If the Australian government wants to subsidize high-quality journalism then it should, well, subsidize high-quality journalism. The new proposed ACCC code would mess with the entire business model of tech companies and ultimately harm consumers.

Editor’s note: follow our coverage of the dispute between Google, Facebook, and the ACCC here.

We Australians are rightly proud of a number of world firsts. We pioneered the secret ballot, were the first country to allow women to stand for elected office, and we initiated the use of ranked-choice voting.

And so it is, with both a degree of parochialism but also pride, that there has been considerable public fanfare about the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s (ACCC) proposed News Media and Digital Platforms Bargaining Code which is under consideration by the Australian parliament. According to the proponents of this code, when legislated, it will be the first in the world to force technology companies to strike a fair deal in paying for content from media companies, thereby helping preserve high-quality journalism and the ensuing public benefits that flow from such journalism.

So should we chalk up another win for Australian democratic exceptionalism? I’m not so sure.

The ACCC code is often presented (for example, by ACCC head Rod Sims) as being a simple matter of tech companies paying for getting free content from the media companies that produce it. As Australia’s Treasurer Josh Frydenberg put it: “It was going to be very difficult to reach an agreement between the parties to ensure that the traditional media businesses that prepare the content, that they get rightly and fairly paid for it…This is really a question of fairness. If you prepare the content and the digital platforms are using it to bring traffic to their websites, then they should pay for it.”

The reality is considerably murkier.

Yes, tech companies play an important role in the media market through search, and social media in the case of Facebook. And yes, which articles rank highly in a news search have an impact on the profitability of media companies, and hence on their incentives to invest in high-quality journalism. But tech companies do not, in fact, make much money out of clicks on ads from news-related queries in Australia (Google reported that it made about A$10 million in such revenue in 2019).

Perhaps more importantly, the proposed bargaining code will force tech companies to give media organizations advance notice of changes to their algorithms—an extraordinary infringement on core intellectual property. And the code has substantial penalties built-in: Failure to comply with it could lead to tech companies paying fines equivalent to 10 percent of local revenue, on top of other payments to news organizations.

It is little wonder then that Google and Facebook have suggested that, if this is the price of being in the Australian market, then they might simply prefer not to be in it—severely compromising the user experience of millions of Australians who use Google, YouTube, and Facebook for news content.

It’s not hard to understand how we got to this position. An overzealous competition regulator looking to make a splash has targeted Big Tech companies. The journalists who report on the issue blame Big Tech for the loss of jobs in the media industry. And the media companies for whom they work stand to benefit handsomely from the new rules. Politicians—who live and die at the hands of the media—naturally end up siding with the press. Throw into the mix a good dose of nativism—the Big Tech companies are foreign but the journalists working for the media companies are mostly Australians—and you have a perfect storm of tech-busting sentiment that gets little scrutiny.

But is the proposed bargaining code good economics? I have my doubts. And it seems likely that issues to do with horizontal competition among media firms and appropriate investment in high-quality journalism could be better addressed with other policy tools, rather than the ACCC’s code.

The Australian Media Landscape in the Digital Era

To assess the ACCC bargaining code, one first needs to understand a few facts about the modern Australian media market.

