A new paper examines data on local outbreaks in South Korea and finds that even in the absence of lockdowns, an increase in confirmed infections of 1 per 1,000 people caused a 2-3 percent decline in local employment. This suggests that nearly half the job losses in the US may be due to private businesses and consumers voluntarily reducing their economic activity, rather than government-mandated lockdowns.

When will the global economy recover from the ongoing coronavirus crisis? The economy has been reopening for two months, but the unemployment rate was still at 11.1 percent in United States in June, dashing any hope that the economy would bounce back quickly once the lockdown measures were lifted.

Even worse, as the number of new cases in the US rises fast in the South and West, many local governments are pausing or backtracking on the reopening of the economy, implying that whatever gains in employment we had in May and June can quickly evaporate.

The stay-at-home orders by state and local governments obviously hurt the economy—a trade-off local officials made to slow the spread of Covid-19 cases and ease the burden on hospitals. However, with or without lockdown, an epidemic makes people hunker down and reduce economic activity for fear of infection.

Understanding how much of the economic downturn is caused by people’s voluntary reactions and how much is caused by lockdowns helps us answer two important questions. First, what is the course of the economic recovery after lockdowns are lifted? Second, how large are the additional economic costs that lockdowns cause? The latter is especially important for a cost-benefit analysis of government policies designed to contain epidemics.

In my research with Sangmin Aum and Sang Yoon (Tim) Lee, using South Korean data, we isolate the economic effect of Covid-19 that operates through the fear of infection: the voluntary reduction in economic activity in response to local outbreaks.

The South Korean government primarily relied on extensive testing and contact tracing, rather than a lockdown, to contain the epidemic. Our benchmark results use data through February; beginning in March, the government closed schools and recommended social distancing.

