Private equity portfolio companies are heavily indebted, and they aren’t generating enough cash to service debts. The steady increase in asset values since 2009 has enabled funds to make tremendous gains because of the use of borrowed money. But now they are exposed to tremendous losses should there be any sort of disruption. Is this the final stage before a blow-up?

In 1993, economists George Akerloff and Paul Romer wrote a paper on the conjoined two crises of 1980s finance. The first was mass junk bond defaults late in the decade, and the second was the savings and loan crisis of deregulated banks going bankrupt en masse as they engaged in an orgy of self-dealing and speculation.

The paper was called Looting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit, and in it, they described how financiers can profit by destroying corporations, using a particular strategy. “Our description of a looting strategy,” they wrote, “amounts to a sophisticated version of having a limited liability corporation borrow money, pay it into the private account of the owner, and then default on its debt.”

What Akerloff and Romer were basically talking about was a legal version of the bust-out scene from Goodfellas. In that movie, mobsters took an ownership stake in a restaurant they often frequented, and then used the restaurant’s credit to buy liquor, which they would move out of the back and sell at half off.

When the restaurant’s credit was all used up, they burned the restaurant to the ground to collect the insurance money. It was an intentional bankruptcy, a theft from creditors by those who had control of the restaurant and did not care what happened to the asset in the end.

A bust-out requires the ability to borrow from someone so that you can steal from the people lending you money. This is also true for its white-collar cousin. So the trick, for both the mobsters and the white-collar looters described by Akerloff and Romer, is to find a way to borrow money.

I’m reminded of this paper, and the bust-out scene in Goodfellas, because I’ve been trying to understand what is happening with private equity as the coronavirus induces a massive, if short-lived, shock to our economy.

The reason I’m reminded of this paper is because private equity is a business created in part by junk bond takeover specialists in the 1980s, who were the topic of Akerloff’s and Romer’s paper. What’s interesting about junk bond specialists is that they had a more insidious plan than the mobsters in Goodfellas. Mobsters just stole from the bank, which did not know that the restaurant had become an object to be looted. But financiers of the 1980s actually captured control of the bank.

Akerloff and Romer showed that both savings and loan executives and junk bond kings were making loans they knew could not be paid back, because they were often self-dealing. They would lend to entities in which they had a stake. And since they were lending money that was not theirs, they did not care if the loan went sour, as long as some of it got transferred to their own pockets.

In other words, the best way to get a lender to lend you money is to put an agent in charge of the bank who doesn’t care if that money is paid back. Bill Black, a bank regulator in the 1980s, later wrote a book about this time with the memorable title: The Best Way to Rob a Bank is to Own One: How Corporate Executives and Politicians Looted the S&L Industry.

“What’s interesting about junk bond specialists is that they had a more insidious plan than the mobsters in Goodfellas. Mobsters just stole from the bank, which did not know that the restaurant had become an object to be looted. But financiers of the 1980s actually captured control of the bank.”

How did this, um, “business model,” emerge? As usual, it was a series of policy changes that unleashed self-dealing across the economy.

In the early 1980s, Ronald Reagan radically rolled back antitrust enforcement over mergers, which meant that it became much easier to take over corporations. Still, it was difficult to buy a company unless you could get a loan from a big bank, limiting the pool of takeover participants to fellow big corporations like Dupont and white-shoe Wall Street icons, like former Nixon Treasury Secretary William Simon.

In addition to weakening laws against corporate mergers, Reagan also eroded white-collar criminal enforcement and deregulated the savings and loan industry. These changes allowed Michael Milken, then an investment bank employee at a small firm called Drexel Burnham Lambert, to begin organizing a new means of financing for takeovers. In 1983, Milken began staking a different class of corporate raiders, men like T. Boone Pickens, Carl Icahn, Nelson Peltz, and Henry Kravitz, with giant pools of money he raised by selling “high-yield bonds,” more commonly known as junk bonds.