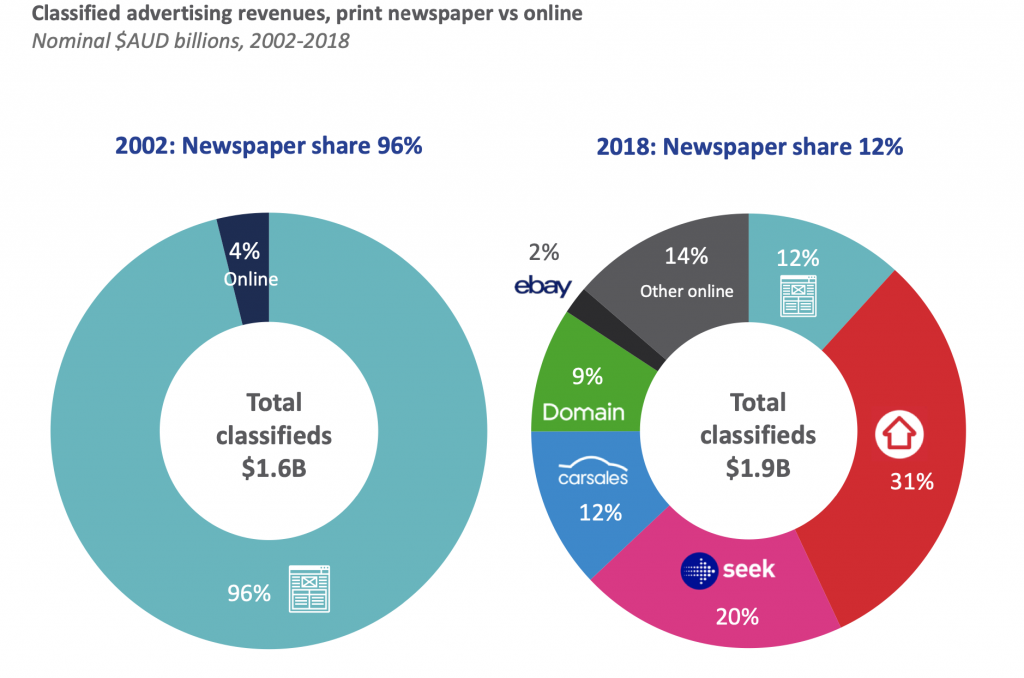

The first is that, as in most countries, Australian newspaper revenues have fallen significantly in recent decades. Consulting firm AlphaBeta found that between 2002 and 2018, newspaper revenues fell from A$4.4 billion per year to A$3.0 billion. The overwhelming majority of this decline was the loss of classified advertising, which fell from A$1.5 billion in 2002 to just A$0.2 billion in 2018. As the following chart shows, most of that was captured by online “pure-plays” targeting specific market segments such as motor vehicle sales, job ads, second-hand goods, or real estate listings. Companies like Google and Facebook captured essentially none of this revenue.

Other sources of newspaper revenues have been relatively stable. Print subscriptions have declined but online subscriptions have increased sharply. Print display advertising has fallen but has been more than offset by increases in online display revenues.

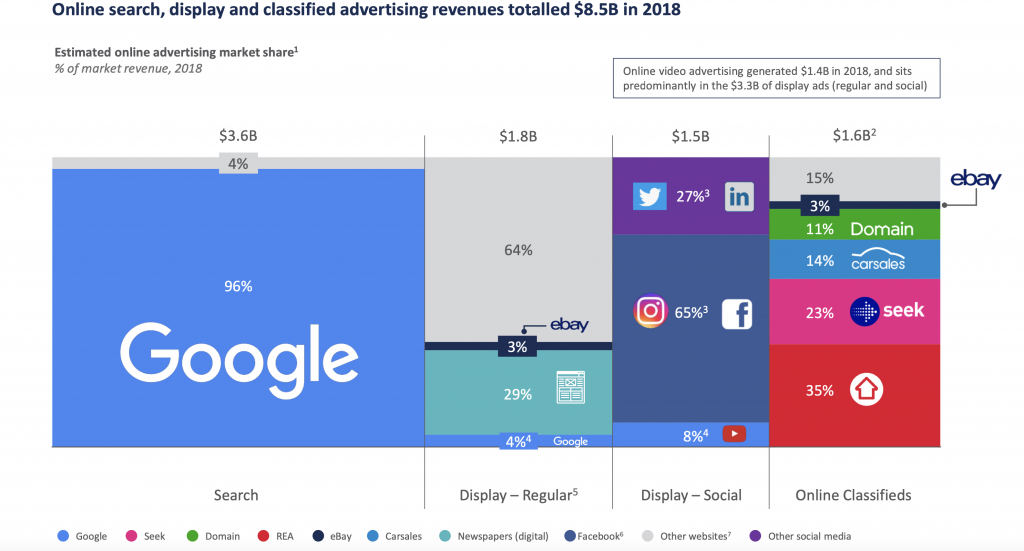

Over the same period, tech companies like Google and Facebook have captured a large share of the overall online advertising market, as the following figure highlights.

