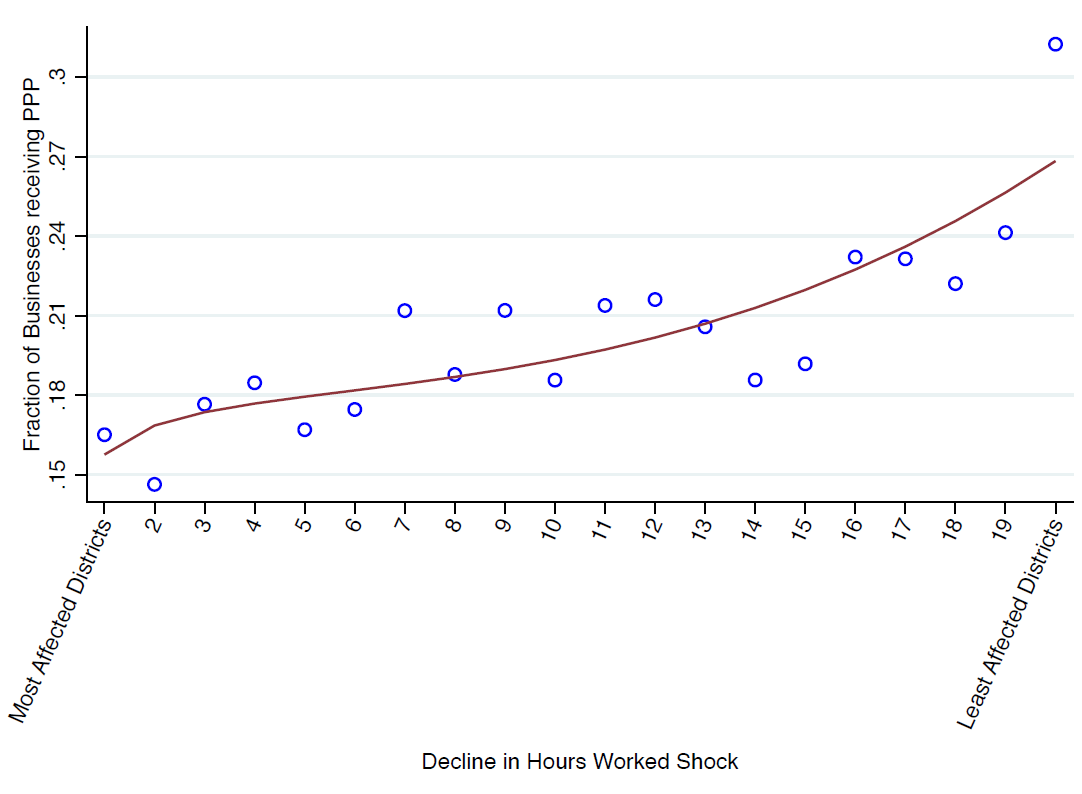

A new study shows that CARES Act funds to support small companies and prevent mass layoffs did not flow to areas more adversely affected by the pandemic. For example, 15 percent of establishments in the regions most affected by declines in hours-worked and business shutdowns received funding. 30 percent of the establishments that received funding are in the least affected regions.

The Covid-19 pandemic has triggered an unprecedented economic freeze as a result of the national containment policy. Among the firms most affected are the millions of small businesses, particularly in the retail and hospitality sectors, that depend on foot traffic and do not have access to public financial markets to manage short-term shocks to supply.

Without an existing system of social insurance to support these firms, policymakers rushed to develop new programs to contain the damage, culminating in the CARES Act and the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP).

In our recent working paper, we consider two dimensions of the PPP’s targeting. First, did the funds flow to where the economic shock was the greatest? Given that part of the policy objective was to prevent mass layoffs and firm bankruptcies, the potential benefits of the program are greatest in the areas that were hardest hit.

Second, given that the PPP program uses the banking system as a conduit for providing access to credit for firms, what role did banks play in mediating policy targeting? To build effective mechanisms for social insurance, policymakers need to understand how the existing infrastructure mediates the policy intervention and its pass-through to the affected groups.

