This week’s Congressional hearing produced evidence of anticompetitive conduct that state attorneys general and private enforcers can use to pursue the dominant platforms under existing antitrust laws. It also uncovered behavior that does not fit within antitrust’s ambit but can be used to support new laws that would either expand the scope of antitrust or attack the conduct outside of antitrust.

There are so many great write-ups of the Big Tech hearing, from David Dayen to Franklin Foer, that it’s hard to add much by now. For a fleeting moment, Congress channeled its inner Justice Brandeis— David Cicilline (D-RI), Chairman of the House Antitrust Subcommittee, quoted Brandeis in his opening and closing remarks—and challenged the monopoly power of the tech titans. It felt like the ground was shifting.

As explained so eloquently by Foer, the hearing exposed the threat that unchecked monopoly power poses to capitalism and democracy. This concern was expressed on both sides of the aisle, which significantly raises the likelihood that the next Congress will pass new laws to regulate the tech giants.

With the exception of one curious review in The Economist, most reviews of the hearing—from the Washington Post (Dana Milbank, Geoff Fowler, Tony Romm) to CNN (Brian Fung) to the New York Times (Cecilia Kang and David McCabe)—convey a sense that the Tech CEOs were outmatched and lost ground.

The hearing proved useful in two dimensions. For anticompetitive conduct uncovered by the hearings that fits within the ambit of antitrust, Congress produced evidence that can be used by state attorneys general and private enforcers to pursue the dominant platforms under existing antitrust laws. It also serves to embarrass the federal antitrust agencies that sat by fecklessly, ignoring incriminating evidence, while the platforms gobbled up any potential rival.

As for anticompetitive conduct that does not fit within antitrust’s ambit, the evidence can be used to support new laws, which could either expand the scope of antitrust or attack the conduct outside of antitrust.

For example, the issue of “cloning,” or copying the functionality of an app or product, came up repeatedly during the hearing. Members of all stripes grasped how cloning by a dominant platform was different from a grocery store’s private-label brand, in the sense that a giant company like Amazon could access information about a vertical rival that no grocery store could hope to achieve.

Members also recognized that cloning could discourage edge innovation. But cloning doesn’t fit neatly into an antitrust rubric, and intellectual property protection governs rules over copying. To prevent cloning, the key is to ban two proxies for it—the misappropriation of data (which gives platforms the ability to clone) and self-preferencing (gives platforms the incentive to clone).

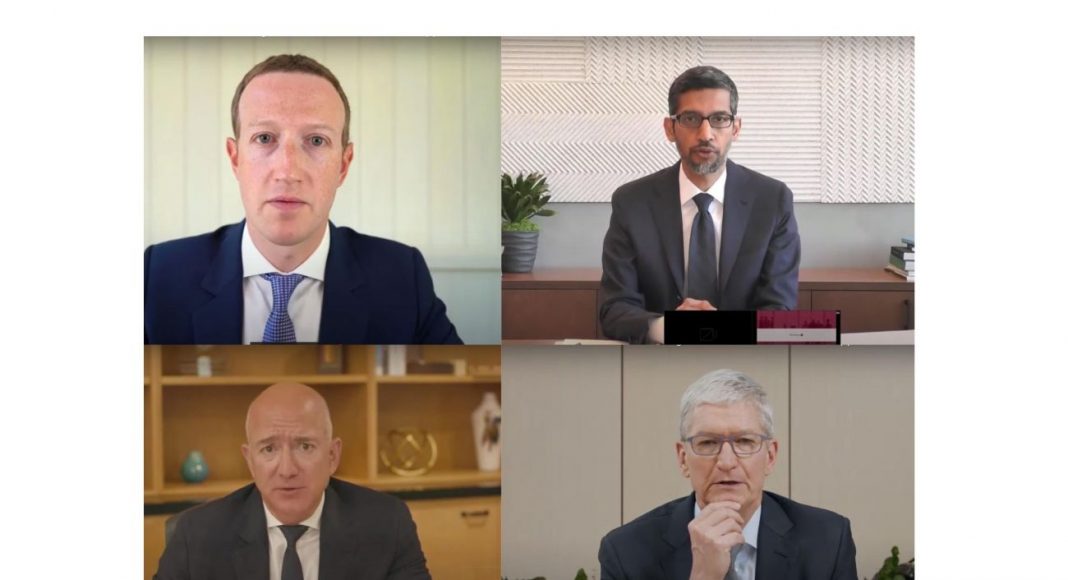

Whether due to poor preparation, general cockiness, or plain ignorance of the antitrust laws, the four tech CEOs who testified during the hearing—Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, Google’s Sundar Pichai, and Apple’s Tim Cook—didn’t seem to grasp the severity of their infractions.

Further, the evidence uncovered exposed a thuggish mentality among the platforms: Defy the platforms at your own risk! If a website didn’t submit to Google’s lifting its content, it was disappeared from search results. If a merchant didn’t buy fulfillment from Amazon, it was disappeared from the Buy Box. The only way to stop a flood of counterfeits was to pay Amazon more money for ads. One merchant even went so far as to tell Congress that it likened Amazon to a “drug dealer.”

