Government proponents of prison labor should be mindful of the potential for negative effects, including increased incarceration rates and citizens’ deteriorating views on state legitimacy. Using prisons as a source of labor to serve economic interests can create perverse incentives for incarceration and significantly reduce long-term trust in legal institutions like police.

With around 11 million people incarcerated globally and the number rising daily, many governments around the world have advocated using prisoners for work on everything from fighting fires to making hand sanitizer to combat pandemics. In the US alone—which has the highest incarceration rate in the world, with around 700 prisoners per 100,000 people or 0.7 percent of the total US population incarcerated—prison labor contributes to a lower bound estimate of $2 billion a year in industrial output.

From the US to China and Tanzania, governments are realizing that prisoners can be a source of cheap labor to boost their economies. But when prisoners are viewed in these terms, what are the consequences, if any, on incarceration rates? And how might the adoption or expansion of prison labor to serve extrajudicial interests affect citizens’ perspectives on the legitimacy of their judicial systems and trust in legal institutions, such as police?

Answering these questions is crucial, particularly in light of recent events and protests in the US and around the world centered around injustices in policing and in the criminal justice system. In new research, we answer these questions using evidence from 65 years of archival data on prisons in colonial and postcolonial Nigeria from 1920 to 1995.

British colonial rule in Nigeria extended formally from 1914 to 1960, with British government presence going back to the 1860s. Nigeria’s colonial experience, especially with regards to the prison system, presents a useful context to study the previously mentioned questions on the effects of prison labor. Colonial Nigeria was—and Nigeria today still is—the largest country in Africa based on population size and had relatively high incarceration rates that varied within the country. For context, in 1940 Nigeria had an incarceration rate of about 0.4 percent of the total population, a figure larger than the US average incarceration rate of less than 0.2 percent over the same period.

To put these numbers in perspective, colonial Nigeria was incarcerating a significantly larger proportion of its population than countries in Europe (0.06 percent of the total population) at the time and around the same proportion of its Black population as the US was imprisoning.

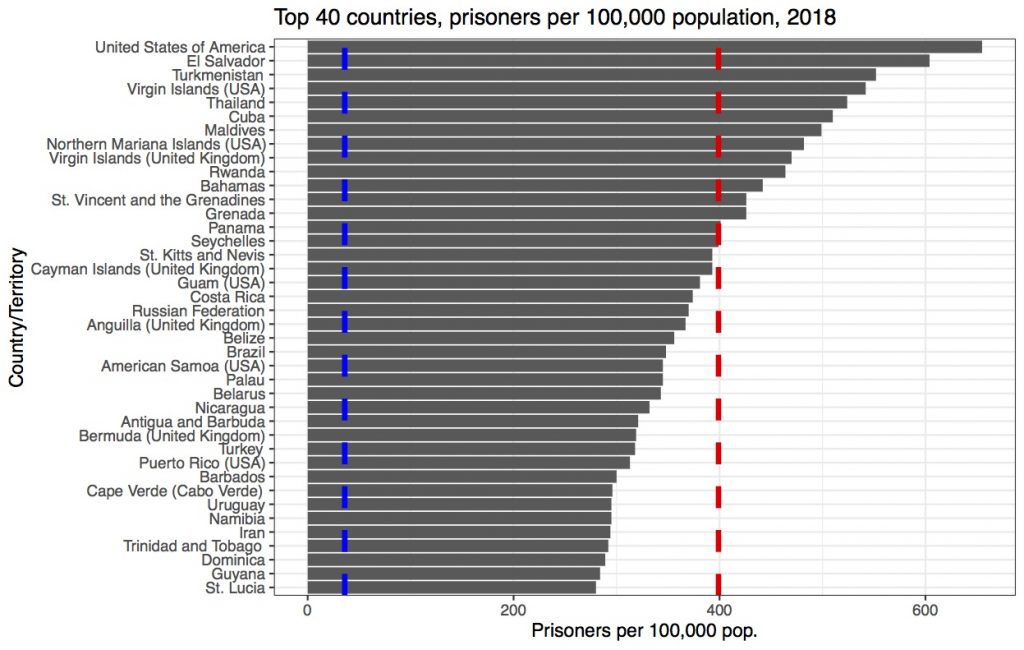

The US prison system was—and is still—known for incarcerating a disproportionately high percentage of its Black population. If we placed colonial Nigeria in a ranking of the top countries by incarceration rates today, it would come in at the 15th spot among the 222 countries with available data, and 3rd behind the United States and Thailand for countries with a population of at least 50 million, as shown in Figure 1. Nigeria today incarcerates a much lower share of its population, ranking in at 211 of 222 countries.

