A new study looks into how Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign affected police behavior toward Black Americans and finds that the probability that a Black driver would be stopped by police increases after a Trump rally, suggesting that Trump’s rallies led to nearly 30,000 additional stops of Black people by the police in the month following his events.

Editor’s note: catch up on our latest coverage of policing and police reforms.

The United States has seen a resurgence of racial and ethnic turmoil and tensions during Donald Trump’s presidency. The neo-Nazi “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville in 2017, the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting in 2018, and the El Paso shooting in 2019 are some of the most visible examples of this worrying phenomenon. The country is currently engulfed in the largest racial turmoil since the Civil Rights movement, ignited by the murder of George Floyd by white Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin.

Some directly point to Trump’s inflammatory leadership as the reason for this turmoil, as former Secretary of Defense and retired general James Mattis recently did in The Atlantic, when he wrote that “Donald Trump is the first president in my lifetime who does not try to unite the American people—does not even pretend to try. Instead, he tries to divide us.”

Whether Trump’s rise to prominence in 2016 was merely the symptom of racial resentment already there, or whether Trump itself is the cause of its radicalization, is still an open question.

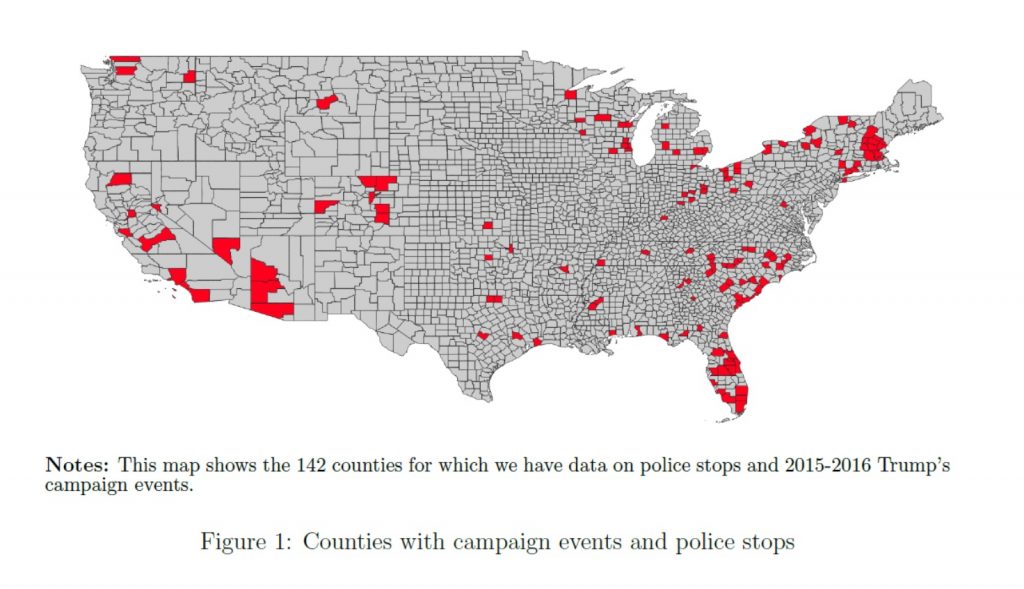

In new research, we study how Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign has affected the expression of racial prejudice and discrimination against Black Americans in one of its most fundamental and violent dimensions: police behavior. To do so, we use data on nearly 12 million vehicle stops by the police in 142 counties where Trump had held a campaign rally in 2015 or 2016, as shown in Figure 1.

