A new paper seeks to examine whether police misbehavior is concentrated or diffuse by identifying whether highway patrol officers in Florida are more lenient towards white drivers than minority drivers when issuing speeding tickets.

In response to the tragic murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers, protesters throughout the country have demanded changes to a policing system that they see as discriminatory towards African Americans and Hispanics.

Policy debates over police misbehavior often focus on the question of whether undesirable conduct is confined to a “few bad apples” or is systemic throughout the force. Answering this question is crucial for identifying the best policy response. While a targeted policy of disciplining or firing a few problem officers may work well in a “bad apples” scenario, such approaches will be ineffective if misbehavior is more pervasive.

In a recent working paper, we shed light on whether police misbehavior is concentrated or diffuse by examining discrimination on the part of individual police officers. We study speeding enforcement by the Florida Highway Patrol. Our aim is to identify whether officers are more lenient towards white drivers than minority drivers when issuing speeding tickets.

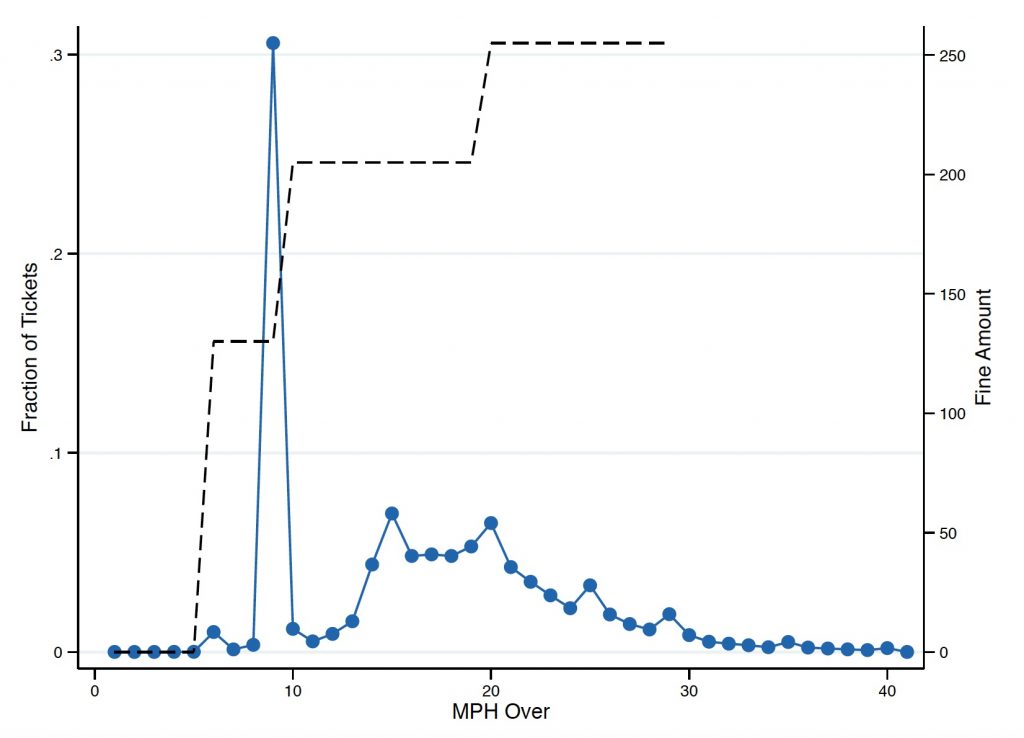

As in most states, the fine for speeding in Florida jumps at certain speeds. The fine for driving 6-9 mph over the posted limit is about $125, while the fine for driving 10-14 mph over the limit is about $200. Anecdotally, a common practice among officers is to give drivers a break by issuing them a ticket for a lower speed. For example, a driver may be stopped at 13 mph over but have their ticket list a speed of 9 mph over, resulting in a $75 fine reduction.

