The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s draft news media bargaining code for digital platforms has elicited aggressive responses from both Google and Facebook and much online commentary. To properly comprehend the dispute, however, one needs to understand where it came from and what it actually says.

The question of how digital markets should be governed is constantly in the news. However, even by today’s heightened standards, the discussions around the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s draft news media bargaining code for digital platforms has been extraordinary. Before the ACCC released the code, it had already been covered by the New York Times; on the day of its release, it has made the headlines of The Wall Street Journal, the BBC, and many other outlets.

The code has also drawn quick reactions from Google, which published an open letter stating that it would “put the free services they use at risk,” and from Facebook, which threatened to “reluctantly stop allowing publishers and people in Australia from sharing local and international news on Facebook and Instagram.” Some condemned the Australian code as a “shakedown,” while others praised it as opening a path towards a “decentralized regulation” of digital platforms.

All this attention is well-deserved. The draft bargaining code is a significant innovation to the governance of digital markets and, as such, should receive scrutiny from academics, policymakers and society more broadly. But first, it’s important to understand where the draft code comes from and what it actually says.

The Origins of the Draft News Media Bargaining Code

The new draft media bargaining code stems from the ACCC’s Digital Platforms Inquiry, published in July 2019. Commissioned in December 2017 by then-Treasurer and current Australian Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, the ACCC was to assess “the extent to which platform service providers are exercising market power in commercial dealings with creators of journalistic content and advertisers” and their impact “on the level of choice and quality of news and journalistic content to consumers,” among others.

The Australian government was not alone. The ACCC’s final report joined a range of expert reports on the status of competition in digital markets in general. It also joined the UK’s Cairncross Review and the Media Subcommittee chapter of the Stigler Report in addressing the impact of digital platforms on the news media business.

In a rough summary, the ACCC concluded that Google had substantial market power in the Australian markets for general search (with a 95 percent market share) and search advertising (96 percent), and that Facebook had substantial market power in the Australian markets for social media services (80 percent) and display advertising (51 percent). Three of the report’s eight chapters—around 200 pages— explore the impacts of this dominance on the Australian news media market.

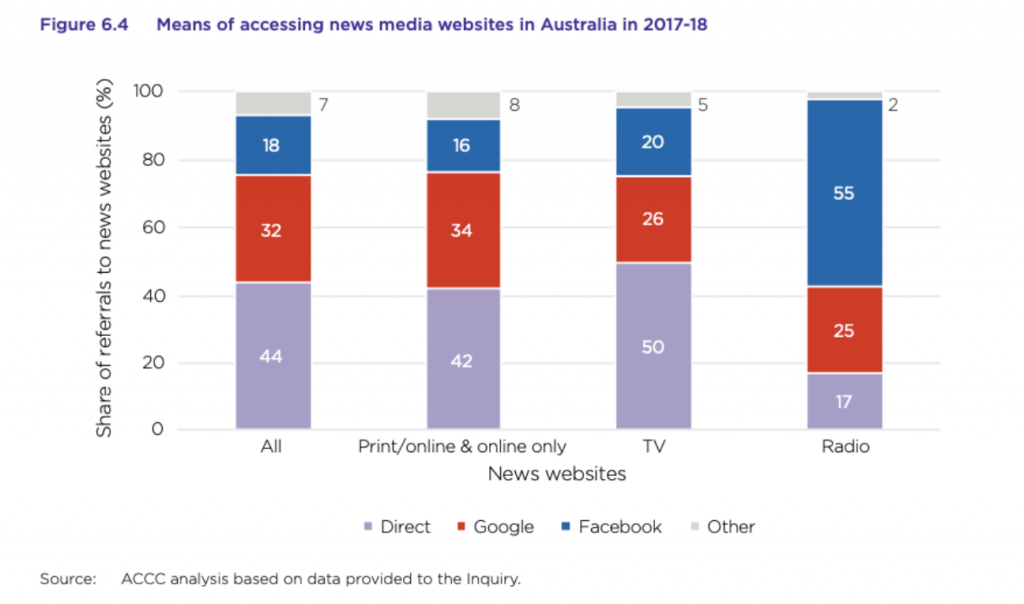

The ACCC argues that Google and Facebook are key gateways to online news media, putting news media companies in a position of economic dependency on both platforms (with Apple News growing quickly as a third alternative). This creates fundamental imbalances in bargaining power that would result in news companies accepting less favorable terms of trade. The ACCC also expressed concerns that significant growth in Apple News would lead to problems, but that it was not an “essential business partner” to news media companies in the way that Google and Facebook are.