These new takeover artists used these pools of money to buy corporations that generated cash, had little debt, and owned assets. The theory, promoted by law and economics scholars Milton Friedman, Henry Manne, and Michael Jensen, was that the market for corporate control moved assets from bad managers to good ones. And while a raider might buy a company and improve corporate operations, more often he would sell assets, fire employees, give the cash to himself through various mechanisms, and borrow money against the corporation he had just purchased. Sometimes raiders would have the corporations they just acquired shift working capital or corporate pension money into junk bonds to finance more takeovers, in a daisy chain.

High yielding bonds could seem like a good deal for a really long time, even as the underlying financial assets against which the bonds were lent deteriorated in quality. Drexel bonds in particular seemed too good to be true. They had an attractive interest rate and never defaulted. As bank regulator William Seidman put it:

“As far as we could determine, [Milken]’s underwritings never failed and appeared to be marketed successfully, no matter how suspect the company or how risky the buyout deal that was being financed. Other investment houses had some failed junk bond offerings, but Drexel’s record was near perfect.

We directed our faculty to research the matter.. . . The faculty came up with no plausible explanation; like so many others they fell back on the thesis of the junk bond king’s unique genius.”

The reason was likely not genius, but market manipulation.

Many Drexel bonds eventually went sour, because the basic idea behind any bust-out is to screw the creditor. Akerloff and Romer realized that the people who owned junk bonds would not notice problems, because they largely entrusted their money to pension and mutual fund managers and insurance company executives. These agents, who controlled pools of other people’s money, had different incentives than the actual people whose money they were entrusted with.

There were a number of mechanisms Milken used to keep the confidence of bond-holders. The agents for the investors could be in on Milken’s game. He could favor trade, offering to let certain fund managers into private deals for themselves personally if they used the money they controlled to buy bonds Milken wanted to offload. Junk bond investors would often have corporations work with bondholders to restructure or roll-over bonds, rather than missing coupon payments, so as to make it appear that junk bond default rates were lower than they really were.

And then finally, if necessary Milken could simply put losses into government-backed vehicles, savings and loan banks, who used accounting rules to avoid losses, and then eventually were taken over by the taxpayer.

Charles Keating, a major S&L villain who ran the infamous Lincoln Savings and Loan, was a Milken ally and a buyer of junk bonds. As Akerloff and Romer put it, “The junk bond market of the 1980s was not a thick, anonymous auction market characterized by full revelation of information. To a very great extent, the market owed its existence to a single individual, Michael Milken, who acted, literally, as the auctioneer.”

Was this legal? Some parts were. And the other parts? “For half a million dollars you could buy any legal opinion you wanted from any law firm in New York,” said one banker anonymously. Moreover, because of savings and loan laws passed in 1980 and 1982, S&Ls, formerly sleepy banks that only lent to people buying homes, could now buy junk bonds using depositor’s money, what a banker called “the key to the US Treasury.” As Ben Stein put it, “the federal government basically repealed Glass-Steagall if an investment bank just called its commercial banking captive a ‘savings and loan.’”

This game could not go on forever, but it could go on for a very long time, as long as Milken had a way to hide a small percentage of his losses. From the mid-1970s to 1989, the junk bond seemed to flourish. And as takeover artists bid up corporate asset prices with borrowed money, the price of stocks would keep going up, which seemed to justify bond values.

After all, if a corporation could always be sold at a high price to service a large debt load. But then, when Milken went to jail, the whole scheme unraveled. According to Stein, Milken’s bank issued around $220 billion in junk bonds, with a loss to investors and taxpayers of something on the order of $40 billion and $100 billion. But these losses understate the impact; by making it cheaper to borrow for takeovers, the junk bond kings influenced $1.3 trillions of dollars of assets that changed hands in the decade.

These kinds of transactions were highly consequential in the American economy. In the 1980s, the American corporation, which had traditionally kept a thick layer of cash and done a substantial amount of R&D, became far more debt-laden and responsible to short-term financial incentives to deliver cash to shareholders, lest a corporate raider see a target.

“The hostile tender offer,” said management consulting legend Peter Drucker, “has become a dominant force—many would say the dominant force—in the behavior and actions of American management, and almost certainly a major factor in the erosion of American technological leadership.”

