A new study looks into the social costs associated with private prisons to show that privatization may come with social trade-offs when governments fail to write complete contracts. However, the study finds that social trade-offs are partially mitigated by the monitoring role of institutional investors, highlighting the importance of institutional investors in corporate social responsibility outcomes.

Editor’s note: To mark the 50-year anniversary of Milton Friedman’s influential NYT piece on the social responsibility of business, we are launching a series of articles on the shareholder-stakeholder debate. Read previous installments here.

Privatization has been a popular policy tool among legislators around the globe. Starting in the 1980s, with the Reagan administration’s motto “don’t just stand there, undo something,” the United States government has been heavily relying on outsourcing government services to private enterprises, especially in sectors like the prison industry.

With the expansion of the War on Drugs under Reagan, the US observed nearly a 50 percent increase in incarceration rates between 1980 and 1985. This sudden spike in incarceration rates gave further incentive to the US government to outsource prison services to the private sector. Although privatization of prison services has been a popular policy tool in the 1980s and 1990s, there has still been an increasing reliance on private prisons. For instance, although the total number of prisoners rose by only 10 percent between 2000 and 2016, the number of inmates in private prisons increased by 47 percent, whereas the number of inmates in private immigration detention centers rose by 442 percent.

Was the decision of the government to rely so heavily on the private sector to incarcerate and rehabilitate criminals been a good choice, from a social welfare perspective? Alternatively, did privatization come with a cost to society, given that private prison management companies may have an incentive to only care about profits?

Privatization advocates argue that private enterprises may provide services in a more efficient way than the government does. Yet previous academic studies, such as a seminal 1997 Quarterly Journal of Economics paper by Oliver Hart, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny, raise a serious theoretical concern that privatization may come with trade-offs that society has to pay for.

In particular, when the government fails to specify what needs to be done in every possible incident in the contract it signs with a private enterprise (i.e., the contract is “incomplete”), owners of the private company have the residual right to make decisions on the non-contracted dimensions that may be optimal from a profit maximization point of view, but may be socially suboptimal.

In other words, when the government leaves gaps in the contract with the private company that manages prisons, the ultimate decision goes to the owners of the prison management company who need to decide on whether to solely maximize profits or to consider social consequences of not providing adequate rehabilitation services in prisons. Considering the fact that there has been a nearly 60 percent increase of institutional ownership in public companies that manage prisons between 2000 to 2016, one may wonder whether institutional investors internalize the social consequences of prison privatization.

Institutional investors around the globe have been vocal in calling out CEOs of portfolio firms to take societal concerns into account when making managerial decisions. For instance, in his past three annual letters to CEOs, Larry Fink of BlackRock, the largest asset management company in the world, has sent a strong message that companies need to have a positive contribution to society, or else they will lose the support of BlackRock. Do such efforts by institutional investors, however, translate into improvements that ultimately benefit society?

To tackle the question on whether institutional investors may offset the social costs that arise as a result of outsourcing government services to private enterprises, I have compiled a novel dataset on almost 1,500 state prisons after filing 51 state-specific (including Washington, DC) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests and hand-collected data from thousands of government documents.

Consistent with theoretical predictions of prior studies, I find statistically significant evidence that prison privatization is associated with an increase of inmate suicides by up to 40 percent. These results are robust to controlling for 27 time-varying prison-level factors that may impact the ex-ante likelihood of committing suicide or unobserved changes that take place at the state, year, or prison levels.

To examine why there is a high number of suicides, unexpected deaths, and total deaths in private prisons compared to public prisons, I also examined whether there were fewer resources provided in private prisons. I do find strong statistical evidence that the high association between privatization and mortality rates is possibly due to the fact that there are fewer educational, social, and overall rehabilitation programs offered in private prisons. However, these results do not examine whether different investor types may matter when examining the social costs that arise as a result of privatization.

As theory predicts, when government contracts are incomplete (i.e., not everything is written in the contracts), residual decision rights may play an important role in examining the social costs that arise as a result of prison privatization. In particular, what is the role of institutional investors when the government does not write a complete contract and public companies that manage private prisons sacrifice quality to be more profitable? As Oliver Hart and Luigi Zingales predict in their 2017 paper, shareholders may “take social factors into account and internalize externalities,” which may include social costs.

