Two years ago, the Morandi bridge collapse claimed 43 lives. Based on financial statements, Italian government documents, and interviews with independent experts and corporate executives, the Stigler Center case study explores the crisis management and lobbying strategy of Atlantia, the company that controlled the bridge, and how a well-connected company could pile up billions of euros in dividends and survive a major financial and reputational shock.

On August 14, 2018, millions of Italians were traveling on holiday just before “Ferragosto,” the annual midsummer celebration that takes place on August 15. Shortly before noon, a 656-foot section of the Morandi bridge in Genoa collapsed, causing 43 deaths and the evacuation of 566 people from their homes.

The disaster also seriously jeopardized the economy of one of the richest regions in Italy, because the bridge had linked the city of Genoa to the A10 motorway in France.

Who was responsible for the 43 victims? Many politicians and commentators immediately blamed Autostrade per l’Italia, the company that operated the bridge under a government concession.

In 1999, Iri, a state-owned financial holding company, sold a majority stake in Autostrade per l’Italia to the well-known and well-connected Benetton family. After three decades of success in the garment industry, the Benettons profited from the privatization process that the Italian government had to launch at the end of the 20th century to curb its unsustainable public debt.

Despite their lack of expertise in infrastructure, the Benettons bought 30 percent of the shares of Autostrade for less than €2.5 billion, thanks to their connections with Italy’s center-left parties. In the next five years, the Benettons increased their share in Autostrade to 84 percent, thanks to a leveraged buyout.

Despite the burden of more than €6 billion in debt due to the leveraged buyout, five years after its privatization, the market capitalization of Autostrade was €11.3 billion. Today, the Benettons control Autostrade through a financial holding company called Atlantia. Between 2000 and 2008, Atlantia paid €11 billion in dividends to its shareholders.

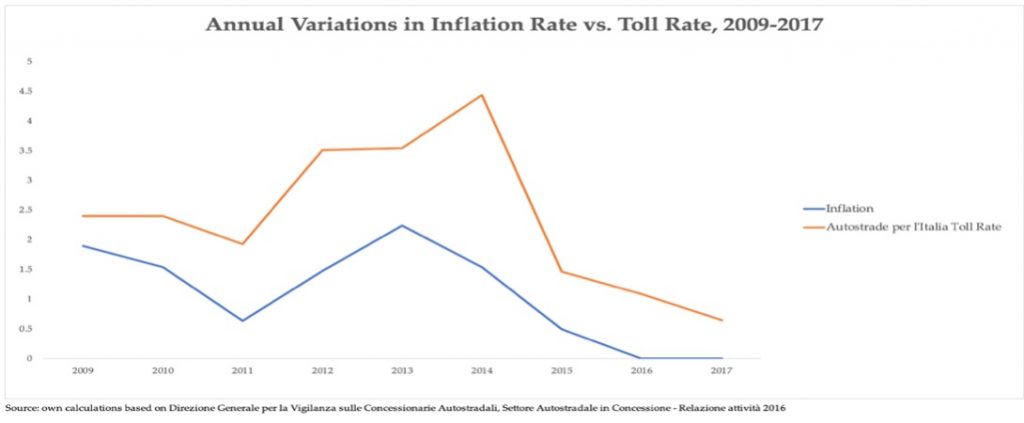

The highways proved to be the perfect rent for the Benettons: every year since the privatization, tolls grew faster than inflation, despite the lack of investments.

Is there any link between the Benettons’ rent-seeking behavior, Atlantia’s profits, highway regulation, and the bridge collapse? A new Stigler Center case study explores the risks of regulatory capture, the importance of the media, and how powerful corporations can foster connections with political parties, regardless of ideology.

The case was written by Guy Rolnik, a clinical professor of strategic management at Chicago Booth, along with Sara Bagagli, a graduate student in economics at the University of Zurich, and Stefano Feltri, the editor of the Italian newspaper Domani and a former editor of ProMarket.

After the 2018 tragedy, the coalition government supported by the leftist populists of the Five Star Movement and the right-wing nationalists of the League announced its intention to revoke the concession to Autostrade per l’Italia. One year later, on July 1, 2019, a committee of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport concluded in an advisory opinion that Autostrade was in “non-fulfillment of custody.”

A few weeks after the ministry report, three employees of companies owned by Atlantia were arrested for omitting relevant information and falsifying safety reports. Atlantia CEO Giovanni Castellucci eventually resigned. However, more than two years after the Morandi bridge collapse, the Benettons have managed to preserve the highway concession, despite the ongoing criminal investigation.

Autostrade denied any wrongdoing. It agreed to pay €439 million to rebuild the bridge [which was ultimately demolished in 2019], but the company also sued the government for excluding it from the reconstruction process.

Thanks to a decade-long lobbying effort, the concession contract with the government is so favorable to Autostrade that the company can claim up to €20 billion in case of early termination. Even if the early termination is due to Autostrade’s failure to meet its obligations, the payment is reduced by only 10 percent. The details of the contract were classified until the Morandi bridge collapsed.

Based on financial statements, Italian government documents, and interviews with independent experts and corporate executives, the Stigler Center case study explores Atlantia’s crisis management and lobbying strategy, and how a well-connected, family-owned company could pile up billions of euros in dividends and survive a major financial and reputational shock.

The Atlantia case is designed for courses focused on corporate governance, non-market strategies, media and business, crony capitalism, and regulated industries. The Stigler Center will provide teaching notes to professors interested in the case. Read it here.