The global economy and financial markets are seriously hit by the coronavirus outbreak. Central banks can do something, but monetary policy is not enough. A fiscal stimulus might mitigate the impact, but the record-level outstanding amount of public and private debt adds additional risk to the current perfect storm.

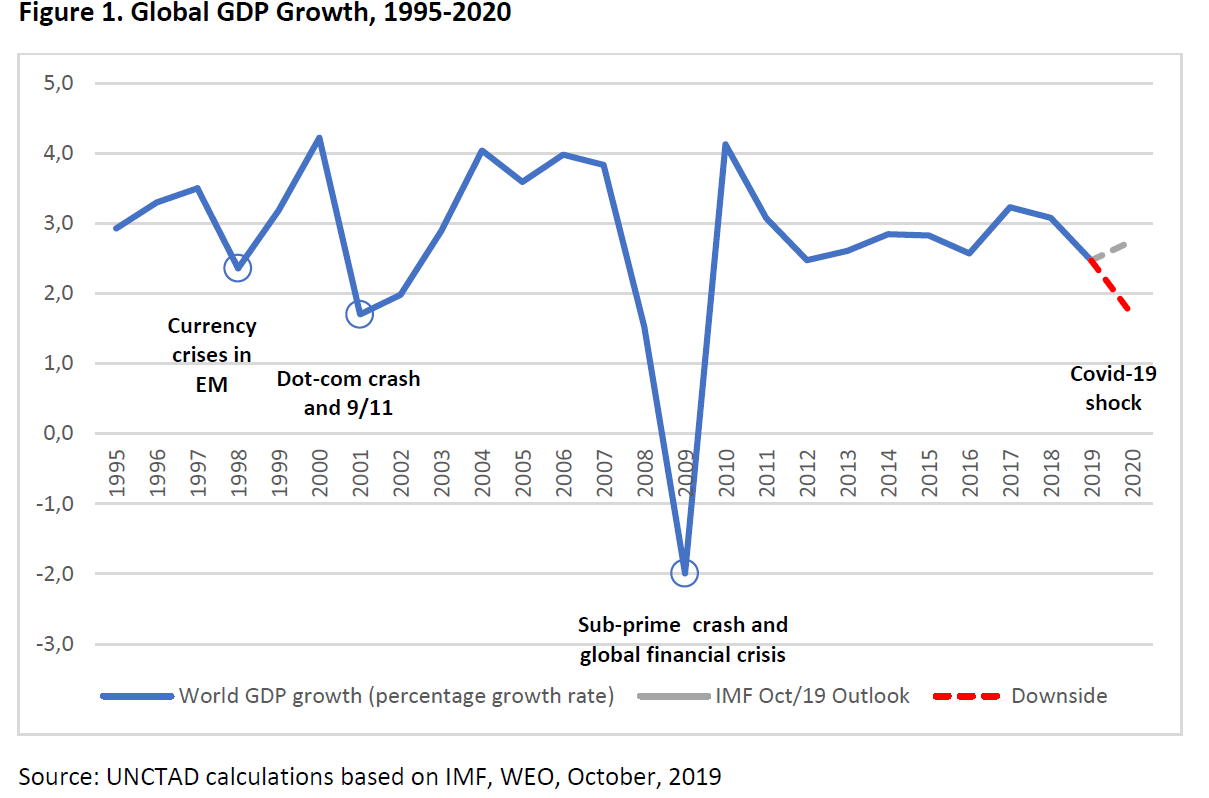

Is there a vaccine or at least a cure that could prevent the global economy from becoming one of the many casualties of the coronavirus outbreak? Uncertainty has hit stock markets and sovereign bond prices, and the eventual impact of the second global economic crisis of this century is difficult to estimate.

However, central banks and governments cannot wait for the dust to settle. They have to take immediate action to mitigate the economic impact of the epidemic.

One week ago, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates for the first time in 12 years, and now the European Central Bank (ECB) is expected to announce unconventional measures on Thursday. Unfortunately, monetary policy alone will not be enough.

The Federal Reserve Board’s decision was unexpected, and it confused many investors. In his weekly newsletter, Erik Nielsen, chief economist of the Italian bank Unicredit, wrote:

“Jay Powell admitted that the rate cut might not have any substantial effect on the US economy, but—apparently—they felt they had to do something to send a signal (but of what?). The problem is that the Fed is now increasingly seen as reacting to the market, rather than guiding the market with its policies; a problem that could easily come back to haunt them going forward.”

