Just like Spotify, Apple has amassed an installed base of users. Spotify sells its users to advertisers while Apple sells its users to app developers. What is the right way of doing that, and how should we think of Apple’s 30 percent commission? The 1969 US antitrust case against IBM offers valuable lessons.

Last week, the European Commission launched two investigations into Apple regarding iOS. The first focuses on the App Store and whether Apple is distorting competition for music streaming and distribution of ebooks and audiobooks, while the second is focused on whether Apple is impermissibly limiting competition with Apple Pay. Both of these investigations are part of a broader look at digital marketplaces ongoing in Europe, the United States, and most of the world.

To understand how we reached this point, we should backtrack a little. On March 13, 2019, Daniel Ek, the founder and CEO of Spotify, announced in a blog post that Spotify had filed a complaint with the European Commission, as Spotify believed that Apple was using its control over iOS to compete unfairly with Spotify in the music streaming market.

Streaming has revitalized the market for paid recorded music, which before then had been in a steep two-decade decline.

Spotify runs a freemium business model. You can listen for free, but if you do that, just like old-time over-the-air radio, you will pay by listening to ads. This is a standard two-sided business model, where a broadcaster—in this case, Spotify—assembles consumers to sell to advertisers.

Advertisers, of course, don’t expect to reach those listeners for free, and they pay Spotify for that right, roughly €217 million in 2019. But if Spotify users get tired of the ads, unlike classic radio, they can chose to dump the ads by switching to Spotify premium. That goes for $9.99 per month, though there are a number of bundles and plans.

Spotify’s 2019 revenues for premium were €1,638 million. That is where the real money is, and that makes converting a free customer into a paying one especially important for Spotify. At the end of 2019, according to the company’s reporting, Spotify had 153 million, ad-supported monthly active users (MAUs), as it puts it—I am one of those—and 124 million premium subscribers. Spotify competes with, among others, Amazon, YouTube, Pandora, Tencent, and, of course, Apple.

And it is the competition with Apple that gave rise to Spotify’s March 2019 complaint. Spotify pays nothing to Apple when a new user downloads the Spotify ad, as Apple collects nothing from advertising-supported apps. But at the point that a user converts from being a free customer to a paying customer, Apple wants to collect money.

The amount collected depends on the circumstances but ranges between 15 percent and 30 percent of the subscription fee. Apple doesn’t collect if a user signs up for Spotify premium outside the app, but to boost the chances of Apple getting paid, Apple has historically insisted that a user have the chance to make the purchase from inside the app and has limited the ability of the app developer to try to direct the user outside of the app to make the purchase.

Note that Apple doesn’t charge a different commission depending on whether it has a competing app. If you want to play Monopoly on your iPad, you pay $3.99 and Apple gets 30 percent of that and that fee has nothing to do with whether Apple does or does not have its own competing game of Atlantic City real estate domination. How some of this works exactly may be negotiable if you are, say, Netflix or Amazon, but the 30 percent fee doesn’t target any Apple competitor in particular.

“Don’t think of it as a 30 percent fee on the single transaction that turns into a paying customer for Spotify but think of it as a way of capturing charges to Spotify for all of the Spotify customers who have used Apple’s services to get the Spotify app.”

There is a basic question here: how should Apple get paid? Just like Spotify, Apple has amassed an installed base of users. Spotify sells its users to advertisers while Apple sells its users to app developers. What is the right way of doing that? Spotify wants to get paid by advertisers—and does, of course—but how should Apple charge developers for access to its users? And how should we think about the 30 percent fee? Rep. David Cicilline (D-RI), the chair of the House antitrust subcommittee currently investigating digital marketplaces, expressed views on this last week, calling the figure “unconscionable” and “highway robbery.”

These are old questions. In 1969, when the United States brought its Titanic antitrust case against IBM, the complaint was that IBM was bundling together hardware, software, and services, and in so doing was engaging in monopolization. IBM faced weak competition in the mainframe computer market and in not charging separate prices for services and software, the government believed that IBM was blocking competition in the adjacent services and software markets. Six months into the lawsuit, IBM announced that it was unbundling and that it would move to separate charges for services and software. Even though the government had achieved one of its key objectives in bringing the case, the lawsuit continued for another 13 years before the government dismissed the case in 1982.

