In March 2018, Tesla’s Board of Directors granted Musk a potential bonus of 20,264,042 stock option awards under a plan that uses “adjusted EBITDA” as one of its metrics. According to general accounting principles, Tesla recorded a 2019 net loss of $862 million, but thanks to using different accounting principles this loss became an adjusted EBITDA profit of $2.985 billion.

On Thursday, March 12, Los Angeles Times reporter Russ Mitchell filed a story about Tesla and its CEO Elon Musk’s reaction to the coronavirus crisis because Tesla has significant operations dependent on China:

“So far, Musk has tweeted nothing about the current state of Tesla’s new Shanghai factory, nor has he publicly issued other corporate information related to the coronavirus.

He’s said nothing about the current level of production in Shanghai, which reopened on Feb. 10 after a 10-day government-ordered shutdown. Nor about the company’s sales prospects in China, where the overall auto industry suffered an 80% decline in sales in February. Also, no talk about supply chain issues.

He did, however, tweet this on March 6: ‘The coronavirus panic is dumb.’

The company’s stock price has dived with the rest of the market, plummeting 39% from a closing high of $917.42 on Feb. 19 to $560.55 as of Thursday’s close.”

The LA Times’ Mitchell also waded into the status of Musk’s bonus writing: “if the stock price holds roughly above $542 a share for over the next few weeks, Musk stands to reap a huge bonus.”

In March 2018, Tesla’s Board of Directors granted Musk a potential bonus of 20,264,042 stock option awards under a CEO Performance Award plan that uses “adjusted EBITDA” as one of its metrics.

Adjusted EBITDA for Tesla is defined under its award plan as “net income (loss) attributable to common stockholders before interest expense, provision (benefit) for income taxes, depreciation and amortization, and stock-based compensation.”

Musk will get about $1 billion in stock options if certain revenue and market capitalization targets, in addition to the adjusted EBITDA target, are met. For the first award, the company’s market value must average $100 billion or more over both a six-month and 30-day period. (Its market cap exceeds that threshold at current prices.)

The coronavirus panic is dumb

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 6, 2020

Mitchell writes:

“Tesla has lost money every year since it went public in 2010. For example, the automaker lost $775 million in 2019 under generally accepted accounting principles, or GAAP, the key profit measure authorized by the Financial Accounting Standards Board.”

Tesla turned chronic losses into profits under its non-GAAP metric magic, creating adjusted EBITDA profit in 2019 of $2.985 billion versus a net loss (according to GAAP) of $862 million, according to its annual report.

The market capitalization target for the CEO bonus payouts after the first payout increase by increments of $50 billion, starting with the initial $100 billion requirement.

As of December 31, 2019, Tesla says in its annual report, two operational milestones required to get the first payout under the plan have been achieved: (i) $20.0 billion total annualized revenue and (ii) $1.5 billion annualized adjusted EBITDA, each subject to the formal certification by our Board of Directors, while the market capitalization milestones had not yet been achieved. Consequently, no shares subject to the 2018 CEO Performance Award had vested as of the date of the annual report filing.

And as of December 31, 2019, the operational milestones required to get the second payout under the plan were considered probable of achievement:

- Adjusted EBITDA of $3.0 billion

- Total revenue of $35.0 billion

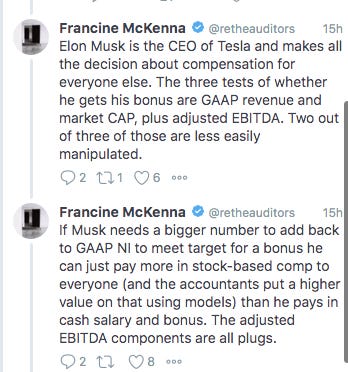

I commented in the LA Times article:

“Using EBITDA to determine executive pay ‘allows a company to make adjustments to their GAAP income using their own judgment and discretion,’ said Francine McKenna, who runs the accounting and auditing online newsletter, The Dig. Tesla is hardly the only company to use this method to determine compensation, she said, but Tesla is especially aggressive.”

I explained later on Twitter why using “adjusted EBITDA” to determine bonus eligibility is so self-serving. That’s because, in addition to adjusting GAAP earnings to add back expenses for interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, the double non-GAAP crap adjustment at Tesla also adds back stock-based compensation expense.