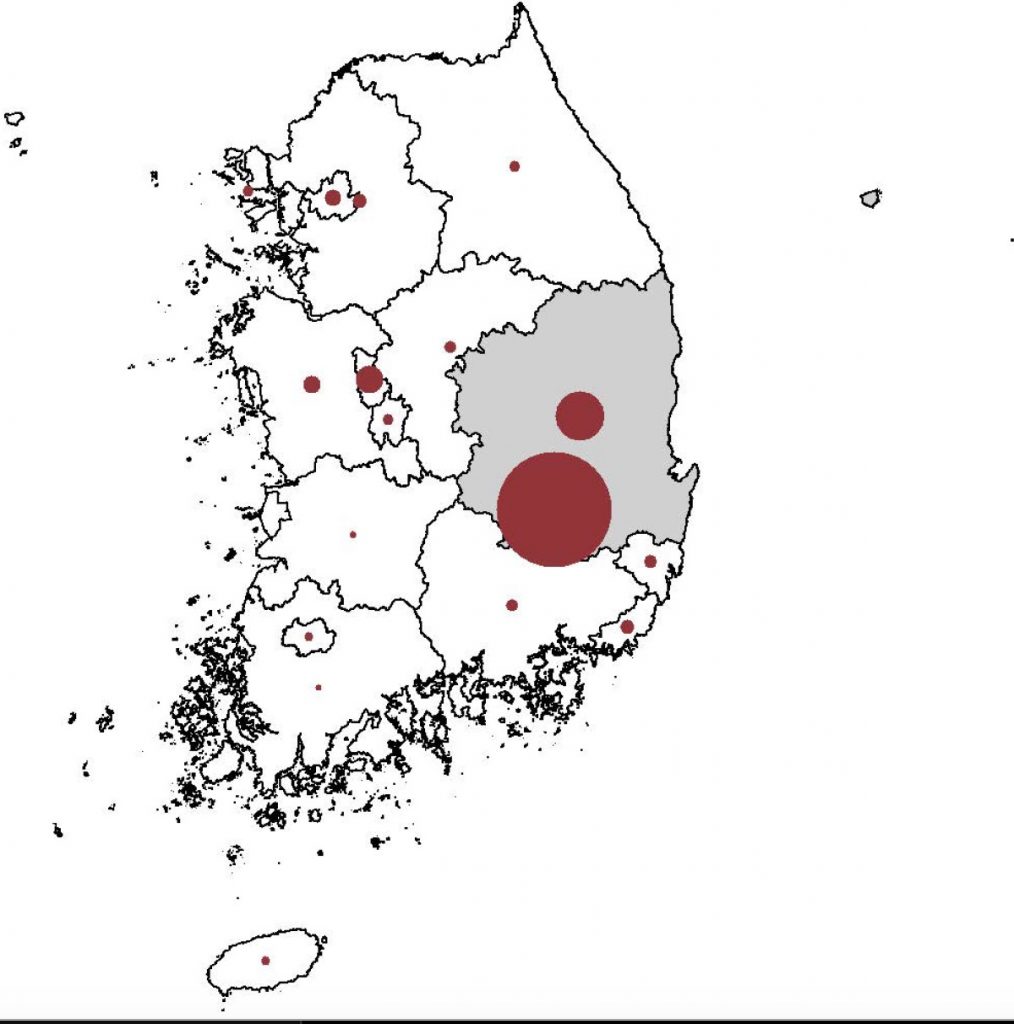

Our estimation takes advantage of the absence of mandatory lockdowns in Korea and the variation in Covid-19 outbreaks across regions that are uncorrelated with economic conditions. In South Korea, only one region, Daegu-Gyeongbuk, had a significant number of infections, traced to a religious sect. Of the 9,569 cumulative cases nationwide by the end of March, 83.4 percent were in Daegu-Gyeongbuk.

We establish that the Covid-19 outbreaks, not other concomitant factors, are the cause of the divergent economic outcomes between that region and the rest of the country.

We find that an increase in confirmed infections of 1 per 1,000 people causes a 2-3 percent decline in local employment in the absence of lockdowns. In comparison, in the US, which implemented large-scale lockdowns, a 1-per-1,000 increase in infections is associated with an employment decline of 6 percent, suggesting that nearly half the job losses in the US may be due to private businesses and consumers voluntarily reducing their economic activity, rather than a consequence of government-mandated lockdowns.

While it is an open question whether our estimate from South Korea can be directly applied to the US, it provides a unique reference point for the economic costs of the epidemic in the absence of a lockdown. In particular, it partially answers the two above questions about the course of economic recovery and the potential economic costs of lockdowns.

First, lifting the lockdown measures alone can bring back, at most, half the lost jobs. Unless the infection rates fall (which, in the US at least, has not been the case), people will not fully return to normal economic lives, even without a lockdown. These findings are consistent with the latest unemployment numbers and data on consumer spending in the US.

Second, lockdowns are implemented to contain the epidemic (or “flatten the curve”). Suppose that infection counts would have reached more than twice the actual US level had no lockdown been implemented. Since employment losses would be our causal estimate of 2 to 3 percent times the number of infections per thousand, the US employment loss would have been even larger. Indeed, with the number of new cases in the US rising rapidly in the South and West as a result of premature reopening, even the modest employment gains we had in May and June are in peril.

“Lifting the lockdown measures alone can bring back, at most, half the lost jobs. Unless the infection rates fall (which, in the US at least, has not been the case), people will not fully return to normal economic lives, even without a lockdown.”

This is not to say that lockdowns are the best policy response. They are a very blunt tool that causes more economic damage than necessary. In a companion paper, we use a more-theoretical approach and show that targeted policies can more effectively contain the epidemic at a lower economic cost.