In colonial Nigeria, as part of explicit government policy, prison labor on government public works like roads and railroads was a mandated part of incarceration. Galvanized by the need to minimize the cost of spending on important public works projects needed to intensify exports of agricultural commodities and maximize revenue to the colonial government, colonial officials engaged in a number of cost-cutting measures involving forced domestic labor in the African colonies. Prison labor was one such cost-cutting measure. In fact, so valuable was this sort of forced labor to the functioning of colonial governments in Africa, that one official in 1911 (in stark echoes of another US prison official over 100 years later), lamented scaling back forced labor legislation as “how is the work of sanitation, road making and clearing to be carried on…[without] the necessary labour?”

The economic value of prisoners for the British colonial government is reflected in one of our paper’s key results: that the overall, gross value of prison labor or value of unpaid wages to African prisoners was strictly positive over the entire colonial period. Even after we account for the most expansive set of prisoner maintenance costs, like food, prison guard salaries, and prison equipment purchases, among others, the net value of prison labor was strictly positive in almost 60 percent of the years under study from 1920 to 1959. Prison labor was economically advantageous to colonial regimes.

This result had perverse implications for the way colonial authorities used incarceration to address sudden labor shortages that were endemic throughout much of colonial Africa. Agriculture was the major sector for both government revenues (over 70 percent customs and excise taxes from agricultural commodity exports) and African workers’ incomes in colonial Nigeria. So during “good” rainfall years, when agricultural productivity increased, this meant more income for both the colonial government and African workers.

On the other hand, it also meant that colonial governments had increased incentives to push forward construction on public works projects, like roads and the railroad, to intensify extraction and transport of agricultural commodities to the coast for export. The combination of severe labor shortages and a cost-minimizing colonial government with a taste for prison labor meant that more Africans were imprisoned during these “good” agricultural years.

In other words, positive economic shocks increased incarceration rates and the use of prison labor. The effect is reversed during Nigeria’s postcolonial period (beginning with independence in 1960), where prison labor was not a central part of state finance and policy (and though agriculture is still the major sector for GDP, over 75 percent of government revenue now comes from petroleum exports).

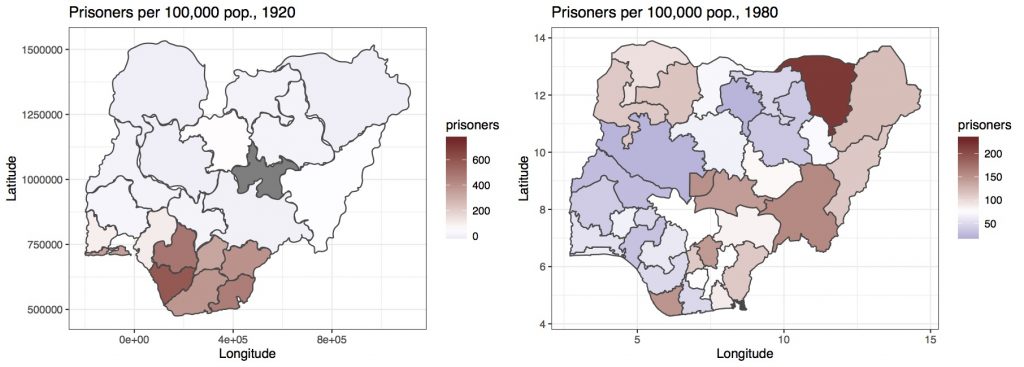

In the postcolonial period (with our data from 1971-1995), negative shocks like droughts or floods that decrease people’s agricultural incomes tend to increase incarceration rates, primarily through economic crimes like property theft. The reversal result and differences in the rationale of incarceration between colonial and post-colonial governments are reflected in the differences in the spatial distribution of prisoners between the colonial and postcolonial periods, as shown in Figure 2. Colonial imprisonment rates are higher and clustered in the southern region, which had more productive export cash crops like palm oil and cocoa than in the northern region. The picture for postcolonial imprisonment is much more dispersed/much less clustered in Figure 2.