When we plot the distribution of raw speeds in our data, we find that over 30 percent of all tickets are issued for 9 mph over the limit, just below the first large fine increase. Fewer than one percent of all tickets are issued for 8 or 10 mph over the limit. The substantial spike in the distribution of tickets suggests that officers are regularly giving a break to drivers.

An alternative explanation for the observed bunching is that drivers are responsible. Drivers may know about the jump in fine and set their speed just below the fine increase. However, we find a significant spread in behavior across officers, with some officers writing a majority of their tickets at 9 mph and some with almost no tickets at 9 mph. This variation across officers indicates that the bunching of tickets is due to officer discretion rather than driver behavior.

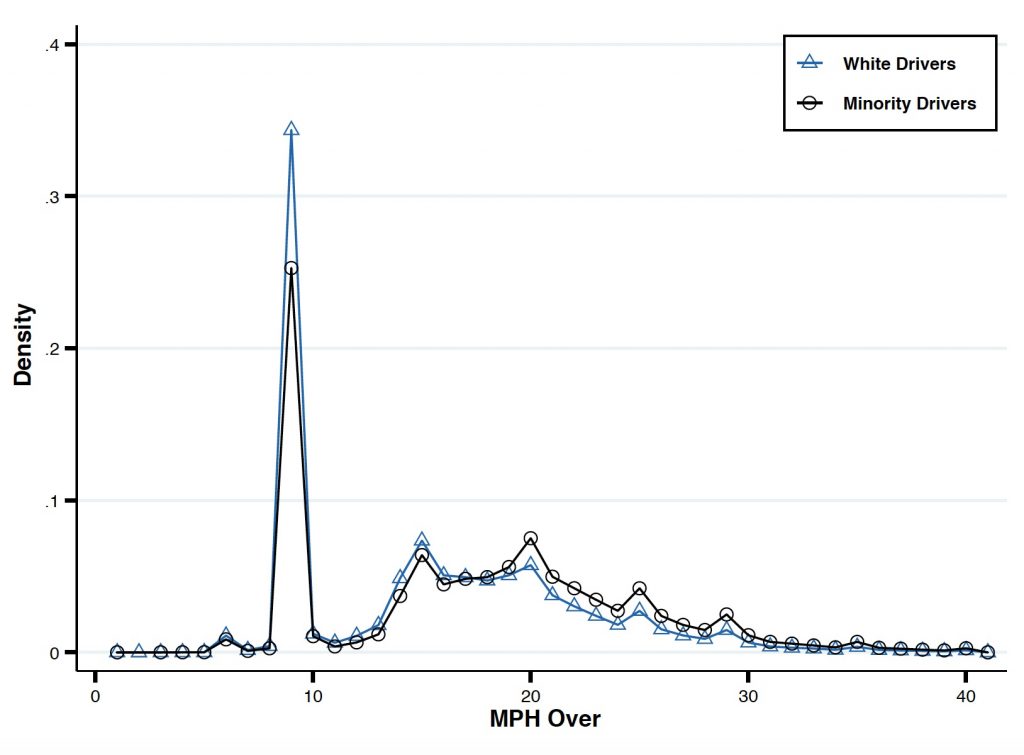

When breaking our data down by the race of the driver, we find that white drivers are issued a ticket at 9 mph 34 percent of the time and minorities are issued tickets at this speed only 25 percent of the time. Some of this gap can be explained by where drivers of different races are being stopped. For example, black drivers are disproportionately likely to be driving in Panhandle counties, where officers are less lenient towards all drivers. However, a disparity of about 6 percentage points persists even when comparing white and minority drivers stopped in the same county at the same time of day.

A central challenge of our study, and of all studies on discrimination, is to rule out that race is correlated with some behavior that is not recorded in the data but is generating the disparities in treatment we observe. In our setting, for example, minority drivers could be driving faster than white drivers. If officers are only lenient towards drivers whose speeds are close to 10 mph over, they may be disproportionately generous to white drivers.