So what should Apple do here? Should Apple build all of its charges into the price of the devices, just like IBM originally did for mainframe computers? And if so, does that mean Apple collects only when it sells a device? Should Apple stay out of the music streaming market, or should it compete in the market and charge for music? Can it also collect money when it acts, as it were, as a wholesaler facilitating sales by third parties? And should Apple, unlike Spotify, just give away—set a zero price—to software developers for access to the customer base that it has amassed?

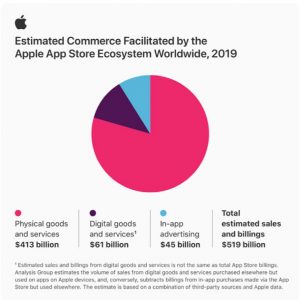

Before addressing those questions, we should consider one more bit of information. Either by plan or by luck, on June 15 Apple released a report on how it sees the value of the iOS ecosystem. Here is the key graphic from the report:

I don’t know whether those figures are correct, but I am most interested in the three separate categories of activities. Apple doesn’t charge a commission for activities in Categories 1 or 3, and only charges for activities in Category 2. Category 1 includes my pick-up orders from Walmart during the pandemic. Sometimes I do those orders on my Windows 10 laptop, sometimes on my iPhone, and I pay with my Amex card. Apple collects nothing in connection with that. It is handy to use my iPhone for my Walmart order, and I check in on it at Walmart when I get there, but there is nothing particularly intrinsic to the iPhone for this transaction.

But there are other activities where the smartphone really is deeply connected to the transaction. You could just listen to Spotify on your laptop, but lots of people don’t have personal computers and that would be a pretty limited way to engage with Spotify. I listen to Spotify in the car. I have the ad-supported Spotify app on my iPhone and Apple collects nothing in connection with that, as that is a Category 3 activity.

As Apple emphasized in its public response to the March 2019 Spotify blog post, the Spotify app has been downloaded from the App Store more than 300 million times and Apple was paid nothing.

There are really good reasons that you might want to have a “free now, pay later” approach to apps. Apps really are experience goods. They are zero marginal cost goods so, unlike physical goods, it really costs nothing to let you try them a bit before deciding whether you want to pay for them. Spotify’s freemium model takes that one step further in making it possible never to pay cash for the service, and Apple doesn’t collect then.

The 30 percent royalty rate has to be understood not just in the context of where a customer adopts the premium service but also as the point of compensation for the large number of Spotify customers who just use the free service and for whom Apple has provided services to Spotify but has never collected anything, even though Spotify is collecting from the advertisers. Don’t think of it as a 30 percent fee on the single transaction that turns into a paying customer for Spotify but think of it as a way of capturing charges to Spotify for all of the Spotify customers who have used Apple’s services to get the Spotify app.

I have focused on just one piece of the first EC investigation but let me tie this analysis to the second investigation. Recall that the EC is looking at whether Apple is artificially boosting Apple Pay. The idea here is that Apple is blocking other firms from using a piece of the iPhone hardware and iOS software—something called near field communications (NFC)—that makes possible tap and go payments using your iPhone. With the move to contactless transactions, the EC is understandably interested in how competition emerges in this market.

These types of interconnection issues are old ones in antitrust and network industries. I think that those are complicated—you can read my recent House statement in the digital marketplace investigation if you are interested—but I want to focus here on the tie back to the discussion of payments and where Apple should collect money. Uber is in Category 1 in the Apple graphic. Smartphones have made possible the ride-hailing market, but Apple doesn’t collect for those transactions. The wrinkle, of course, is that Apple does collect if you pay for your Uber ride using Apple Pay and that would be less likely if other firms had access to the NFC technology.

Payments in hardware, software and service ecosystems are pretty tricky. That really does go back at least as far as the 1969 IBM case. When IBM wasn’t charging for software, there was lots of software sharing, and IBM encouraged that to build demand for its mainframe computers. Software is a zero marginal cost good, so there are virtues to having a price of zero for it if you figure out someplace to collect for the costs that go into it. The European Commission doesn’t seem particularly concerned about these issues, a point that I have made here before in a prior discussion of the EC’s actions against Google’s Android.

There is much, much more to say about this situation and I have just scratched the surface. To just pick one issue, I have said nothing about data. There is a data issue in the app store case that is worth some analysis, but we are likely to get lots of chances this summer to consider data. Data is a key issue in the possible Google/Fitbit merger—and be sure to look at the preliminary analysis released on June 18 by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission—and it will almost certainly be an issue in an expected action by the European Commission against Amazon, so we can do data another day.