While big brands can afford to pause their addiction to Facebook, most advertisers cannot participate, as they have become so dependent on Facebook’s ad-targeting tools.

Is July’s advertiser boycott of Facebook a reaction to the ongoing pandemic, or the summer’s protests, or the upcoming autumn election? Yes.

According to the organizers’ public spreadsheet listing advertisers pledging to support the #StopHateForProfit boycott, nearly 1000 companies had signed on at the time of this writing. The list encompasses automakers (Acura) to jewelry retail (Zales) but reads like a who’s who of socially conscious companies.

Some members of the founding coalition leading the effort were invited to a meeting with Facebook executives on July 7, but it proved unproductive as the company emerged defiant and the civil rights groups deflated and disappointed. Even though Sheryl Sandberg expressed a preference for “listening” to civil rights groups and its internal audit rather than its boycotting customers, Mark Zuckerberg signaled that he would consider a key demand from the coalition and establish a senior vice president of civil rights. But he did not budge on the proposal to issue refunds to advertisers whose ads appear on hateful and unsafe content.

This Facebook boycott campaign harnesses the moment. In the absence of a highly functional democracy, civics and social justice become duties reluctantly adopted by corporates responding to market forces and public relations. When silence is assumed complicity, inaction is an action, thrusting brands into conflict. Commerce is unavoidably politicized among fractured and plagued publics.

It’s easy to be skeptical about the sudden rise of advocacy coalitions organizing and amplifying the #StopHateForProfit campaign that’s pressuring companies to withhold their spending on Facebook to force change. How does one challenge Facebook’s multi-sided market and data-driven cultural dominance? Perhaps perspective into the political economies of Facebook’s actual customers—advertisers—reveals the paradox of this particular revolt. Pressed to realize that their dependence on the platform further dissolves boundaries between their corporate responsibility and their bottom line, advertisers may be realizing that the precision-targeted marketing utopia they demanded has had dystopian downstream effects on civil society.

Why Facebook Takes the Blame

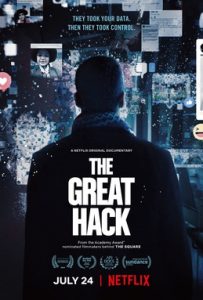

I appeared in Netflix’s The Great Hack (2019), which documents in vivid detail from the inside-out and outside-in why public animosity toward Facebook exploded in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election, epitomized by the Cambridge Analytica mass data abuse scandal. The film follows a former Obama campaign volunteer succumbing to the dark side and her escape, seeking redemption as she found herself writing up the first Cambridge Analytica campaign contract for Trump one moment to being subpoenaed by Robert Mueller’s investigation the next. In parallel, the film also tracks my own legal challenge from the outside-in, trying to pry open the mysterious company using transnational regulatory arbitrage in a quest to win full disclosure over my own political data profile. The filmmakers, through their filmography and public commentary, have drawn a line from the Arab Spring to the spring of Cambridge Analytica to this summer’s Facebook boycott.

Felt as a sudden lurch from unbridled tech optimism to cynical pessimism, perhaps anxious sentiments had been bubbling beneath the surface. The Cambridge Analytica scandal provided a spy thriller narrative with a striking cast of characters whose personal stories explained the new risks of an attention merchandising business that seems to dominate all aspects of society. It also illustrated the limits of transnational regulatory actions against a company that is often understood as its own sovereign state. Its power, accumulated through “growth hacking” network effects, is ruled by an invincible and unaccountable autocratic executive. An uncritical tech press cheered them on until the scandals that pierced our confidence in democracy started to erupt.

Today, as the US accelerates toward the 2020 election, two seismic events are rippling through all aspects of our lives. The Covid-19 pandemic not only exposes stark inequity while putting the economy on ice, it also reveals more of our collective unease with dominant technologies and their surveillance-based, politically-radicalizing business models. It pollutes the information space and incentivizes hyper-partisan and misinformation-laden chatter that politicizes public health measures and interventions such as vaccines, masks, and therapies.

The murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis ignited another simmering tension over America’s penchant for structural racism and militarized police brutality (also shamelessly and diabolically exploited on social media in 2016). Facebook groups host and monetize the user-generated content where the politics of pandemic and protest play out, mobilizing across the spectrum of conflict before they hit the streets and the balance sheets.

Facebook functions at the center of this turmoil, its product attracting, sorting, segmenting, mobilizing, and radicalizing, as it was designed. It turns out that the machine to sell skin creams is also good at selling extremism. Precise combinations of archetypes are modeled in Facebook’s ad-buying dashboard toward combinations of interest and identity selectors that narrow or expand an ad target size. But really, its proprietary unaccountable newsfeed and recommendation algorithms do most of the work optimizing engagement to maximize revenue and return on ad spending.