The PPP began on April 3, 2020, as a temporary source of liquidity for small businesses (generally under 500 employees), authorizing $349 billion in forgivable loans to help small businesses pay their employees and additional fixed expenses during the Covid-19 pandemic. While firms apply for support through banks, the Small Business Administration (SBA) is responsible for overseeing the program and processing the loan guarantees.

The loans are forgivable under two conditions. First, the loan proceeds must be used to cover payroll costs or most mortgage, interest, rent, and utility costs over the eight-week period following the provision of the loan. Second, employee counts and compensation levels must be maintained.

Any companies that lay off workers or cut compensation between February 15th to April 26th have the potential to restore their standing by returning to their original employment levels and compensation.

We recently undertook a preliminary analysis of the PPP program and its effects on small businesses. We obtained confidential data from the SBA, containing information on the amounts and number of loans approved by each lender, amounts and number of loans received by small businesses in each state, and total amounts and number of PPP loans received by small businesses in each congressional district as of April 15, 2020.

We hand-match this data with the Reports of Condition and Income filed by all active commercial banks as of the fourth quarter of 2019, matching 4,228 of the 4,980 distinct participants in the PPP program to the Call Reports data.

We also draw on data from HomeBase, which is a technology company that provides scheduling services to many small businesses throughout the United States. These data have also been leveraged by Bartik, Bertrand, Lin, Rothstein, and Unrath (2020) to study the employment and hours outcomes of workers in the retail and hospitality sectors.

We find that lender heterogeneity in PPP participation is one major potential explanation behind the weak correlation between economic declines and PPP lending.

For example, consider the case of Wells Fargo. Because of an asset cap restriction that was in place since 2018, Wells Fargo disbursed a significantly smaller portion of PPP loans relative to their market share of small business loans. While the four largest banks in the US account for 36 percent of the total number of small business loans, they disbursed less than 3 percent of all PPP loans.

Our paper constructs a measure of which banks were most exposed to the PPP—which we call PPP Exposure (PPPE).

Figure 1 shows a scatter plot of the fraction of small business establishments receiving a PPP loan and the state exposure to the PPPE based on the number of loans.

The fact that lenders were significantly heterogeneous in accepting and processing PPP loans would not necessarily result in aggregate differences in PPP lending across geographic areas if small businesses could easily substitute and place their PPP applications to lenders that were willing to accept and quickly expedite them.

If many lenders, however, prioritize their existing business relationships in the processing of PPP applications, firms’ pre-existing relationships might determine to a large extent whether they are able to tap into PPP funds. In this case, the exposure of geographic areas to banks that over/underperformed in the deployment of the PPP might significantly determine the aggregate PPP amounts received by small businesses located in these areas.

Next, we examine if geographic areas that were exposed to banks with weak PPP performance received less PPP lending overall.

We do not find that funds flowed to areas that were more adversely affected by the pandemic, which we measure using declines in hours worked and business shutdowns. In some cases, we find that funds flowed to areas that were not hit as hard. For example, 15 percent of establishments in the regions most affected by declines in hours worked and business shutdowns received PPP funding, whereas 30 percent of all establishments received PPP funding in the least affected regions (see Figure 2).

In sum, our results highlight the importance that banking institutions play in mediating the effect of policy interventions. For example, if small businesses in a particular location do not have lending relationships with banks or the banks are not able to process the loans fast enough, then these businesses might be unable to obtain loans quickly enough.

These constraints in the existing infrastructure “tie the hands” of policymakers in some capacities, highlighting the importance of understanding how banking relationships play a role in affecting real economic activity.

Joao Granja is an Assistant Professor of Accounting at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Christos Makridi is a Research Assistant Professor at the W. P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University and a Digital Fellow at MIT Sloan’s Initiative on the Digital Economy. Constantine Yannelisk is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Eric Zwick is an associate professor of finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

ProMarket is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.