In particular, the ACCC finds that Google’s search services were essential to news distribution. Its analysis found that Google displays the “Top Stories” carousel for searches with a news intent on 8-14 percent of all Australian searches. The ACCC recognizes that for the most part, Google does not display ads against search results for news queries. However, it finds that Google’s ability to attract consumers to its platform relies on the provision of a high-quality search service that includes accurate news hyperlinks. These consumers then also use Google for non-news searches that Google could monetize, so that searching for news is an integral part of Google’s services.

Similarly, the ACCC stated that 46 percent of Australians use social media as one of (or main) ways of accessing news, with Facebook and YouTube being the main players. Facebook estimated that around 4 percent of the content on users’ newsfeeds would be actual news, with the company also relying on hyperlinks and snippets of news content. While changes Facebook made to its core algorithm to keep consumers within Facebook diminished referrals to news media companies, the ACCC believes that Facebook is still an essential gateway and platform for news companies to build their brands, in particular companies interested in accessing younger demographics and local news media.

The ACCC affirms that Google and Facebook leverage their privileged bargaining position against media companies through different means (the analysis, however, focuses most on Google). The first was Google’s former First Click Free Policy, which from 2008 to 2017 mostly required that companies provide five articles per day for free to Google users or be demoted in search results.

The second is Google’s impositions on the length and content of snippets. The ACCC found some conflicting evidence on whether the size of snippets actually mattered for directed traffic, and also acknowledged that news media companies can unilaterally opt out of providing snippets to Google. However, it claimed that a refusal to provide snippets could lead to a demotion in search results and substantially less referral traffic from Google. Therefore, companies would be compelled to have their content scraped by Google and would not be able to experiment/negotiate the size of the snippet.

The third is Google’s prioritization of the AMP format. On mobile searches, Google only displays top stories from companies that upload the stories to Google’s cache servers. This ensures a faster loading time, but restricts news media companies’ ability to monetize through ads and subscriptions.

AMP is an industry standard, but the ACCC found that Google highly influenced its design. By requiring providers to host content on Google’s servers and determining the display standard, Google negatively impacts attribution (advertisers see the traffic going to Google and to the media pages, boosting Google); monetization (AMP restricts certain types of ads); access to user data (because the user stays in Google’s ecosystem, companies collect less personal data they use for ads); and retention and brand awareness (AMP encourages users to browse providers while media companies want to retain users in their environment).

The ACCC expressed similar concerns with regards to Facebook’s significantly less used Instant Articles for mobile users. It is also worth mentioning that Bing and DuckDuckGo also rely on a similar functionality.

Finally, the ACCC pointed to problems related to the transparency of Google and Facebook’s algorithms (both companies change their codes with limited notice to media businesses, despite their heavy impact), restrictions on the data shared with publishers, and recognition of original content as examples of problems arising from the unbalanced bargaining power between the parties. The ACCC, however, acknowledged that many of these policies benefit consumers by diminishing subscriptions and search costs.

The Commission proposed the creation of a code of conduct through which Google and Facebook would commit to remedy this bargaining imbalance. There were different suggestions: a complainant asked for an access regime that would give publishers almost absolute control over their content; an industry association proposed the creation of both a licensing arrangement and a collecting society, as done in copyright. The ACCC, however, opted for a code of conduct to encourage negotiation between the parties and to enable the Commission to intervene and “equalize the bargaining power” if necessary. It also suggested that Google and Facebook should be given nine months to develop a voluntary code of their own—otherwise, the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) and the ACCC would intervene and mandate changes.

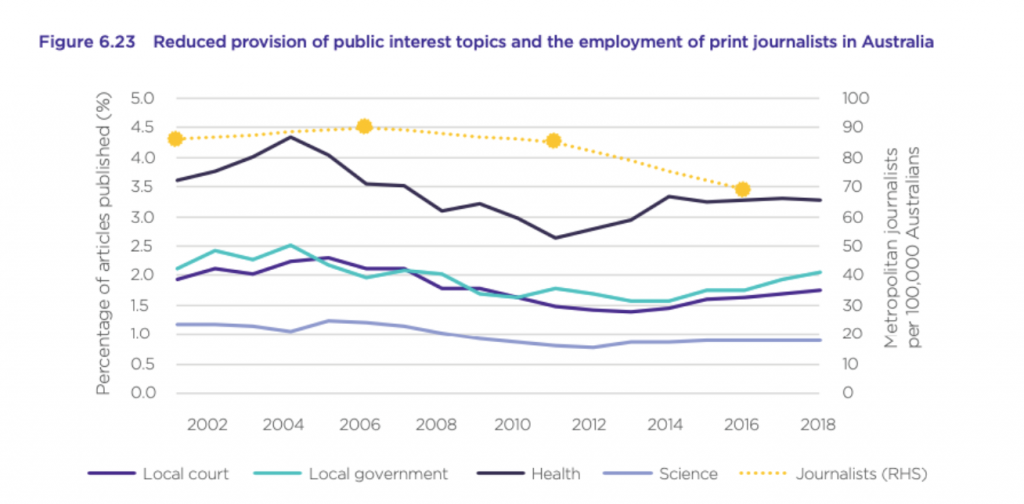

Importantly, the same report also addressed concerns about the quality and diversity of news journalism more broadly. It finds a significant decline in the number of journalists in Australia, with particular impact on public interest journalism, including a 26-42 percent decline in the number of articles reporting on local government, local courts, health, and science.