In the spirit of this week’s return of professional baseball and basketball to ESPN’s Top 10 Plays, here’s a list of the Top 10 admissions that were surrendered by the four tech CEOs during the hearing:

10. During early questioning by Rep. Cicilline, we learned that Google lifted content from other websites, including Yelp, for its affiliated local search properties. Company emails revealed “Employees ‘started to fear competition from certain websites [and] web pages that could divert search traffic and revenue from Google.’” Google then steered users to the cloned content. If the content provider complained about its treatment, it could be disappeared from search. Pichai didn’t deny the allegation, noting that “just like other businesses we try to understand trends from, you know, data, which we can see, and we use it to improve our products for users.”

9. Through questioning by Rep. Scanlon (D-PA), we learned that Amazon was prepared to lose $200 million in a predatory strategy to sink Diapers.com, then its main competitor in the baby care area. No upstart could afford to play on those terms. Amazon acquired Diapers.com in 2011 and shut it down in 2017.

8. Through questioning by Rep. Johnson (D-GA), we learned that mobile-phone accessory company Pop Socket was told to buy $2 million in ads from Amazon in order to secure Amazon’s assistance with preventing the sale of counterfeits of Pop Socket’s accessories. When asked whether permitting counterfeits was profitable, Bezos insisted that Amazon only makes profits on counterfeits “in the short term.”

7. We learned through questioning by Rep. Scanlon that Amazon forces sellers to take its fulfillment service as a condition of getting access to the coveted Buy Box. This seems like a straightforward tying arrangement that fits squarely within antitrust’s orbit.

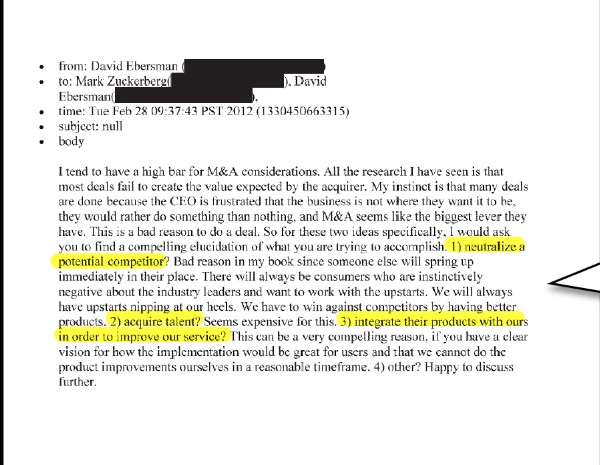

6. Rep. Nadler (D-NY) uncovered testimony that Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram was motivated in part to “neutralize a potential competitor.”

Zuckerberg testified that “I’ve been clear that Instagram was a competitor in the space of mobile photo sharing.”

5. When asked by Rep. Jayapal (D-WA) about whether Facebook copies app functionality of potential acquisition targets and vertical rivals, Zuckerberg admitted that Facebook has “adapted certain features.” Facebook uses the threat of copying as leverage to secure buyouts; one seller was concerned that Facebook would go into “destroy mode” if the offer was declined.

4. We learned through Rep. Johnson that, when it became public that Facebook was using Israeli company Onavo to monitor other apps, Onavo got kicked out of Apple’s App Store. When Facebook turned to other surveillance tools like Facebook Research App, it too was thrown out of the App Store. Rep. Johnson asked whether Facebook used that capability to identify acquisition targets, presumably because he knew the answer.

3. Most Republicans Members lost sight of the competitive aspect of the hearing, focusing instead on why social media companies take down misinformation relating to Covid-19. In skillful questioning by Rep. Gaetz (R-FL), however, we learned Facebook internally referred to its acquisition strategy as a “land grab,” consistent with anticompetitive intent.

2. Even though he came out somewhat better than his peers during the hearing, Apple CEO Tim Cook got entangled by deft questioning by Rep. McBath (D-GA). Parents came to depend on independent parental control apps like Kidslox. When asked why Apple removed those competitors from the App Store when it introduced Screen Time (an affiliated clone), Cook insisted that Apple was “concerned, congresswoman, about the privacy and security of kids.” But Rep. McBath countered that Apple allowed the independents back into the store with no changes to privacy, suggesting Apple’s privacy justification was a pretext for the real motivation (to remove a rival).

1. When asked by Rep. Demings (D-FL) why Facebook restricted API access to Pinterest but not to Netflix, Zuckerberg admitted that Pinterest was a social competitor to Facebook. Unbeknownst to Facebook’s CEO, such discriminatory refusals to deal are potentially illegal under the antitrust laws.

Disclosure: Hal Singer does not currently work for or against Amazon, Google, Facebook, or Apple in any pending antitrust litigation or consultation. He has previously consulted Apple in a copyright dispute in Canada. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Econ One or its members.