The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority recently criticized Google and Facebook’s excessive market power. American regulators, on the other hand, have allowed them to consolidate their influence with almost no restrictions, and the Justice Department’s chief antitrust enforcement official has recused himself from the Google investigation because he used to be a Google lobbyist.

Editor’s note: This is the sixth and final post in a series on the status of competition in search, social media, and digital advertising markets. It explores the main preliminary findings of a large market study conducted by the CMA, as well as a December 2019 antitrust condemnation of Google in France for abusing its dominant position in the French market for digital ads. The rest of the series can be found here.

Previous posts explored the preliminary findings of a large market study conducted by the British Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) on the status of competition in British digital advertising markets. In sum, the CMA’s conclusions were that Google and Facebook have grown so “large and have such extensive access to data that potential rivals can no longer compete on equal terms.”

This begets some questions on the current status of competition in the companies’ main turf, the US. There is little reason to believe that US markets differ much from those analyzed by the CMA. Indeed, the Stigler Report, which focused on the US, raised many important concerns regarding the market power of digital platforms such as Google or Facebook.

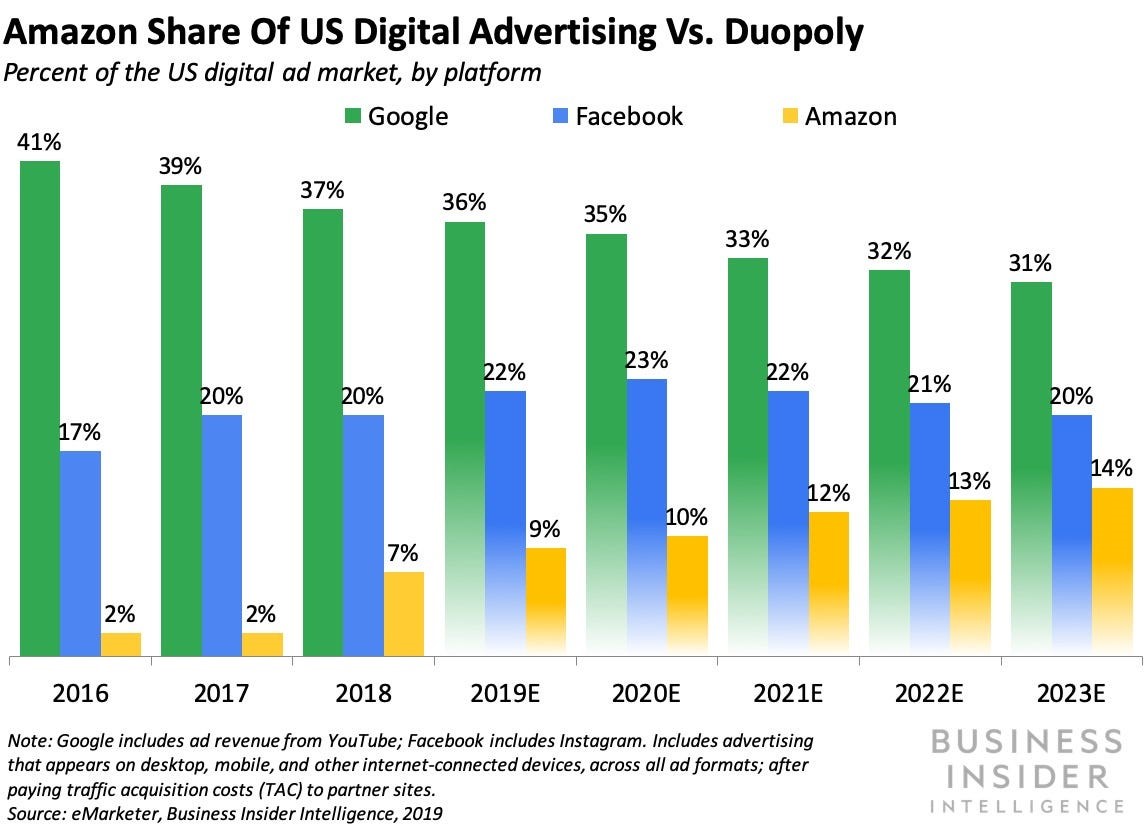

Both companies control much of the US digital ecosystem—reports indicate, for example, that together Google and Facebook account for 60 percent of all US online ad spending, a percentage higher than their estimated combined share of 54 percent in the UK.

Data from StatCounter, a web analytics firm, indicates that Google controls 88.65 percent of the US search market, just slightly below its 90 percent share in the UK. I am unaware of detailed US public data separating social media companies according to “time spent in the platform,” the best metric to measure social media engagement and the one used in the UK to calculate Facebook’s share. Some imperfect estimates point to a Facebook share of “time spent” at around 70 percent in 2019.

The same StatCounter data referenced above indicates that Facebook/Instagram only control 45 percent of the UK social media market, versus 59 percent in the US. If the time spent on the platforms tracks the StatCounter data, Facebook’s US market share would be significantly above the 75 percent found in the UK, an increase that justifies the 6 percent increase in the total online advertising revenue of Facebook and Google mentioned above.

