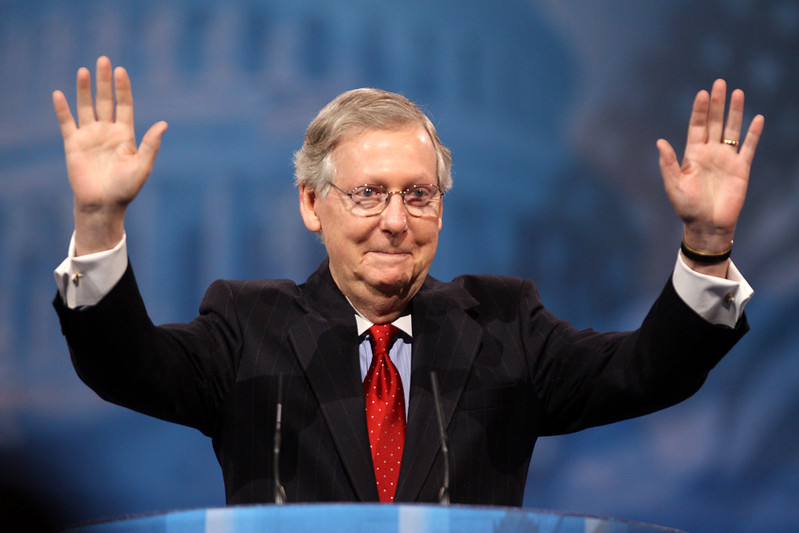

States are facing massive shortfalls due to the coronavirus outbreak. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has suggested letting states file for bankruptcy. Puerto Rico offers some hints as to whether it is a good idea or not. What happens after defaults? How can states share default costs between creditors and citizens?

States are facing massive shortfalls due to the coronavirus outbreak. Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell has suggested letting states file for bankruptcy. In this episode, Kate and Luigi explain why the debate over McConnell’s proposal is far more complicated than most people think.

In this episode, Kate and Special are joined by a special guest: David Keel, the S. Samuel Arsht Professor of Corporate Law at the University of Pennsylvania Law School and a member of the Puerto Rico oversight board. He is also the author of True Paradox: How Christianity Makes Sense of Our Complex World.

Read about Mitch McConnel’s proposal to allow states to file for bankruptcy due to economic losses stemming from the coronavirus outbreak:

Are you curious about Kate’s research on bankruptcy? Read the preliminary version of her paper A Typology of U.S. Corporate Bankruptcy. Here is the abstract:

“This paper constructs an empirical typology of large Chapter 11 debtors based on their objectives and levels of preparation at filling. Approximately two-thirds of the firms in the sample set out to reorganize while the remaining third aim to sell substantially all of their assets, either as a going concern or in liquidation.

Nearly 60% of firms enter bankruptcy already having negotiated with creditors and other constituencies. Excluding cases that involve significant litigation, firms that intend on reorganizing but ultimately liquidate represent only 5% of the total sample. Today’s bankruptcy environment appears broadly consistent with one in which assets are liquid and verifiable, but also one in which firms are occasionally confronted by shocks and complexities that prevent out-of-court negotiations.”

Also, you can read the paper that Luigi mentions in the episode on the connection between Puerto Rico’s fiscal crisis and Detroit’s problems. The paper is co-authored by Robert S. Chirinko (Department of Finance; Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute), Ryan Chiu (University of Illinois at Chicago), and Shaina Henderson (University of Illinois at Chicago).

Here is the abstract:

“What went wrong? Why did seemingly rational bond investors continue to purchase Puerto Rican debt with only a modest risk premium, even though the macroeconomic fundamentals were dismal? Why did financial markets fail to exercise market discipline and restrict capital flows to Puerto Rico? Given gloomy macroeconomic fundamentals and relatively low risk premia, investors were either stunningly myopic/misinformed, or Puerto Rican debt was implicitly insured by the U.S. government. This paper examines the latter hypothesis, which we label the “Treasury Put.”

The expectation of a federal bailout was perfectly reasonable given past behavior by the federal government, starting with the prior bailout of the city of New York. Evaluating the Treasury Put hypothesis with a minimal set of assumptions is possible given three unique features – the dire fiscal and economic conditions in Puerto Rico, a fortunate characteristic of Puerto Rican bond issuance, and a ‘seismic shock.’

Regarding the second feature, Puerto Rico issued both uninsured and insured general obligation bonds on the same day and, in many cases, with the exact same maturity. The associated bond price data allow for an accurate computation of the risk premia on Puerto Rican bonds. The third feature is the non-bailout of the city of Detroit in 2013 that effectively extinguished the Treasury Put. Puerto Rican risk premia were stable before the Detroit bankruptcy and bracketed by the risk premia on Corporate Aaa and Baa bonds.

However, after the Detroit bankruptcy, risk premia rose dramatically, thus identifying a sizeable Treasury Put of at least 300 basis points and a significant misallocation of capital to Puerto Rico. In effect, the Treasury Put was a form of regulatory forbearance. Institutional reforms that would eliminate the Treasury Put are considered, but none are found satisfactory.”

ProMarket is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.