A new study suggests that the Payroll Protection Program’s funds were primarily allocated based on 2019’s estimated payroll, which is how the program was essentially designed.

As a response to the Covid-19 pandemic, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. The Payroll Protection Program (PPP) is one of the main policy responses in the act.

The PPP is designed to provide funds to help small businesses cover payroll and other expenses for eight weeks during the pandemic. As part of the first phase, the PPP received $349 billion of funding, and after rapid depletion of these, an additional infusion of $310 billion on April 24.

Despite being allocated approximately $660 billion in total, there have been two substantive concerns: (1) whether the PPP is sufficiently funded to meet the demands of small businesses and, (2) whether the funds are being allocated according to the design of the program.

In a new working paper, we provide insight into these two concerns. Overall, we find that PPP funds were primarily allocated based on payroll, which is what the program was designed to do.

The primary directive of the PPP is to allow any US-based small business to qualify for payroll relief. Specifically, qualified small businesses can request 2.5 times their average annual payroll costs.

A firm can request a maximum of $10 million, with the constraint that the eligible annual wages for any single employee considered in the payroll costs cannot exceed $100,000.

We use the program rules and publicly available payroll data to develop a simple model to estimate the potential magnitude of PPP requests in total and cross-sectionally by state, industry, and firm size. We then compare our estimates with actual PPP allocation data to examine how funds have been distributed.

We map the set of rules to publicly available payroll and tax data to derive an upper bound PPP request estimate by industry, state, and firm size. We estimate that total claims could reach up to $750 billion, but view this as an unlikely high-water mark.

“Overall, we find that PPP funds were primarily allocated based on payroll, which is what the program was designed to do.”

The payroll data allow us to make predictions not only in the aggregate, but also by state, industry, and firm size. Our analysis of deviations of actual allocations from predicted suggests that PPP funds have been allocated in a manner consistent with the model’s underlying assumptions based on the program’s rules. That is, the PPP funds have been allocated based on firms’ payroll.

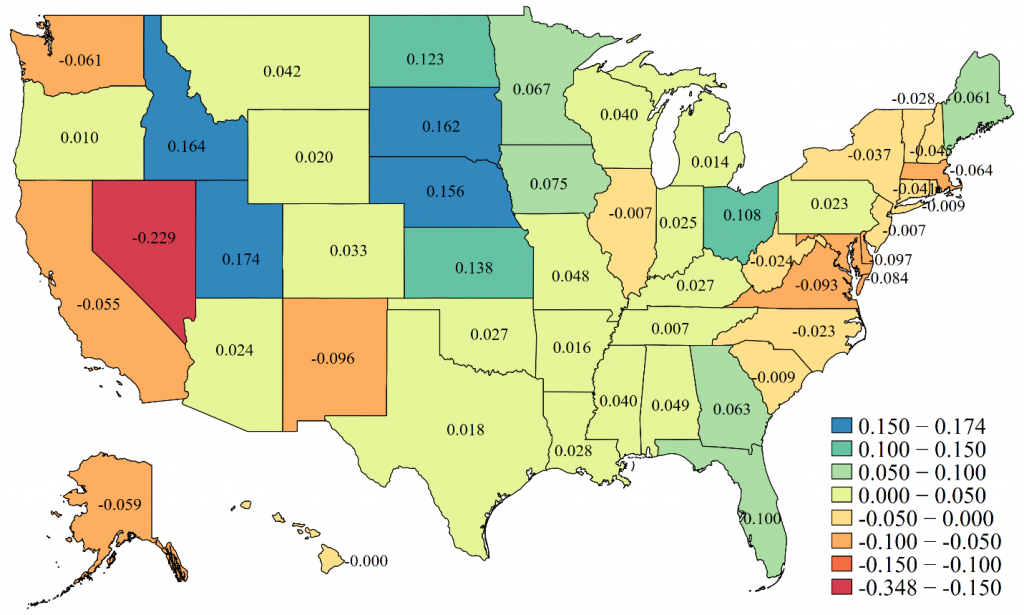

First, the prediction errors across states of the first round of funding were generally offset by the prediction errors of the second round. For example, New York and California received less than predicted in the first round, but more than predicted in the second. The prediction errors over both rounds are detailed in the map below. After the District of Columbia, Nevada has the highest error, being under-allocated relative to our prediction by 24 percent.

Over allocations are concentrated in Utah, Idaho, and the most eastern line of states in the Midwest, though some of these differences are due to agricultural business eligible for PPP but not in our baseline prediction.

Second, the first round of funding showed that the Manufacturing and Construction industries received more than expected, while the Professional Services and Health Care industries received less.

The SBA has not reported the second-round allocation by industry; however, preliminary analyses suggest that this industry disparity reversed in a similar manner.

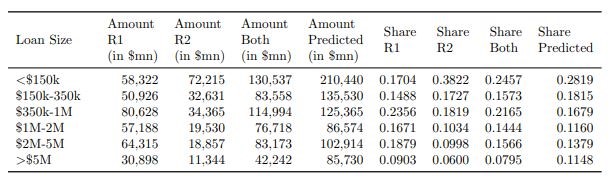

Third, analyzing the actual allocations by firm size is difficult because the SBA has only reported allocations by loan size and not firm size. However, our findings reveal that both tails of the firm size distribution appear to have been under-allocated relative to predictions.

The deviation for the largest firms is particularly apparent in the second round of funding, which suggests that pressure on larger companies to return funds or to not apply had an effect.

In sum, our findings suggest that the PPP funds were primarily allocated based on 2019’s estimated payroll, which was how the PPP was essentially designed. As such, the extent to which other possible objectives were not met (such as targeting certain regions, specific firm sizes, or particular industries more intensively), the issue is likely more the result of how the program was initially designed and less with how the program was ultimately carried out.