Google and Facebook also adopt the same market strategies in the US as in the EU or the UK. The CMA expressed potential concerns about practices that also took place in the US, such as those around Google’s leveraging of its control over search markets to expand in other markets, payments to Apple to be the default search engine on iPhones/Safari, and Google’s vertical integration and opacity leading to potential abuses in open display markets.

The CMA‘s concerns about Facebook’s opacity and its deprecation of competitors’ access to its platforms also find an echo in this side of the Atlantic. Facebook blocked Twitter’s access to some of Facebook’s functionalities when it launched Vine, a short video app that competed with Facebook.

The CMA’s description of an interoperable social media could as well be Power Ventures, a company whose goal was to become a meta-social media but that went out of business after Facebook used a federal anti-hacking criminal law to restrict its access to Facebook servers. Snapchat’s Project Voldemort files detailed many of the “aggressive” tactics Facebook has adopted to prevent the company from growing. Whilst there are important differences between antitrust regimes in the EU and the US, such attempts by a dominant company to block the expansion of competitors deserve close scrutiny anywhere.

Indeed, Google started consolidating the US online advertising markets in 2007 when it acquired what was back then (and still is) the leading online ad exchange, DoubleClick. In December of that year, the FTC cleared the transaction with a prediction and a promise. The prediction was:

“Because the evidence failed to show that DoubleClick has market power in the third party ad serving markets, it is unlikely that Google could effectively foreclose competition in the related ad intermediation market following the acquisition.

The evidence also showed that it was unlikely that Google could manipulate DoubleClick’s third-party ad serving products in a way that would competitively disadvantage Google’s competitors in the ad intermediation market. Further, the evidence demonstrated that any aggregation of consumer and competitive data resulting from the acquisition is unlikely to harm competition in the ad intermediation market.

These factors resolved any competitive concerns related to these markets.”

The promise was:

“Because the evidence did not support the theories of potential competitive harm, there was no basis on which to seek to impose conditions on this merger.

We want to be clear, however, that we will closely watch these markets and, should Google engage in unlawful tying or other anticompetitive conduct, the Commission intends to act quickly.”

12 years later, it looks increasingly clear that the prediction was wrong and that the promised enforcement never came. Google would go on to acquire, unchallenged, more than 150 companies during the period, including four important acquisitions in online advertising—AdMob in 2009, Invite Media in 2010, AdMeld in 2011, and Adometry in 2014—, that cost the company more than $1.3 billion.

We do not have a public, official analysis of the status of competition in US online ad markets. The FTC and the Department of Justice are lagging behind their peers in investigations and in disclosure. While many authorities around the world have opened and closed many investigations on potential antitrust abuses in digital markets, we only know more about one past investigation into Google because of a faulty partial disclosure of an internal FTC memo to the Wall Street Journal.

In this case, the FTC investigated a range of potentially anticompetitive conduct by Google, including questions about search bias and self-preferencing, scraping of rivals’ data by Google, Google’s restriction on multi-homing by advertisers, and exclusive deals that prevented the development of rival search engines.

After a long investigation, the FTC’s technical staff concluded that Google’s “conduct has resulted—and will result—in real harm to consumers and to innovation in the online search and advertising markets”. By some FTC estimates, Google’s search syndication agreements and AdWords limitations foreclose up to 66 percent of the relevant market.

FTC Commissioners disagreed (we do not know their reasons) and the agency ended up settling the case in January 2013, requiring only minor changes to Google’s practices. Estimates from the time indicate that Google already controlled many online advertising markets and accounted for 31 percent of total online ad spending in the US, being almost eight times larger than the second-place Facebook.

Seven years later, the DoJ is now promising to be “well into the fairway” of gathering data and evidence on tech giants’ behavior. It is not very encouraging, though, that the head of the DoJ was a lobbyist for Google during the approval of the DoubleClick acquisition, forcing him to recuse himself from the investigation. While we wait for the DoJ, the “good” news on the competition front is that Amazon is leveraging its e-commerce market clout to grow in online ads, challenging some of Google’s dominance in search advertising.

However, both the CMA and the AdC concluded that Amazon is an imperfect competitor, at best. Amazon is only focused on retail search, a limited share of Google’s search revenue. Unless Amazon greatly expands away from retail, a likely scenario is that online advertising markets end up as two monopolies (general search and open display) and two duopolies (display and retail search).

Together, the Google-Facebook-Amazon trio will control an even larger share of the online ad market than they do now. As online ads are bound to grow at the expense of legacy media, the money that has been previously dispersed amongst thousands of newspapers, local and national TV channels, and radio networks with different points of view will go to companies whose control rests solely in the hands of four white men: Mark Zuckerberg, Larry Page, Sergey Brin and Jeff Bezos.

Filippo Maria Lancieri is a fellow at the Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State. He is also a JSD Candidate at The University of Chicago Law School.

The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.