Facebook insists that it has enabled millions of small business owners to thrive. However, the ongoing boycott helps reveal how these businesses are largely dependent on Facebook, as Direct-To-Consumer (DTC) outfits cannot participate in the cultural backlash, even if it strains their ethical brand positioning. The relationship is feudal. While it may be true that micro-entrepreneurship blooms on Facebook, it may also be true that very few of these SMEs are independent of Facebook. Millions of companies are obliged to compete in the automated auctions that match eyeballs with propensities to convert to the highest bidder. The targeting and the reach available to direct response marketers on Facebook and Instagram are too effective to resist.

Observers of the industry, the journalists on the adtech beat, quickly noted that some advertisers pledging to back the boycott had not managed to pause all of their spending on lesser-known Facebook products such as its Audience Network, which targets ads off of its user-facing products, the blue Facebook app, and Instagram. Advocacy groups leading the charge will be called out when they decide to lean into the contradiction of spending money on Facebook ads to promote the boycott. Politicians calling for tough action against Facebook end up in a similar predicament, buying ads about how they would regulate or break up the company.

Lara O’Reilly sums it up best for Digiday readers by acknowledging that “[t]he effectiveness of Facebook’s targeting and huge reach are exactly what made the platform so attractive to advertisers in the first place.” Boycotting Facebook is hard.

“The vast majority of Facebook’s millions of advertisers are small businesses, serfs in the feudal scheme of monopoly platforms that sharecrop a field of attention, as users are harvested for their personal data.”

Why This Facebook Boycott Is Different

The grandiose paradox of Mark Zuckerberg’s imperial ambition to be at the center of everyone’s lives is that his company will be increasingly blamed for what ails us as a people. Deflecting regulators with lobbyists and journalists with comms flacks has worked effectively for Facebook, shielding its revenue and stock price through near-constant scandals since 2016.

But something is different about this month’s advertiser boycott. This is despite the fact that even when a constellation of multinational and household name brands assemble in resistance as titans of business in solidarity, they represent an inconsequential fraction of Facebook’s total ad revenue share.

The vast majority of Facebook’s millions of advertisers are small businesses, serfs in the feudal scheme of monopoly platforms that sharecrop a field of attention, as users are harvested for their personal data so that our susceptibilities can be rented out to mostly micro-advertisers chasing conversion rates.

Facebook was designed to be a platform-mediated marketplace distributing audience attention at wholesale prices in a few clicks. The hyper-targeted algorithmic newsfeed attracts users into targetable groups. Magnetizing users by behavioral ad targeting vectors lets small businesses arbitrage their sales transactions of direct-to-consumer conversions. Facebook’s dashboards drive entrepreneurs to merchandise their audience to their product, rather than the other way around.

Facebook might say it has enabled millions to build a small business such as targeting “Peloton Progressive Moms” who demonstrate propensities to engage with micro-targeted specialty skin creams in luxury packaging. The same interface also proves effective at getting these moms out to vote.

Unfortunately, the same platform appears effective at targeting skinheads with snake-oil supplements. Facebook has also been used in attempts to deceptively target Black voters for voter suppression efforts or for discriminatory employment recruiting. Clustering people into niche interest groups feeds the need to sell behavioral advertising.

There may not be an overt incentive to profit from hate, but it doesn’t matter if the platform was designed to automatically identify “Jew haters” as an ad targeting vector. It took journalists digging into the advertising dashboard to expose it, causing yet another public relations problem for the company. The category was removed. But this is what Zuckerberg’s machine was designed to do.

Even if both management and labor find all of this reprehensible, most advertisers on Facebook would run the risk of throwing themselves into bankruptcy protection by joining the boycott. The big brands can afford to pause their addiction to Facebook because their brick-and-mortar pre-Facebook equities equate to leverage here, especially when cost-cutting during pandemic-induced economic free fall is good business. These companies also rely on ads that signal brand equity rather than direct-response transactional marketing. Mark Zuckerberg reassures his staff that the big brands will be back “soon enough” while Sheryl Sandberg seems to assume that the company’s cherry-picking of its damming civil rights audit will pacify its critics, despite admitting that Facebook will never complete the task of fixing itself and will always have to “do more.”

Advertisers have found themselves in the awkward position of funding our tumultuous political life, whether it’s based on fact or fiction, diversity or discrimination, lockdown or re-open, masks or anti-masks, and anti-establishment zeal, whether it be from Black Lives Matter demanding criminal justice reform or ‘Boogaloo bois’ agitating for bloodshed. Despite enjoying surgical control of microtargeting on Facebook, all brands are at the mercy of Mark Zuckerberg’s sole authority to set and enforce policy that serves primarily to make his platform appear safe for society by making it attractive for advertising.