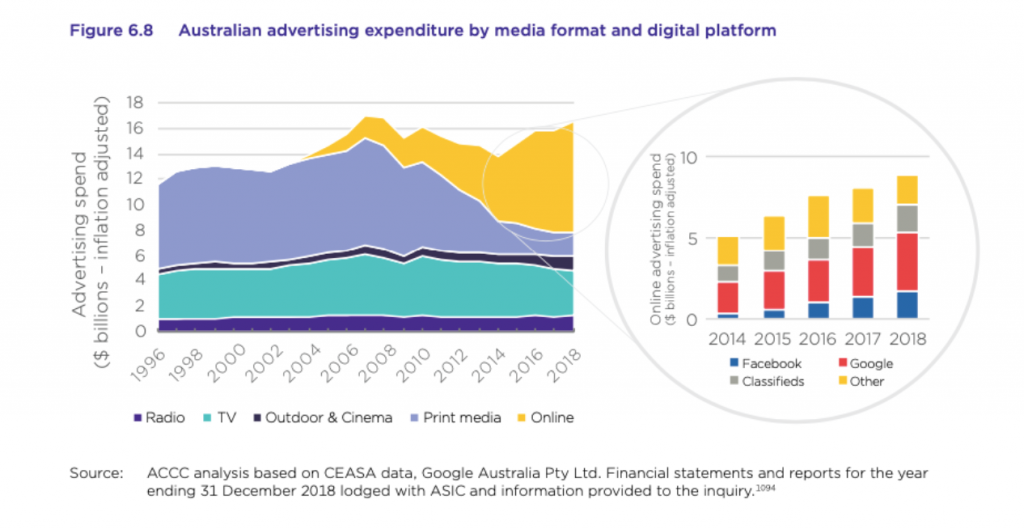

It also found that as audiences moved online, Australian print publishers lost almost 54 percent of their revenue (classified ads), largely due to the emergence of specialized online marketplaces. However, this loss of revenue continued even after classified ads moved online, as Google and Facebook increased their online advertising revenue (in part at the expense of publishers).

In order to help print publishers address the decline in ad revenues, the ACCC recommended increased funding for public journalism, better targeting of existing public funds and grants to support journalism, and changing tax deductibility to encourage philanthropic donations to newsrooms. These would be complementary to Google and Facebook’s bargaining code.

From a Voluntary to an Imposed Code

This, however, was July 2019. By December of that year, the ACCC started intermediating conversations between Facebook, Google, and news platforms, and by April 2020 it reported to the government that payments for content would probably not be settled by voluntary negotiations. In April, the Australian Government instructed the ACCC to develop a mandatory code, ordering that the first draft be published by July 2020. The ACCC first published a “concepts paper” in May 2020, which received 40 contributions, including from Google and Facebook.

Google argued that it was not the cause of journalism’s decline, but rather provided significantly more resources to publishers than the other way around. Google calculated that only 1 percent of queries in Australia were news-searching queries (against the 8-14 percent figure the ACCC found) and that it earned only 10 million AUD ($7.3 million) in ads for those queries. In exchange, Google referred billions of free clicks to publishers’ websites. Google also held that displaying snippets does not infringe copyright, antitrust, or any other laws, and that news publishers could opt out. The company claimed it already provided news publishers with plenty of data and was against any form of algorithmic transparency.

In conclusion, Google said that a “Code should not require search engines to pay for crawling, indexing and displaying links and extracts of websites, or require publishers to pay us for these services,” because this would create wrong incentives for companies to create large volumes of low quality content, may favor large news organizations over smaller publishers and other local companies and could undermine trust in Google’s services. Google said it could support some collective bargaining, but not collective or mandatory licensing.

Facebook argued that the fact that its algorithmic change in 2018 diminished the quantity of news in the News Feed but increased engagement within Facebook was proof that it did not need news to operate. This notwithstanding, Facebook saw itself as a supporter of Australian journalism, generating approximately 2.3 billion link referrals to Australian news publishers between January-May 2020 (which it valued at 195 million AUD, or $140 million, based on the average cost-per-click for the platform), participating in revenue sharing programs such as Instant Articles (2 million AUD), executing some commercial deals for content, and providing data to publishers (among other initiatives).