To address this concern, we rely on the fact that about one-third of officers in our data practice no lenience—their ticketed speed distributions exhibit no bunching at 9 mph over the limit. These officers write a similar number of tickets as their lenient colleagues and stop similar drivers in terms of demographics. We use these non-lenient officers as a “speedometer” to estimate the underlying distribution of ticketed speeds absent any manipulation by officers.

Using this approach, we find some evidence that minority drivers are stopped at slightly higher speeds. However, the difference is quite small and insufficient to explain the gap in treatment between races of drivers, which we conclude is due to discrimination on the part of officers rather than differences in driving behavior.

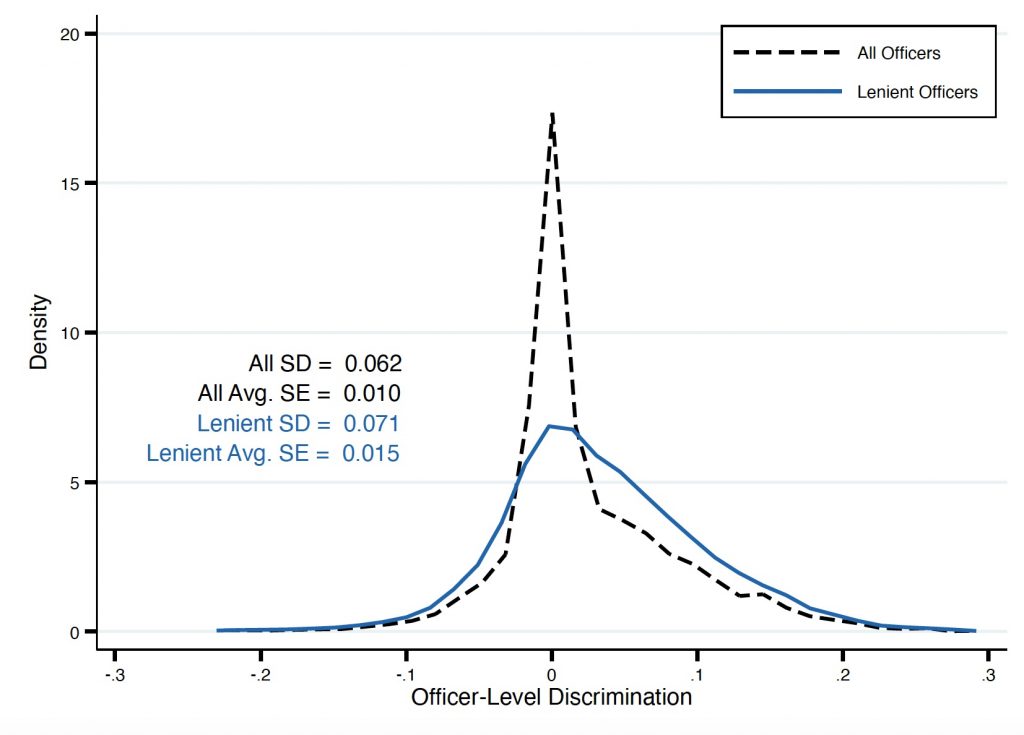

A key strength of our setting is that the average officer writes hundreds of tickets over a several-year period. The high frequency of recorded activity allows us to adapt our empirical approach to estimate the degree of discrimination for each individual officer. Doing so, we find that 40 percent of officers practice discrimination. While this figure is not the majority of officers, it is hardly a few bad apples.

As we noted above, understanding whether discrimination is concentrated or widespread is necessary for choosing the appropriate policy response. In our setting, we find that removing the most discriminatory 5 percent of officers does very little to reduce the total disparity in treatment because these officers only comprise a small share of all discriminatory officers.

Furthermore, hiring more minority and female officers does little to narrow the gap in treatment. However, reassigning officers so that neighborhoods with the most minority drivers are staffed with more “lenient” officers can lead to a nearly complete removal of the gap in treatment.

While understanding the extent to which misbehavior is concentrated within a police force is important for designing an effective policy response, it is important to note that even a small share of problem officers can cause significant harm to society. As comedian Chris Rock argued, some jobs, such as airline pilots, are too important to allow any bad apples.