Institutional investors have the ability to use their voice when such social costs arise and may offset such negative social externalities. I find consistent evidence that for a 1 percent increase of total institutional ownership in public companies that manage private prisons, there is a reduction of 1.2 percent in prisoner suicides. These magnitudes are economically significant considering the fact that there was an increase of over 30 percent in institutional ownership levels since 2013.

However, given that institutional investors have different preferences, I further examine whether investors with different investment strategies and holding horizons have a different impact on prison conditions. Prior studies, such as a 2001 study by Brian Bushee provide empirical evidence that ownership by institutional investors with a passive investment strategy and a long-term holding horizon is positively correlated with long-term firm value, whereas ownership by investors with an active investment strategy and a short-term holding horizon is positively associated with short-term firm value.

These results are primarily driven by the fact that investors with a passive investment strategy have a long-term investment horizon, and therefore these investors are more attentive to long-term outcomes. Similarly, in his most recent letter to CEOs, Fink argues that “these [short-term profit maximizing] actions that damage society will catch up with a company and destroy [long-term] shareholder value.” Therefore, institutional investors with a long-term investment horizon may have an incentive to internalize social costs.

Consistent with these arguments, I find that the negative association between ownership and mortality rates is primarily driven by long-term investors, given that neglecting to incorporate social externalities has long-term consequences both from a reputational and valuation point of view.

To establish a causal relationship between social outcomes in prisons and ownership by long-term investors with a passive investment strategy, I use a novel identification strategy that exogenously changed the ETF ownership levels in public companies that manage prisons. In particular, at the end of 2012, the Internal Revenue Service reclassified public companies that manage prisons as Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs).

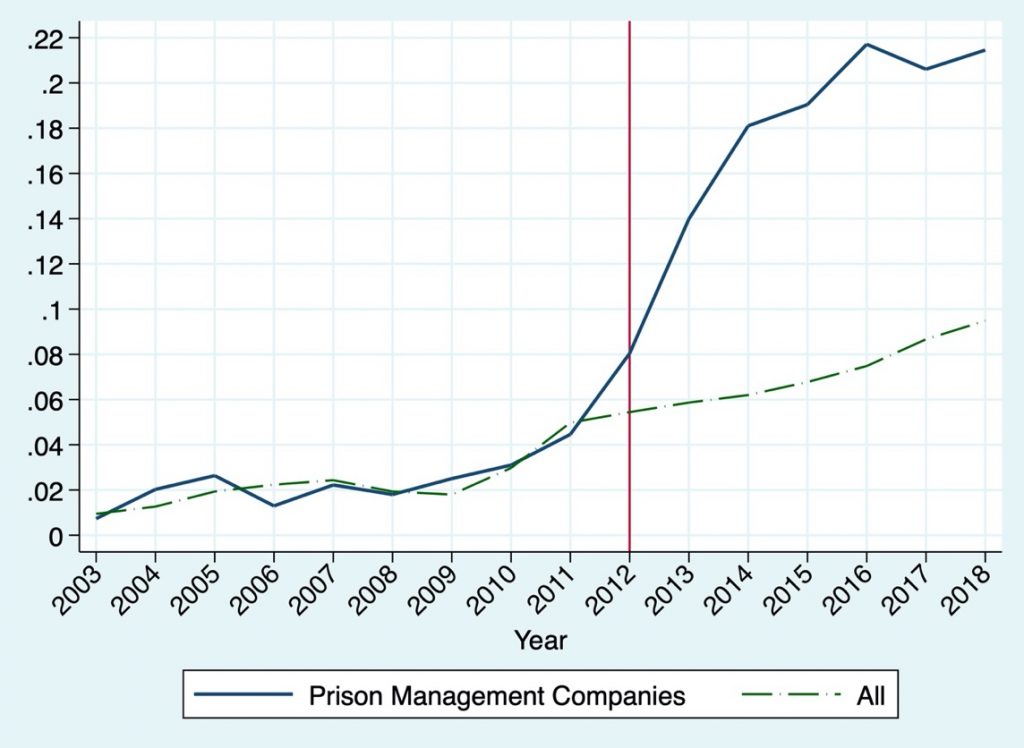

As shown in Graph 1, this tax reclassification of public companies that manage prisons led to a doubling in ETF ownership levels since these public companies entered into ETFs that track the real estate sector, whereas such patterns were not seen in other stocks.

