increased number of statistically significant results in phase III? To answer this question, we linked phase II and phase III trials in the registry and estimated the continuation probability of a phase II trial conditional on the z-score and other observable trial characteristics. This method allowed us to predict a phase III distribution, which we then compared to the distribution of actually reported phase III results.

For trials sponsored by large pharmaceutical companies, the predicted share of significant phase III results and the actual share align nicely. Smaller industry sponsors, instead, report a higher share of significant results in phase III even though they are less likely to terminate a drug investigation with phase II results under threshold. While we cannot provide a definite answer for the reason for this discrepancy, one possibility is that small companies are selective in reporting only more favorable phase III results to the registry.

What drives the difference in reporting discipline between big pharma and smaller firms? More research is needed to answer this question. A possible interpretation is that reputational concerns and the resulting economic incentives play an important role also in the pharmaceutical industry, as has been documented in a number of other sectors.

Even though Food and Drug Administration (FDA) legislation mandates disclosure for a large number of trials and includes fines for non-compliance, to our knowledge these rules have never really been enforced. In recent years, public awareness of transparency concerns in clinical research has increased, motivating many large companies to establish internal disclosure policies and take reporting of results more seriously. However, reputational concerns might have less disciplining power for smaller companies. Stricter enforcement of fines may be necessary to incentivize smaller companies and public research institutions to comply with disclosure rules.

Given the benefits of having all trial results publicly available, our findings suggest that regulators should pay particular attention to enforce transparency of trials sponsored by smaller companies. This insight may also be valuable for the evaluation of Covid-19 trials—research by smaller sponsors might benefit from closer regulatory oversight.

The ex-post benefits for society of transparency in clinical research and publicly accessible trial registries containing ALL results are undeniable. However, economic theory also suggests that that mandatory full disclosure of all results is not always the best policy once we take into account the ex-ante incentives of investigators to invest in costly research. Strict enforcement might chill incentives to engage in costly but socially desirable R&D activities in the first place. An important question for future research is whether this chilling argument holds water also in the data.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this piece first appeared in VoxEU.org.