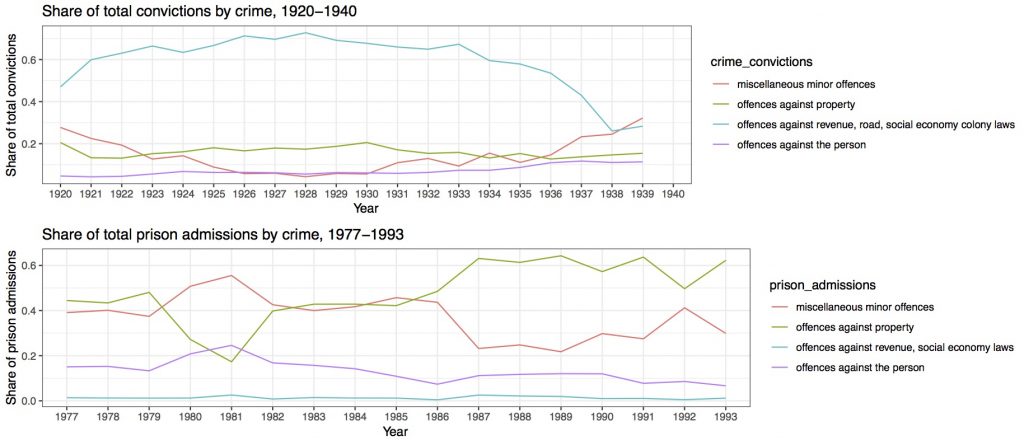

These differences are also reflected in the categories of crimes for which Africans were incarcerated during the colonial vs postcolonial periods, as shown in Figure 3. Over 50 percent of convictions in colonial courts were essentially for tax default and violations of colonial “social economy” laws (including everything from shirking an employer to ‘vagrancy’) or “offences against revenue laws, municipal, road and other laws relating to the social economy of the colony.” The major postcolonial period category for incarceration, on the other hand, is property crimes.