Graph 1

In particular, using an instrumental variable approach where I rely on the exogenous change in ETF ownership in prison management companies due to the REIT reclassification, I document a causal effect of ownership by institutional investors with a passive investment strategy on social outcomes.

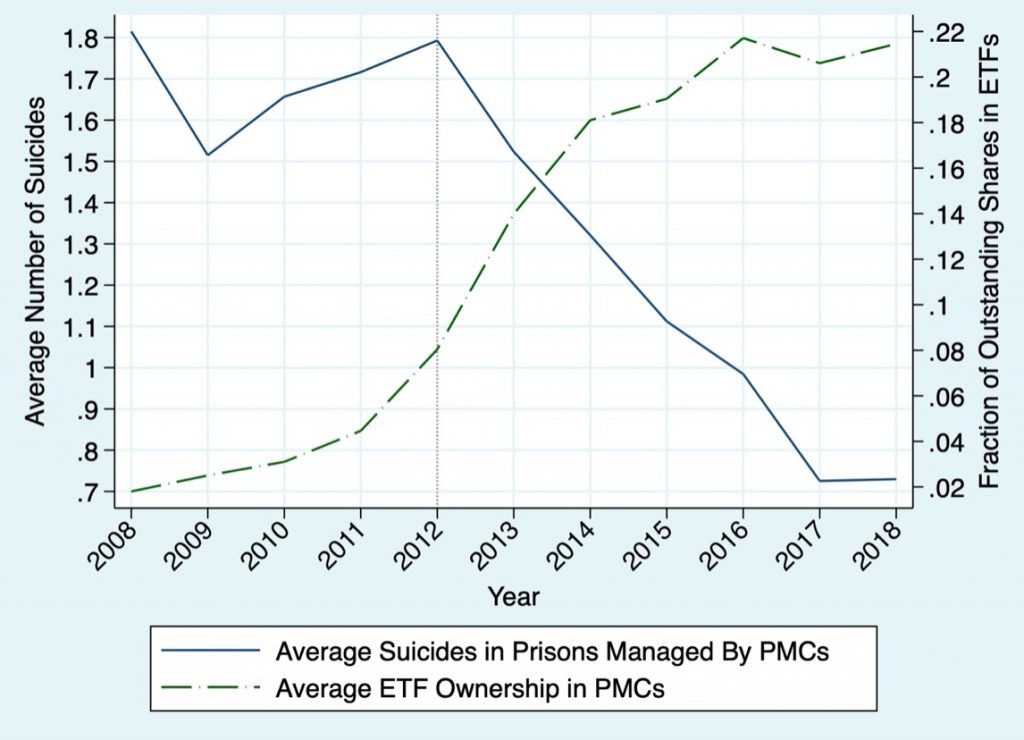

These positive effects of institutional investors with a passive investment strategy on social outcomes may also be depicted in Graph 2, which shows the relationship between ETF ownership in public companies that manage private prisons and suicide rates. I document that these improvements in prisons are likely to be driven by more educational, social, and general rehabilitation programs being offered in private prisons managed by public companies.

These results so far highlight the fact that privatization may come with a cost to society, but these social costs are partially mitigated by the monitoring role of institutional investors. To further examine why institutional investors may have an incentive to internalize the social costs of privatization, I examine whether litigation and reputation risks may play a role. In particular, using a proxy for litigation risk that measures whether the given state in which a prison is located is more friendly to plaintiffs, I find that the institutional ownership effects are stronger in prisons that are more likely to be successfully sued for negligence.

In other words, the positive effects of institutional ownership on social outcomes are more pronounced in prisons that are more likely to cause reputational or litigation damage to shareholders and the firm, given that the litigation environment is riskier.

Overall, my paper shows that privatization may come with a social trade-off when governments fail to write complete contracts. However, such social trade-offs are offset by the monitoring role of institutional investors. This is especially true for investors with a long-term investment horizon, given that these types of investors pay attention to long-term firm value and have an incentive to internalize social externalities that may harm the long-term success of the portfolio firm. My paper highlights the importance of shareholders in eliminating the tendency of firms to focus on short-term profits that may come with a cost to society.