Facebook was not opposed to a code that provided some clarity regarding algorithmic changes and available user data. However, it was against any change that would not “uphold the primacy of commercial negotiations between platforms and publishers.”

On July 31st, the ACCC finally published its draft news media bargaining code, which would require approval by the Australian Parliament. The Bill establishes that:

- The Australian Treasurer designates the platforms for which the code is applicable/mandatory, based on the Treasurer’s determination of “a significant bargain imbalance between Australian news providers” and the platform. This definition would initially apply to Google and Facebook, but could include Apple in the near future.

- News entities/corporate groups can apply to the ACMA to be registered as a news business. In order to qualify, the entity must: (i) operate or control a news business; (ii) have an annual revenue above 150,000 AUD in the past year or in 3 out of the 5 past years; (iii) create and publish online content that is predominantly core news; (iv) operate predominantly in Australia and serve Australian audiences; (v) be subject to the Australian Press Council or have internal rules regarding the provision of quality journalism; and (vi) have editorial independence. News media companies can bargain individually, as part of a commercial group, or even collectively.

- For these companies, digital platforms must (i) list and explain all the data they have on news media users, what they share, and how the news media can access the rest of the data; (ii) provide a 28-day notice to news media businesses of core algorithmic changes that are likely to significantly affect registered news businesses (they can provide an ex post notice if the change related to a matter of urgent public interest); and (iii) provide similar notices in cases of changes to how the news is displayed within the platform or to the display of advertisements.

- News media entities should be able to remove or filter comments made by users on their products.

- Digital platforms must present a proposal within six months on how they plan to better recognize original news content and update this proposal every year.

- Digital platforms must not discriminate between registered businesses or between registered and unregistered news businesses. Importantly, the ACCC clarified (though this is not on the draft) that a decision by digital platforms to privilege international news over Australian news or to cease carrying Australian news altogether would be considered discrimination and subject the violating platform to enforcement action;

- Registered news companies can notify digital platforms of their interest to negotiate for access to their content. If a news media entity does so, platforms must: (i) open a bargaining process with the news media company; (ii) negotiate in good faith; and (iii) provide data that is relevant to the negotiation (and vice-versa).

- If the parties cannot reach an agreement on the value of the content after at least three months of negotiation, they can request an arbitration. The ACMA will maintain a list of arbiters for these disputes. Each of the parties has to present a binding final offer to the arbitration panel and the panel has to either accept one of the final offers or, if it sees that both offers are highly harmful to Australian consumers or news services in Australia, define a value.

- If the parties do not comply with the code, they can be fined up to 10 percent of their annual turnover in Australia over the 12 months preceding the violation.

What Comes Next?

The rest is a bit of history. Google quickly published an “Open Letter to Australians” to “let you know about new Government regulation that will hurt how Australians use Google Search and YouTube” because the code “would force us to provide you with a dramatically worse Google Search and YouTube, could lead to your data being handed over to big news businesses, and would put the free services you use at risk in Australia.”

Some days later, the ACCC published a response, where it said that everything Google stated was not true and that it was simply trying to address a significant power imbalance between Australian news media and Google and Facebook, protecting the well-functioning of the Australian democracy.

On August 31st, Facebook published an “Update about changes to Facebook’s services in Australia,” saying that the code “ignored important facts about the relationship between the news media and social media” and that if the code were to become law Facebook would stop allowing Australian users to share local and international news on Facebook and Instagram. In response, Australian authorities said that they “do not respond to coercion or heavy handed threats.”

In the meantime, the consultation period of the draft code closed in late August and the ACCC is now evaluating comments to propose a final bill to the Australian parliament. This means that we have only seen the beginning of this fight, which is but one of the many disputes going on around the world. Facebook and Google are not making empty threats—indeed, Google pulled Google News out of Spain after the country changed Copyright laws, and waged (and largely won) a similar battle against the EU’s Copyright Directive.

Yet, Australian politicians and regulators likely see themselves as simply extending to the internet a concept of must-carry obligations that apply to telecom companies in multiple jurisdictions (though, I believe, not in Australia), something that is usually within the traditional realm of any democratic process. As such, we cannot rule out the possibility of a hard standoff between the Australian government and both companies.

No matter what happens, this process joins President Trump’s executive orders on TikTok and WeChat as yet another blow to the utopian borderless global internet. We already know the next strike: the EU is bound to publish its highly anticipated proposal for a Digital Services Act to address the role of “large online platforms acting as gatekeepers” in the next couple of months. Expect many more headlines and threats when that happens.