The Bailouts Begin

But did Milken’s jail sentence end the game? No. The first giant bailout in the early 1990s during the Savings and Loan crisis was in many ways a bailout of the junk bond kings. And then Bill Clinton, coming to power in 1993 largely as a result of the economic downturn (partly) from the debt-overhang, brought in a Wall Street-friendly cabinet.

Democrats had traditionally been an anti-Wall Street party. But Clinton’s Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, who had been involved at Goldman Sachs in the mergers and acquisitions junk bond world dominated by Milken, bailed out large US banks that had lent too much to Mexico.

Chris Arnade, a trader at the time, described the shift that the Democratic embrace of Wall Street enabled.

“The use of bailouts should have also been a reason to heavily regulate Wall Street, to prevent behavior that would require a bailout. But the administration didn’t do that; instead they went the opposite direction and continued to deregulate it, culminating in the repeal of Glass Steagall in 1999.

It changed the trading floor, which started to fill with Democrats. On my trading floor, Robert Rubin, who had joined my firm after leaving the administration, held traders attention by telling long stories and jokes about Bill Clinton to wide-eyed traders.

Wall Street now had both political parties working for them, and really nobody holding them accountable. Now, no trade was too aggressive, no risk too crazy, no behavior to unethical and no loss too painful. It unleashed a boom that produced plenty of smaller crisis (Russia, Dotcom), before culminating in the housing and financial crisis of 2008.”

The Clinton bailouts of the 1990s had their mirror image in the Bush/Obama bailouts of 2008-2010. And in both the downturn of 2000 and 2008, high-yield riskier corporate bond debt deteriorated more than expected, meaning that the game Milken invented never really went away. Higher than expected default rates mean that credit quality is being hidden by middlemen in the market, and poor credit quality comes out in a downturn.

Politically, private equity continued to gain power, using the same political patrons. During the Great Recession, as he had with Clinton, Rubin served as an advisor to Barack Obama, who bailed out Wall Street again, through both a direct bailout fund administered by the Treasury and through lending by the Federal Reserve.

Then, a few weeks ago, credit spreads for junk bonds blew out, until Congress passed a massive bailout bill and the Fed stepped in. As taxpayers had in the early 1990s, and as they had in 2008, taxpayers ensured that owners of financial assets would not have to take the downside for the risks they had incurred. And who structured the Coronavirus package to move $4 trillion to Wall Street? Powerful House Democratic Ways and Means leader Richard Neal, who recently described how he and Pelosi put together the bailout, told a reporter that upon learning about the need for a bailout, he “immediately sought out advice from Bob Rubin.”

So that’s three economy-shaking bailouts: one in the 1990s, one in 2008, and one in 2020. The policy response to financial policy isn’t just the same, it’s literally the same people doing the same things. (I’m leaving out a few other bailouts, but the point stands).

“A Better Form of Capitalism”

Today, the business Michel Milken invented has been rebranded as private equity. Milken’s alums are all over the industry. Leon Black and Josh Harris were at PE giant Apollo (where Milken’s son worked until recently), Stephen Feinberg runs Cerberus, Bennett Goodman is at Blackstone, Ken Moelis runs a boutique investment bank currently advising the Trump Treasury Department on the bailouts, and so on and so forth on. Others were in and around that world; Fed Chair Jerome Powell, for instance, did M&A in the 1980s and then was at PE giant the Carlyle Group in the 1990s.

The profit model of today’s private equity is the “2 and 20” compensation system. Most of private equity general partners take an annual management fee, between 1-2 percent of the total amount committed by investors, and then they take an additional 20 percent of the upside (usually in excess of a benchmark rate). That can be a massive payout, which is the upside on capital gains and dividends.

Private equity firms take their investors’ money and use it, along with issuing junk bonds, buy companies, which they run like different unrelated divisions of a conglomerate. This portfolio is like having a bunch of stocks, except these are private companies, which they buy and sell. PE firms also buy real estate and can buy any financial asset, like paper mills or tax credits. But if their portfolio companies go bankrupt and they lose their equity, then they get neither upside nor management fees.