The size of online search advertising has grown from almost nothing (A$0.1 billion) in 2002 to A$3.6 billion in 2018. Most of this growth came from new sources, with only A$0.8 billion of the A$3.5 billion in revenue growth estimated to have come from print directories.

The contrasting fortunes of media and Big Tech companies are important in two ways. First, it shows that traditional media has lost about one-third of its revenues because of classified advertising being decimated. One might call this “the Craigslist phenomenon.” Second, it shows that tech companies have done very well over the same period, but not by cannibalizing media company revenues.

Yet it is arguably the decline of one sector (traditional media) and the rise of another sector (Big Tech) that makes for a tempting exercise in scapegoating. There is some relationship between Big Tech and media, and during the period that media has been hammered, Big Tech has flourished. But this is more a tale of one industry in secular decline while another is in the ascendancy, rather than tech companies outcompeting traditional media in the same industry.

“This is more a tale of one industry in secular decline while another is in the ascendancy, rather than tech companies outcompeting traditional media in the same industry.”

Competitive Pressure in the Media Market

That said, Google and Facebook are important gatekeepers of news traffic in Australia. About one-third of news content comes from Google searches and a further one-sixth via Facebook—so about half in total. But these tech companies do not allow users to bypass paywalls erected by media companies. Many major mastheads in Australia: the Sydney Morning Herald, Australian Financial Review, The Australian, The Age, and Daily Telegraph (all owned by either News Corporation or Nine Entertainment) have paywalls for accessing digital content. Indeed, these companies now generate around 50 percent of their revenues from subscriptions. And these companies employ a significant number of Australian journalists producing original content.

There are also sites like the Guardian, the national public broadcaster Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), The Conversation, New Daily, and others that offer free content. They also employ many Australian journalists producing original content. Both paywalled and non-paywalled sites also report news from other sources like the Associated Press wire service, their competitors, and broadcast media.

All these sites benefit from internet search. Search directs traffic to their sites, where the media companies can show paid advertising or even convert those customers into subscribers. Deloitte estimates that such search generates about A$218 million a year for Australian media companies through these channels. The real point of contention is one about competition among different media organizations, not between media organizations and Big Tech.

Media companies with paywalls complain that their sites rank low down the list of searches on, say, Google. This is, in general, true. Just try searching for news yourself and see which news sites are near the top. In fact, a few years ago paywalled sites weren’t even indexed by Google. These companies complain that they are disadvantaged relative to free media sites. They are.

It is unclear that Google does this intentionally—it would be natural to conclude that free sites have better click-through and therefore do better according to Google’s algorithm. In any case, it is the existence of these “free” sites apparently satiating the needs of many media consumers that causes grief for News Corp, Nine Entertainment, and other Australian media companies with paywalls.

This raises the question of whether Google or other tech companies are doing something that is not in the public interest with the way they order search results. Consider for a moment if one was a social planner designing search algorithms for news from scratch. Which results would rank near the top? It might well be socially optimal that free sites are ranked highly.

Moreover, competition in the market for news from media companies that don’t charge for content is almost surely good for consumers. It expands choice and it has, as an empirical matter, led to some high-quality entrants into the Australian media landscape such as The Guardian and The Conversation. To the extent that tech companies facilitate competition that is good for consumers, it is hard to see why they should be sanctioned for doing so, especially by the competition regulator.

The Proposed Remedy

Regardless of where one comes out on the above issues, the question remains as to whether the way in which the ACCC code reallocates bargaining power is the most efficient one. As a matter of principle, an intervention that seeks to remedy a market failure should do so in a way that preserves as much economic value as possible, consistent with correcting the market failure.