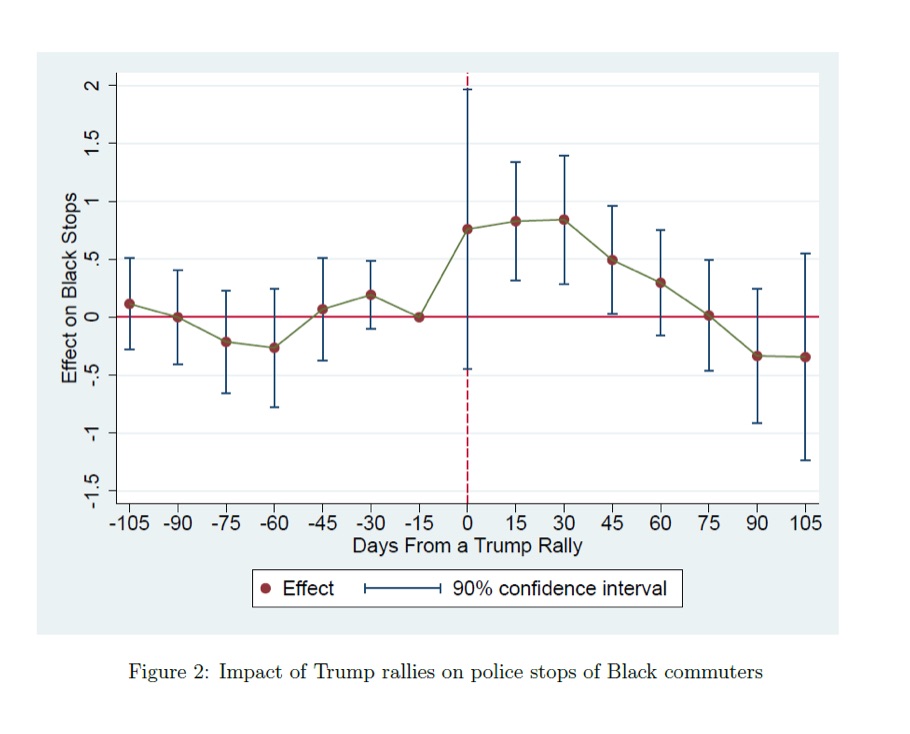

We find that the probability that a driver stopped by the police is Black increases after a Trump rally. As shown in Figure 2, the effect is immediate, constant in magnitude for the first 30 days after a rally, and lasts for at least 50 days. Our estimates suggest that Trump’s rallies led to nearly 30,000 additional stops of Black people by the police in the month following the events.

Moreover, we observe no effect for offenses that would automatically trigger a police stop or police intervention like accidents, collisions, criminal offenses including assault, fleeing the scene of a crime, fleeing the police, speeding, driving an unregistered car or a car with a defective license plate, or brake violations. Instead, the effect is entirely explained by discretionary stops by police, where the offense is either only revealed after a stop (e.g., driving without a license) or subject to value judgment and discretion by the officer (e.g., following another vehicle too closely or generally “careless” driving).

We do not detect any change in the driving or criminal behaviors of drivers. We also do not observe any increase in the rate of stops of other minorities, nor any effect of rallies held by Hilary Clinton, the Democratic contender for the Presidency in 2016, nor by the other main contender for the Republican nomination in 2016, Ted Cruz. Taken together, our results suggest that the change in police behavior after a Trump rally is unjustified and racially-motivated, specifically against Blacks.

Although the effect of large presidential rallies is larger, we nonetheless find a significant effect of smaller rallies, earlier in the race, when Trump was still only a marginal candidate for the Republican nomination. Four years into his presidency, one can only speculate about the total and cumulative effect of his presidency on police behavior towards African Americans.(( Although fatal encounters between police officers and Black civilians have tended to capture more of the media’s attention, over-enforcement of minor infractions and the kind of unjustified stops by the police that we document in this paper provide a daily and generalized expression of discrimination against minorities. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 8.6 percent of US residents aged 16 and over, more than 20 million people, were pulled over by the police during a traffic stop in 2015. Our own estimates suggest that, at baseline, Black drivers were overrepresented by a factor of two compared to their proportion in the population.))

At first, these results may seem odd given that Trump’s inflammatory remarks during his campaign were often directed towards Hispanics and Muslims, while we only observe an increase in police stops of Black drivers. We interpret this result as the manifestation of a dog-whistle effect, whereby coded language appeals to deep-seated stereotypes of groups that are perceived as threatening. In other words, individuals prejudiced against Blacks see in Trump’s speeches a confirmation of their racist views.

We provide two pieces of empirical evidence that supports our interpretation. First, we show that the effect of Trump’s rallies is much larger in areas with more racist attitudes today, or that relied more on slavery historically. By contrast, we do not find any heterogeneity of the effect along other dimensions, including income, education, political affiliation, or severity of the recent trade shock with China.

Secondly, we use data from a 2016 online experiment and we show that respondents who were already prejudiced against Blacks became more prejudiced when exposed to Trump’s inflammatory speech on violent Hispanic immigrants. Strikingly, the effect is specific to prejudice against Blacks (as opposed to other racial minorities, such as Asians or Hispanics, for whom no effect is observed) and specifically that Blacks are violent (as opposed to other dimensions of prejudice against Blacks, for example that they might be lazy, or lack intelligence).

Overall, this research shows how the rhetoric used by highly visible individuals can have tangible consequences. Even when Donald Trump was not holding any governmental position and many polls placed his presidential victory as unlikely, we show that his rallies had an effect on police behavior towards Black drivers. This is particularly striking given that the explicit xenophobic views of Trump were almost completely targeted towards Hispanics and Muslims. This result contributes to the ongoing debate regarding the value and cost of freedom of speech.

These findings are also of significant policy relevance because of the many indirect effects that racially targeted behavior by police may have on minorities. For example, unjustified police repression can act as a way of voter suppression, when disabused citizens extend their lack of trust in the police to all public institutions. As recent research shows (Williams 2019), historical discrimination and violence against Blacks are associated, to this day, with lower voter registration by Black voters.