PE firms use the same rationale as raiders did in the 1980s. They market themselves as helping to restructure companies to make them better run, getting the company away from the public markets where investor scrutiny prohibits executives from focusing on long-term value creation. It is a far more refined public relations operation, less openly piggish than the 1980s “greed is good” model.

There’s quasi-utopian rhetoric and Ivy encrusted elitism involved; Yale endowment chief David Swensen, a key validator for private equity investors, calls this model a “superior form of capitalism.”

Of course, the “better form of capitalism” utopian rhetoric is nonsense. Really, PE firms just buy corporations by using debt, as Milken did in the 1980s; the average buyout is 65 percent debt-financed. And despite the fact that there are many different PE firms, the industry is opaque and tight-knit. In 2006, investors sued 13 of the largest PE funds in the business for big-rigging, alleging these firms worked together in “clubs” and agreed to collectively hold down the price of firms they were bidding on.

Allegations of collusion shouldn’t be a surprise. After all, PE execs learned the business from Michael Milken, and Milken is nothing if not a fount of circumstantial evidence of unethical behavior. (My favorite is this 2017 story in the Wall Street Journal on the suspicious timing of charitable donations of stock).

The business model of the 1980s has been institutionalized in ways that are hard to conceptualize. Sycamore Partners’ takeover of Staples was a recent legendary leveraged buy-out that shows how PE really works. Sycamore Partners is a private equity firm that specializes in buying retailers. Sycamore bought Staples for roughly $1.6 billion in 2017, immediately had Staples take out $5.4 billion of loans, acquired another company, and then paid itself a $300 million payment and then a $1 billion special dividend.

Then, Sycamore had Staples gift its $150 million headquarters in the suburbs of Boston for free, after which Staples signed a $135 million ten year lease with Sycamore to lease back its own building. I’ve asked Sycamore questions about its rent deferral, but their PR specialist, former New York Times editorial staff member Michael Freitag, told me that “Sycamore does not comment on these matters.”

It’s not the only time the fund has done this.

The Wall Street Journal reported several instances in which Sycamore would buy a corporation, load it with debt, and then “sell-off” the valuable pieces of that corporation to Sycamore. Or it would find other ways of transferring money to itself, by forcing losing portfolio companies to do business with other Sycamore companies at preferential rates.

Basically, what’s happening is the laundering of assets and debts. This is a common tactic in the industry, one exposed when Apollo and TPG bought giant casino Caesars Entertainment right as the financial crisis of 2008 unfolded and then tried to stiff creditors. The end result would be a bankrupt worthless corporation, losing bondholders, and the PE fund not having to take losses. It’s the Akerloff/Romer paper, or a billion dollar bust-out.