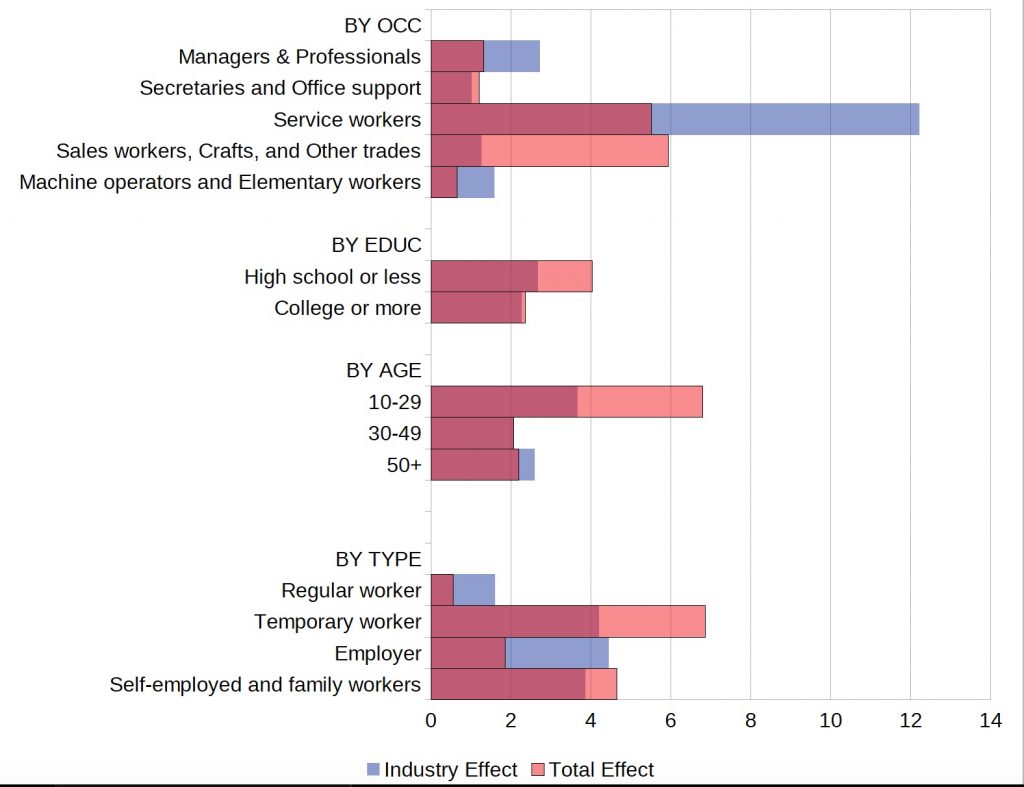

The second major finding of our study is that the negative economic impact of local Covid-19 outbreaks is not equally distributed across sectors, firms, and workers. This pattern is the same with or without lockdown.

By sector, the employment losses caused by local outbreaks are concentrated in the accommodation/food, education, real estate, and transportation industries. Consumers who are fearful of infections tend to avoid these contact-intensive industries even in the absence of a lockdown. These types of businesses are also the ones hit hardest in the US during the lockdowns.

Overall and within sectors, nearly all employment losses caused by local outbreaks were accounted for by small businesses with fewer than 30 employees. Large businesses in some industries, such as transportation/storage and information/communications, actually increased employment.

More alarmingly, the negative economic effect of local outbreaks in the absence of a lockdown was focused on socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. The job losses primarily fell on those with less education, the young, and workers on temporary contracts. Moreover, these groups were more vulnerable even within sectors, meaning that they did not just lose their jobs because they all worked at restaurants or hotels. They lost the most jobs within every sector.

These distributions of causal effects are similar to what we observed in the US and the UK during lockdowns. We conclude that the unequal effects of Covid-19 are the same with or without lockdowns.

Our analysis guides our expectations of the post-lockdown recovery. Lifting lockdowns will lead to only modest recoveries in employment unless infection rates are kept low for a sustained period. As of this writing, the number of daily new cases in the US is rising: People are not ramping up economic activities as they are still fearful of infections, and local governments are pausing or even reversing the reopening of the economy. All this means that the economic recovery will be weak and sluggish unless we bring the epidemic under control.

In addition, the fact that socioeconomically disadvantaged workers were harmed the most, even without a lockdown, means that lifting the lockdown will not improve inequality.

And if there were to be a second wave of the epidemic later this year or early next year, even if it doesn’t trigger a second lockdown, people will again curtail economic activity out of fear of infection, quashing any economic recovery to that point.

It is the virus, not lockdowns, that dictates the course of the economy. The best way to revive the economy is to eradicate the virus.

Yongseok Shin is a professor of economics at Washington University in St. Louis. Sangmin Aum is an assistant professor at Myongji University in Seoul, and Sang Yoon (Tim) Lee is a reader at Queen Mary University of London.

References

Aum, S., S. Y. T. Lee, and Y. Shin. “Inequality of Fear and Self-Quarantine: Is There a Trade-off between GDP and Public Health?” Working Paper 27100, National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2020.

Aum, S., S. Y. T. Lee, and Y. Shin. “COVID-19 Doesn’t Need Lockdowns to Destroy Jobs: The Effect of Local Outbreaks in Korea.” Working Paper 27264, National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2020.