Tesla’s annual report makes it very clear they will plug the numbers if it looks like Musk might make it.

“If such operational milestone becomes probable any time after the grant date, we will recognize a cumulative catch-up expense from the grant date to that point in time. If the related market capitalization milestone is achieved earlier than its expected achievement period and the achievement of the related operational milestone, then the stock-based compensation expense will be recognized over the expected achievement period for the operational milestone, which may accelerate the rate at which such expense is recognized.“

Models, which use lots of estimates that are subject to management’s judgment and discretion, are used to determine other components of the 2018 CEO Plan.

“The market capitalization milestone period and the valuation of each tranche are determined using a Monte Carlo simulation and is used as the basis for determining the expected achievement period.

The probability of meeting an operational milestone is based on a subjective assessment of our future financial projections.”

Of course, Tesla is not the only company that uses subjective, subject-to-management-discretion-and-judgment metrics such as “Adjusted EBITDA,” and models based on simulations to determine pay for its executives.

“Companies like Broadcom Ltd. and Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings Ltd. are adding back millions in ‘ghost revenue’—deferred revenue that accounting standards force them to write off after an acquisition—when calculating executive bonuses, an issue that is taking on new resonance after a former Symantec Corp. employee complained about the practice internally and prompted an audit committee investigation.”

In 2019, Norwegian Cruise Lines no longer adjusts its revenue for the acquisition-related “ghost” deferred revenue, but its annual report says it still uses a lot of non-GAAP metrics for reporting and executive compensation purposes:

“This annual report includes certain non-GAAP financial measures, such as Net Revenue, Net Yield, Net Cruise Cost, Adjusted Net Cruise Cost Excluding Fuel, Adjusted EBITDA, Adjusted Net Income and Adjusted EPS.

We believe that Adjusted EBITDA is appropriate as a supplemental financial measure as it is used by management to assess operating performance.

We also believe that Adjusted EBITDA is a useful measure in determining our performance as it reflects certain operating drivers of our business, such as sales growth, operating costs, marketing, general and administrative expense and other operating income and expense.

In addition, Adjusted Net Income and Adjusted EPS are non-GAAP financial measures that exclude certain amounts and are used to supplement GAAP net income and EPS. We use Adjusted Net Income and Adjusted EPS as key performance measures of our earnings performance.”

Norwegian Cruise Lines uses Adjusted EPS to determine executive cash bonus awards and Adjusted EPS and Adjusted ROIC to determine executive equity awards.

“Adjusted EPS. Net income, adjusted for supplemental adjustments, divided by the number of diluted weighted-average shares outstanding.

Adjusted EBITDA. Earnings before interest, taxes, and depreciation and amortization, adjusted for other income (expense), net and other supplemental adjustments.

Adjusted ROIC. Adjusted EBITDA less depreciation and amortization, adjusted to exclude amortization of intangible assets related to the Acquisition of Prestige, divided by debt and shareholders’ equity, averaged for four quarters.”

What kinds of unusual items are adjusted out of earnings to arrive at Adjusted EBITDA, Adjusted Net Income, Adjusted ROIC, and Adjusted EPS? It is entirely up to management, subjective and varies from period to period.

“The amounts excluded in the presentation of these non-GAAP financial measures may vary from period to period; accordingly, our presentation of Adjusted Net Income and Adjusted EPS may not be indicative of future adjustments or results.

For example, for the year ended December 31, 2018, we incurred Secondary Equity Offering expenses of $0.9 million. Similar expenses were not incurred in the year ended December 31, 2019.

We included this as an adjustment in the reconciliation of Adjusted Net Income since these expenses were not representative of our day-to-day operations and we have included similar nonrepresentative adjustments in prior periods.“

Watch to see if Norwegian Cruise Lines executives get their bonuses, regardless of the performance of the company during this Coronavirus crisis, based on other supplemental adjustments for the “expenses that were not representative of our day-to-day operations,” associated with the impact of the crisis.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article appeared in The Dig, Francine McKenna’s newsletter. You can subscribe here. Francine McKenna is an independent journalist whose newsletter, The Dig, covers accounting, audit, and corporate governance issues at public and pre-IPO companies.

The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.