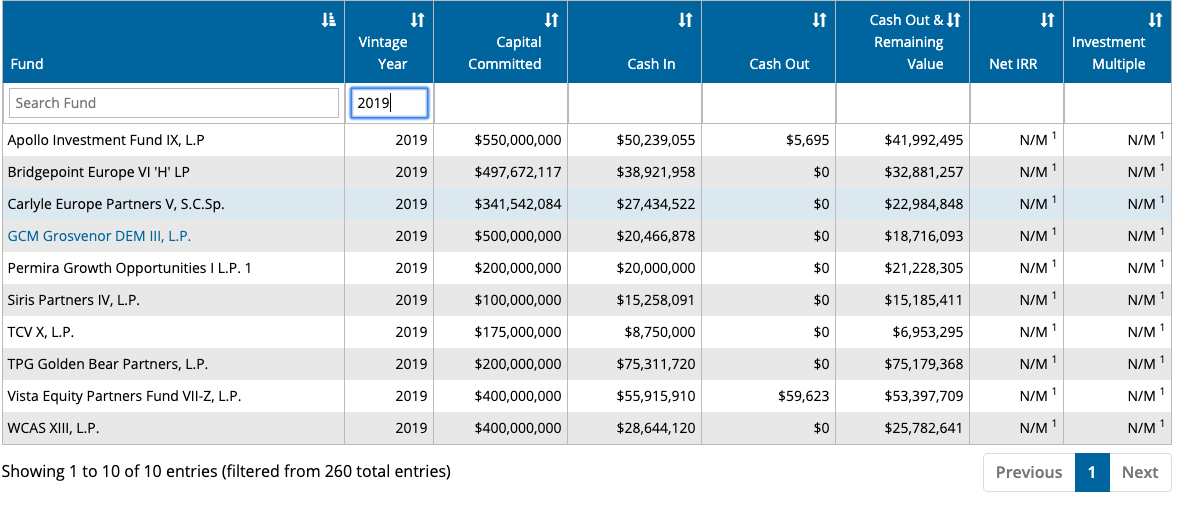

This kind of activity hasn’t caused any pause in the growth of the industry. Today, private equity has roughly $6 trillion in “assets under management,” mostly from pension funds and wealthy people. The chief investment officer of Calpers, the largest public pension fund, once said, “We need private equity, we need more of it, and we need it now.” Here’s how much Calpers put into private equity in 2019:

The Corovirus Crisis

All of this brings me to the current crisis in the industry. Last week, I went into why doctor staffing companies, owned by Blackstone and KKR, are cutting pay in a pandemic. But there’s more pain that private equity is dishing out: Axios reported that Staples, the private equity-owned office retailing chain, is stiffing landlords and refusing to pay rent on its stores, as is private equity-owned Petco (by CVC Capital Partners). Meanwhile, a different private equity-owned pet chain, Petsmart, is refusing to close its dog grooming salons and giving talking points to its employees misconstruing the law.

What’s interesting here is not just the use of power to extract concessions, but something else: Desperation. Petsmart is basically telling its employees to mislead law enforcement, and Staples is stiffing landlords (though one wonders if Staples is still paying rent to Sycamore for its headquarters). This isn’t normal. Indeed, something is wrong in private equity land. One of the biggest, and oldest, private equity firms, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, or KKR, with hundreds of billions of dollars under management, just warned investors that its business is in trouble.

Part of the risk here is what every company is experiencing, which is a depression. KKR told investors that its asset values “are generally correlated to the performance of the relevant equity and debt markets.” Some portfolio companies, the Wall Street Journal reported, “in sectors such as health care, travel, entertainment, senior living and retail could become insolvent if the disruptions from the pandemic and measures taken to stem them such as business shutdowns it aren’t ended.”

This is obviously true throughout the space, with a host of private equity companies whose investments have obviously evaporated. Vista Equity Partners paid $1.9 billion for yoga studio software company MindBody, and Bain Capital bought cheerleading monopoly Varsity in 2018 for $2.5 billion. Both companies are engaged in layoffs, and are in trouble.

And this gets to the much more serious problem that PE is having with this coronavirus crisis, which is potential trouble with the engine that makes the whole thing run, or borrowers. As KKR put it to investors recently, “We and our funds may experience similar difficulties, and certain funds have been subject to margin calls when the value of securities that collateralize their margin loan decreased substantially.”

Many of their portfolio companies were leveraged up with debt to increase returns, but the downside of leverage is that it magnifies losses. Envision, the KKR-owned doctor staffing firm, just hired an investment bank to find a way to renegotiate its massive $7.5 billion debt load; portions of its loans are trading are trading at 60 cents on the dollar. A company that can’t pay back its loans is bankrupt. And while Staples hasn’t defaulted on its debt, it is defaulting to creditors when it stopped paying rent. (I asked Sycamore if they have revalued Staples, but I didn’t get an answer.)