Does the ACCC code do this? Again, it appears not.

The two key elements of the code are that:

- After a stipulated bargaining period (3 months), mandatory final-offer binding arbitration will ensue; and

- Technology companies will be required to give a 28-day notice of changes to their algorithms that affect news organizations through referral traffic or the ranking of their pages.

There is also a requirement that tech companies inform media organizations about the nature of consumer data the tech companies collect through interactions with news pages.

The arbitration process involves an arbitration panel appointed by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA). The arbitration follows so-called “baseball arbitration,” where each party makes an offer and whichever offer is closer to the panel’s determination becomes binding.

As all economists know, the “gains from trade” in a bargaining situation are split among the parties to the bargain. The most useful framework for thinking about how those shares are determined is due to Nobel-prize winning mathematician John Nash (of A Beautiful Mind fame). Under (generalized) Nash bargaining, each party gets her outside options plus some share of the gains from trade (that share being reflective of the relative bargaining power). This share is known as the “Nash bargaining weight.”

The arbitration procedure above does something more than alter the Nash bargaining weight. It changes the outside options of the parties (potentially dramatically) and inserts the value judgment of a government-appointed panel. Given the relish with which politicians have sided with media organizations and against the tech companies, there is every reason to suspect that the panel members chosen will be more sympathetic to the media companies.

Given the possibility of losing a dramatic amount of completely unrelated advertising revenue in such an arbitration process, it is of little wonder that the tech companies might want to avoid being involved altogether by simply having nothing to do with media searches in Australia. This would lead to a significantly diminished consumer experience for Australians of all ages—from kids doing school projects to citizens unwilling or unable to pay for subscription services wanting to stay informed. In short, it is a highly value-destroying regulation.

The algorithm-sharing provision is potentially even worse. We will have to wait until seeing the final details of the legislation to understand exactly how it would work, but it is hard to see how one can give effect to the intent of it without requiring tech companies to share important details of their algorithm. Those details are, in short, the very heart of their business. One could expect tech companies to avoid having to do so at essentially all costs. Let’s not forget that Google became Google when its founders had a really good idea and built a better “search mousetrap.” Giving other companies visibility into that mousetrap constitutes an extinction-level risk for the tech companies.

As a side note, opaqueness around search and other algorithms is important to prevent “gaming” of those algorithms—a core component of what it means for them to work well. This “optimality of opacity” is an important phenomenon in a range of contexts (especially in incentive schemes), as I pointed out in a 2018 paper with Florian Ederer and Margaret Meyer.

Other Regulatory Tools

One thing there is fairly general agreement about is that high-quality news and journalism is a critical component of a well-functioning democracy. Whatever the market forces are—such as the demise of classified advertising—that have put the funding of such journalism under threat, there is a strong case for government intervention.

The most natural intervention is to subsidize high-quality journalism. This is something that has been done for decades through national broadcasters such as the BBC in the UK and, indeed, the ABC in Australia. This occurs in a more decentralized fashion in the US through organizations such as PBS, which rely on private fundraising.

To put this all in perspective, the figures outlined above show that the entire media industry in Australia has lost roughly A$1.4 billion per year in revenue. This is, according to the media companies themselves, the sum total of what has put journalism at risk. Let’s be generous and adjust for wage inflation and call that A$2 billion a year.

We could discuss clever mechanisms to raise this money and then how to allocate it to the right media firms—perhaps acknowledging that there is something odd about taxpayers writing checks to Rupert Murdoch. But let’s bracket all that.

If the Australian government wants to subsidize high-quality journalism then it should, well, subsidize high-quality journalism. Given that the 10-year bond rate in Australia is currently about 90 basis points, the carrying cost of A$2 billion a year of media subsidies would be A$18 million a year. That’s 72 cents per Australian per year. Seventy. Two. Cents.

I think we can cover that.

Messing with the entire business model of tech companies that deliver huge value to Australian consumers would be a vastly inferior option.