In the United States, President Donald Trump has recently clashed multiple times with Fed chairman Jay Powell. In this election year, Trump is counting on stronger monetary support to the American economy to prevent a recession.

In Europe the situation is different, but the recently appointed new ECB president, Christine Lagarde, is now facing a perfect storm: sluggish growth combined with a supply-side shock due to the coronavirus, which together could fuel a potential demand shock.

The ECB has to keep the perfect storm from coinciding with a new banking crisis caused by a combination of weak demand, a credit crunch on small or medium-sized companies, and country-level recessions.

The first important step to avoid such a negative outcome is to postpone the June expiration of TLTRO loans to Eurozone banks. European banks are supposed to repay €222 billion this year on June 20—a strict deadline that could trigger a liquidity crisis.

ECB former vice president Vitor Constancio, in a post on Twitter, outlined a list of possible additional monetary policy measures to prevent the economic shock of the coronavirus from translating into a financial crisis:

- Increased Quantitative Easing, buying private and public debt instruments.

- Unconditional longer maturity liquidity to banks.

- Specific subsidized liquidity lines directed to SMEs lending by banks.

- Supervisors should condone some temporary forbearance regarding evergreening loans to viable firms

On the demand side, fiscal policy is needed to boost consumption and reduce uncertainty. Germany, the fiscal hawk of Europe, has just adopted a €12.4 billion package to help companies affected by the ongoing crisis. The program is designed to support government-subsidized short-term works and to finance public infrastructure projects.

Other countries have more limited fiscal space. Uncertainty is increasing the burden of public debt for countries like Italy, which has been hit hard by the epidemic.

The Italian government reacted with an emergency package of €8.3 billion, but much more will be necessary to face all the consequences both of infection and of the precautionary lockdown of the whole country to limit contagion.

The spread between German bund and Italian treasuries skyrocketed over 200 basis points—a level that would make it extremely expensive to increase public expenditure through the emission of additional debt.

An unpleasant alternative to more deficit spending is still available for Italy.

At the peak of last decade’s financial crisis, in 2012, the ECB introduced an unlimited line of credit for Eurozone members, the so-called Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT). The support from the ECB and IMF would be focused on the shorter part of the yield curve, in particular on sovereign bonds with a maturity of between one and three years.

No single European country has ever applied for OMT because strict conditionalities are attached to financial support. Yet, the very existence of the program has served to reduce volatility and to restore trust in the European single currency. If financial pressure on high-debit countries such as Italy or Greece would increase further, OMT would still be an option to get resources for emergency health care measures.

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), developing countries are even more exposed to financial spillovers of the coronavirus crisis. A fifth of 117 developing countries are highly vulnerable to the direct impact of coronavirus shock due to a combination of different factors: a growing share of public revenues being used to service public debt obligations, high exposure of their economy to trade with China, and low level of reserves to face currency shocks. The insufficient quality of their local health care systems can only contribute further to that impact.

Developed economies are no less exposed to the next stage of problems caused by the coronavirus. The OECD estimates that the global outstanding amount of non-financial corporate bonds reached $13.5 trillion—more than double their real value at the end of 2008. Non-investment grade issuances reached 25 percent of the total.

According to UNCTAD, “while the rapid growth of low-quality corporate debt has become a major concern for advanced economies, by 2018 the share of private debt in overall debt was higher in developing countries—constituting some 73 percent of their total debt—than in advanced economies; as corporate debt in some developing countries is also expanding much faster than investment in physical capital this would suggest a low-quality (or speculative) bias here too.”

It is not too late to do something to limit financial spillovers of the coronavirus outbreak, but the time window is closing. Former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard outlined two priorities:

- Keep the flow of infections down so the health system is not overwhelmed. Do whatever it takes.

- Prepare fiscal measures, including transfers and backstops to banks. Do whatever it takes.

- This is more or less it.

What is still unclear is who will take responsibility for making sure that governments and central banks do “whatever it takes.” In 2012, former ECB president Mario Draghi took the lead.

Will his successor, Christine Lagarde, do the same?

ProMarket is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.