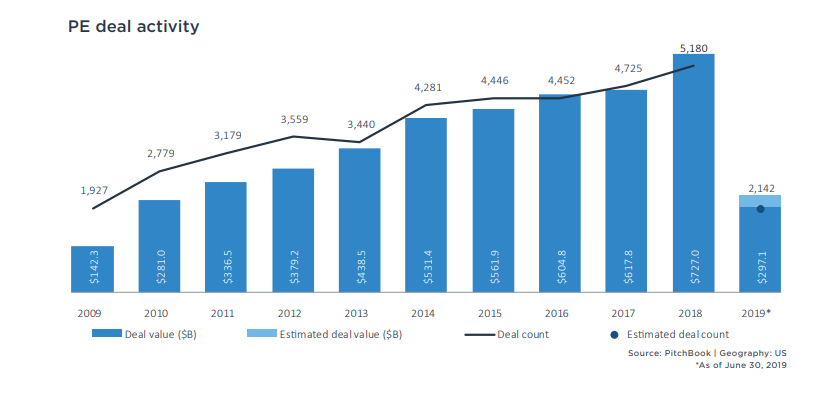

Between the 2008 financial crisis and the pandemic, it had been smooth sailing for private equity firms, who had in turn gotten more and more aggressive.

Pension fund investors have thrown more money at PE firms, and debt investors, hungry for anything with a return, have also gotten more hungry for higher yields. PE firms have even launched their own debt funds, meaning that they are both borrowing money to buy firms and lending money to support takeovers. Basically, there’s now an entire shadow banking system of private equity giants and their various captive institutions lending and borrowing from each other, and buying and selling each others’ companies.

“Private equity is undergoing what the great theorist Hyman Minsky pointed out is the Ponzi stage of the credit cycle in capitalist financial systems. This is the final stage before a blow-up.”

As they passed firms to one another, took them public and brought them private, loaded them up with debt and then more debt, it meant that the price of firms had been steadily going up. As a result, as Daniel Rasmussen and Greg Obenshain reported in their excellent article published just before the crisis in Institutional Investor magazine, PE funds are paying higher prices for firms with less cash flow, even as loan quality has deteriorated.

Private equity is undergoing what the great theorist Hyman Minsky pointed out is the Ponzi stage of the credit cycle in capitalist financial systems. This is the final stage before a blow-up. As Minsky observed, a period of placidity starts with firms borrowing money but being able to cover their borrowing with cash flow. Eventually, there’s more risk-taking until there’s a speculative frenzy, and firms can’t cover their debts with cash flow. They keep rolling over loans and just hope that their assets keep going up in value so that they can sell assets to cover loans if necessary. To give an analogy, in 2006, when people in Las Vegas were flipping homes with no income, assuming that home values always went up, that was the Ponzi stage.

Now, what happens with Ponzi financing is that at some point, nicknamed a “Minsky Moment,” the bubble pops, and there’s mass distress as asset values fall and credit is withdrawn.

Selling assets isn’t enough to pay back loans, because asset prices have collapsed and there’s not enough cash flow to service the debt. Mass bankruptcies or bailouts, which are really both a restructuring of capital structures, are the result.

I think you can see where I’m going with this.

PE portfolio companies are heavily indebted, and they aren’t generating enough cash to service debts. The steady increase in asset values since 2009 has enabled funds to make tremendous gains because of the use of borrowed money. But now they are exposed to tremendous losses should there be any sort of disruption. And oh, has this ever been a disruption. The coronavirus has exposed the entire sector.

Organizing a Bailout

There are now three possible paths to deal with this Minsky Moment.

First, policymakers can force PE firms to recognize losses and put their portfolio companies through a series of corporate bankruptcies, which would essentially declare a huge portion of private equity funds as losers. Going down this path would be honest and would set up the economy to grow again, but it would hit these guys in two ways, since many PE firms both own portfolio companies that would go bankrupt, and operate debt funds who would lose.

This path would wipe out trillions of dollars off pension funds, and turn a lot of PE billionaires into mere millionaires. It is a reasonable path for most of us, because while mass bankruptcies can lead to even more job losses, the government can offset such job losses with spending programs to set up a more resilient society. But it’s very unreasonable for the PE execs at the top of the pecking order.