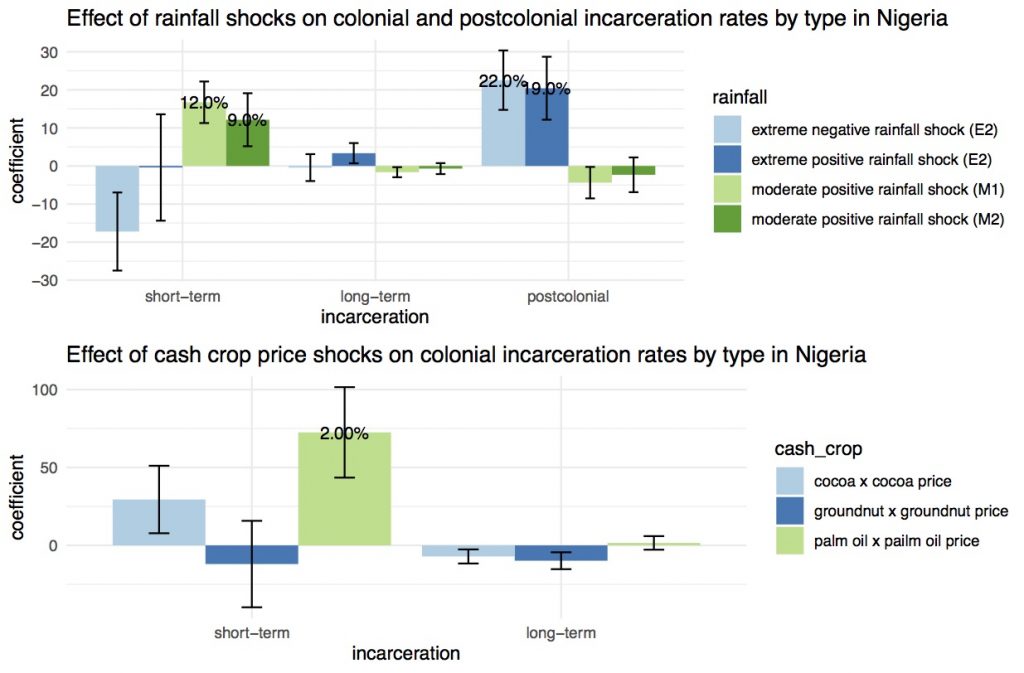

To add estimates to these results, we find that moderate positive rainfall shocks, signaling increases in agricultural productivity in a largely agrarian economy, increased short-term incarceration rates (for prisoners with less than 6-month sentences), by between 9 percent and 12 percent, relative to a sample mean of 135 prisoners per 100,000 population, as shown in Figure 4.

These shocks had no effect on long-term imprisonment (defined as prison sentences of more than 2 years). We also found that moderate positive rainfall shocks were positively correlated with the rate at which people awaiting trial were handed short sentences. In contrast, moderate positive rainfall shocks have no effect on incarceration rates in the postcolonial period. Instead, extreme negative and positive rainfall shocks like droughts and floods increase incarceration rates by 21 percent and 19 percent, respectively, relative to the sample mean of 105 prisoners per 100,000 population.

Figure 4 also shows these effects redefining economic shocks not as rainfall shocks but as an index of major agricultural commodity exports, like palm oil, cocoa, and groundnut. We find that for one of the most productive cash crops, palm oil, higher palm oil prices increased colonial incarceration rates in areas producing the crop. Positive economic shocks increased incarceration rates over the colonial period as colonial officials strove to satisfy increased demands for labor on valuable public works.

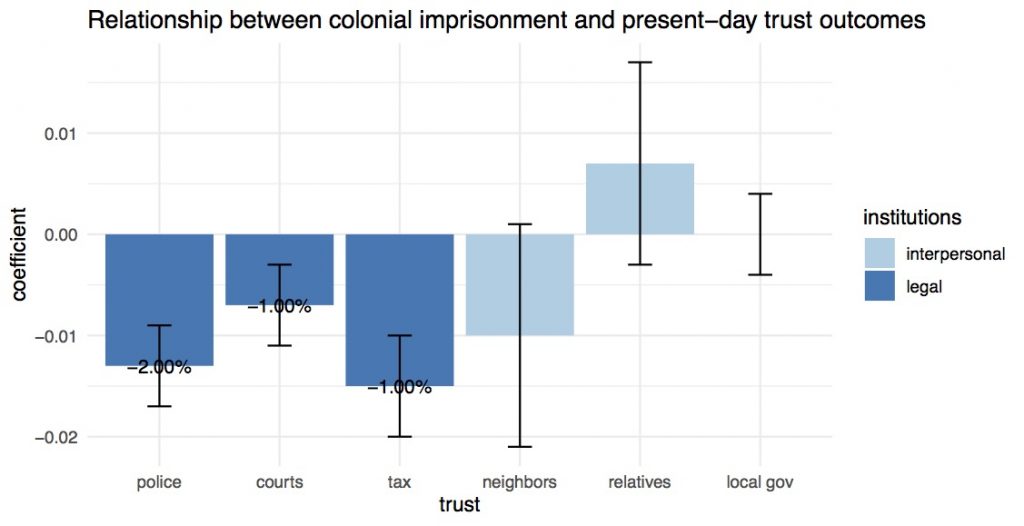

The data show that the use of prison labor by colonial regimes to satisfy economic and extrajudicial interests had long-term effects on citizens’ trust in legal institutions like police. And this trust is not easily restored. Despite Nigeria gaining independence in 1960 and the use of the prison system for economic interests ending shortly thereafter, contemporary trust in legal institutions, including police, courts, and tax administration, in areas with high historical levels of colonial imprisonment remain low, as shown in Figure 5. The mistrust is specific to legal institutions, and there is no effect of high historical levels of colonial imprisonment on measures of interpersonal trust, like trust in neighbors, relatives, or elected local governing council members.

Our historical research has implications for contemporary policy. While prison labor may seem like an attractive prospect for governments seeking to boost their economies in the face of rising prison populations, states should proceed with caution given the potentially negative effects on incarceration rates and citizens’ views of state legitimacy.