Simple slogans like #DefundThePolice and #StopHateForProfit may fail to articulate the complexity of the conditions they assail but are necessary tools of mobilization, a grammar of social media that demands hyper simplification as a means of hyper signification and memetic spread. Using toolkits for cultivating a brand, whether personal or corporate, means everyone is playing the game of merchandising attention, whether they’re an amateur, professional marketer, or full-time social media influencer.

The underlying mission of social media was always to make monetizers of us all by putting the tools and signals of digital marketing in everyone’s hands to achieve maximal scale and growth. A company’s economic imperative to eliminate perceived waste in their advertising was solved by Facebook’s privacy-eroding personalized media machine. But this implicates firms into the downstream effects on society. Now the paradox of advertising is everyone’s problem.

The coalition behind the boycott campaign has already succeeded in wielding the only weapon civil society has at its disposal precisely because it deploys the tools of attention arbitrage against the feudal rent-seeking power of Facebook, largely on Twitter. These activists know that Facebook’s sole vulnerability is losing control of its own narrative in the public’s eye, keeping Menlo Park’s formidable comms and policy teams on-call in damage control mode.

Multiple independent, organically emergent campaigns keep Facebook’s flacks on the defensive. For example, an anonymous campaign unaffiliated with #StopHateForProfit that goes by the pseudonym @Detox_Facebook succeeded at spreading a parallel and overlapping message through supercut videos optimized for Twitter virality depicting Facebook’s culpability in the unraveling of the world.

How the Facebook Ad Boycott Campaign Works

A key participant of #StopHateForProfit is Sleeping Giants, the formerly anonymous team of volunteers with backgrounds in marketing and adtech, insiders who know firsthand how the abstruse digital supply chain really works. They recognized the bind brands are in when they are caught subsidizing racist genocidal hate, toxic disinformation, anti-democratic disenfranchisement, child sexual exploitation and abuse, and worse. Whether it’s white supremacist propaganda or a reflexive disdain for facts and scientific expertise, the kind of flagrant and hyper-partisan falsification and fraud for which Facebook’s algorithm seems optimized, when it’s sponsored by consumer-packaged goods or franchise chains, it’s just not a good look.

The technique that Sleeping Giants’s co-founders Nandini Jammi and Matt Rivitz pioneered, which chased most of Breitbart’s advertisers away by tweaking their programmatic adtech, is also the core mechanic of this recent campaign. Branching off after a dispute, Jammi launched a new consultancy for brands reeling from the boycott’s fallout and the crisis of brand safety and ad fraud more broadly.

Rivitz brought the same playbook to the SHFP campaign. Originally, it worked as follows: Shame brands on Twitter, with screenshots of their ads monetizing hate serving as tagged receipts. Alerts on a social media manager’s dashboard trigger a corporate escalation. Sleeping Giants backchannels the industrial expertise to fix the adtech on the back end in order to remedy the situation by demonetizing and de-platforming bad actors otherwise injuring the brand. The free market at work.

The campaign evolves this method by force-multiplying with partner groups in advocacy and civil rights (Anti-Defamation League, Common Sense Media, NAACP, Color of Change, Free Press) to raise the stakes and pool pressure points. Twitter is the information battlespace because it’s where the brand managers, journalists, activists, policy wonks, comms people, marketing gurus, CMOs, academics, and celebrities spend their time and attention and wield amplification clout. It’s also a space liberated from Facebook’s grip on the attention economy. You can’t really succeed at being anti-Facebook on Facebook. But you can influence the influencers and change the conversation in the media more broadly on Twitter.

Consumers in the US, most of whom are likely voters, are mostly worried about the future and the direction of the country. Ad spending was already plummeting across categories as the market constricted, with consumers quarantined and lined-up for public benefits well before the Facebook boycott set in. Partisans were already head-locked in the dispute over whether freedom of speech means freedom of reach or whether Facebook and Twitter are raucous public squares or private clubs made wholesome for advertising. Even the George Floyd protests are imaginable as a sequel to the civil insurrections triggered in Ferguson, Missouri during the tense lead-up to Trump’s stunning capture of the White House, inflamed by adversaries and bad actors on Facebook as it was.

But even as lingering artifacts of the Jim Crow era are being purged from grocery aisles, state flags, and professional sports teams, uncertainty over an uncontrolled virus paralyzes the economy, while billionaires like Mark Zuckerberg capture even more wealth and political power. Advertisers may be caught in the middle, but this summer’s Facebook ad boycott taps into the mood of a world on the brink and certain only of change.

Top photo by Anthony Quintano, via Flickr [CC BY 2.0]