Second, policymakers can find a way to reflate the bubble and keep the debt roll-over continuing. Such a reflation strategy requires temporary government aid to prevent debt defaults. But while you can restructure debts and change capital structures, you can’t force customers back to using yoga studios or getting their dogs groomed during a pandemic. This pressure is why so many PE execs are eagerly pestering Trump to get the economy reopened, they are extremely wealthy men who are also very heavily indebted, and their debt burdens are weighing on them.

Third, find a sucker to take the losses. This is the bailout for which private equity has been lobbying furiously. NBC News reported that Apollo executives sent an email to Jared Kushner asking for a bailout (“There has been no MORAL HAZARD. We have a totally unique situation”).

Can a Bailout Work?

The CARES Act, which is the bailout, passed. And Apollo is now telling investors it has identified 250 ways it can profit. The main bailout is through the Federal Reserve, which is buying junk bonds and commercial mortgage bonds. Last week, according to the FT, the Fed’s announcement it would be buying these debt instruments “sparked the biggest rally in junk bonds in more than a decade.”

The Fed isn’t even buying individual junk bonds, it’s buying bundles of junk bonds held by exchange-traded funds, meaning that a private agent like Blackrock will be standing in for the Fed. The Fed, in other words, may not even be in charge of the renegotiations for the bonds it will own should there be defaults.

So has it worked? On first glance, yes. Even the prospect of the Fed buying junk bonds has restored the market for high yield bonds.

“The average yield on high-yield bonds had fallen from a high of 11.4 per cent on March 23 to 8.2 per cent on Monday. Yields go down when bond prices go up. Loan prices had risen from an average of 76 cents on the dollar to more than 86 cents over the same period, according to an index run by the Loan Syndications and Trading Association.”

Lenders are willing to lend risky companies; recent issuers of junk bonds include movie chain Cinemark, retailer Burlington, travel company Sabre, aerospace supplier TransDigm and energy company Ferrellgas. And New Street Research, a telecommunications and technology analysis firm, just upgraded their assumptions for two highly leveraged companies, Charter and Altice, which are issuing more debt and buying back shares. While not private equity-owned firms, these companies do correlate with PE portfolio companies, since they are heavily indebted and play some of the same financial games as PE.

So the Fed bailout is already moving the bond market to enable share buybacks, which is exactly what Elizabeth Warren, who voted for the bailout, said she didn’t want.

And yet, despite the desire of Congress, the Fed, and President Trump to prevent a collapse of private equity, it’s hard to see a bailout really keeping the credit cycle going. As Rana Foroohar observes, we have both a corporate debt crisis where companies just can’t pay back what they owe, and a real estate crisis because real estate values are simply too high, having doubled since 2008. PE owns corporate equity, corporate debt, and real estate.

The coronavirus is going to make these dynamics even worse. The massive job losses are going to mean that people simply can’t afford rent, and young people won’t be able to borrow to buy homes.

The pandemic could change business in more fundamental ways, with more people telecommuting and less travel, leading to a reduced need for commercial real estate and convention space. And the destruction of a large number of small businesses, and the monopolization of commerce in the hands of Amazon and Walmart and a few others, if that is allowed to happen, will mean further erosion of rental income streams.

Basically, there is massive deflation, and that’s not going to change just because lockdowns begin easing. Tens of millions of people no longer have income, and even those who do are afraid to go back to their old lifestyles. The Fed ultimately can’t print a functional economy. And at the end of the day, no matter how many games you play with debt loads and capital structures, firms have to have customers, and people can only be customers if they have income.

All of which brings me back to the paper Akerloff and Romer wrote in 1993 about the business model of a certain kind of financial firm, one that looks a lot like how a large part of the private equity industry operates.

These two economists pointed out that these kinds of schemes, though they can last for a long time, can’t go on forever. The only question is how much damage they do. Or to put it differently, in Goodfellas, though the bust-out was profitable, in the end, the restaurant burned down.

Matt Stoller is the author of Goliath: The Hundred Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy and Director of Research at the newly-founded American Economic Liberties Project. This column originally appeared in BIG, Stoller’s newsletter on the politics of monopoly. You can subscribe here.

ProMarket is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy