Bernie Sanders is a polarizing front-runner, but there are many reasons to believe the Democratic convention this summer is unlikely to repeat the drama of 58 years ago, when Adlai Stevenson was nominated on the third ballot. The most important is the increasing number of “pledged delegates” chosen on Super Tuesday.

To everything there is a season, including presidential campaigns.

We are nearing the end of the season when political reporters predict there will be an open convention because no candidate is likely to win a majority of delegates needed to secure the nomination. Typical is a piece that appeared in The New York Times on Sunday, quoting a moderator of the recent Nevada debate, Chuck Todd: “There’s a very good chance none of you are going to have enough delegates to the Democratic National Convention to clinch this nomination.”

At even money, it would be worth betting against Mr. Todd, because there have been no multiple ballots to choose a Democratic presidential candidate since 1952. There are reasons to believe the Democratic convention in Milwaukee this summer is unlikely to repeat the drama of 58 years ago, when Adlai Stevenson was nominated on the third ballot.

The reasons are a long-term move to primaries, changes in their timing, and a back-and-forth fight over the role of automatic, unelected delegates. These changes grow out of decades of struggles within the Democratic party, each party rule a seeming artifact of one fearsome fight or another.

More Delegates

Perhaps the most important long-term trend is the increasing number of pledged delegates chosen on Super Tuesday, which this year takes place on March 3. A pledged delegate is one who supports a particular candidate. At 1,357, more pledged delegates will be chosen on this day than ever before, fully one of every three among the 3,979. A big part of the increase is from California, which moved up the selection of its 415 pledged delegates to March from June.

A really big winner could close fast on the 1,991 votes needed to win the nomination, even if opponents win some delegates by getting 15 percent or more in state contests. The compressed timetable favors the leading candidate, Bernie Sanders, who virtually tied Pete Buttigieg in Iowa and won in New Hampshire and even more persuasively in Nevada.

The few states that retained caucuses, which dwindled to six from 14 in 2016, choose a minuscule number of delegates. Caucus meetings are held at sometimes-obscure times and places, with far lower voter participation than primaries. They are notorious for problems, as this year’s Iowa caucuses reminded us.

Superpowers Gone

Another reason there may be only one ballot was a move that stripped so-called “super delegates” of their superpowers, which were to vote for any candidate they wanted. These 771 automatic delegates, including Democratic senators, governors, members of Congress, and party officials, are barred from voting on the first ballot if it will change the outcome. Only if the convention goes to a second ballot can their votes make a difference.

This is not the first time party officials have had their power stripped. After the tumult of the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Sen. George McGovern headed a reform commission that won the elimination of the wholesale granting of delegate badges to federal and state elected officials and party workers. Delegates were to be chosen exclusively through caucuses and primaries open to every Democrat. The result was that many first-time delegates were selected in 1972 and most Democratic members of Congress skipped the convention.

The elimination of unelected delegates opened the way for the nomination of a candidate from the left, who was McGovern himself, campaigning to end the war in Vietnam with the slogan Come Home, America. He lost the general election to the incumbent, Richard Nixon.

Party and elected officials were restored as ex officio delegates in 1984 and gave Walter Mondale the final push he needed to declare, in June of that year, that he had enough delegates for the nomination in his race against Sen. Gary Hart.

Changing Rules

And that’s how things stayed until after the 2016 election when Sanders complained that superdelegates had acted in a way that frustrated the will of primary voters. Rules were changed yet again and, like McGovern, a candidate on the left looks to benefit from a change he authored. Ex officio unpledged delegates cannot stand in Sanders’s way on a first ballot.

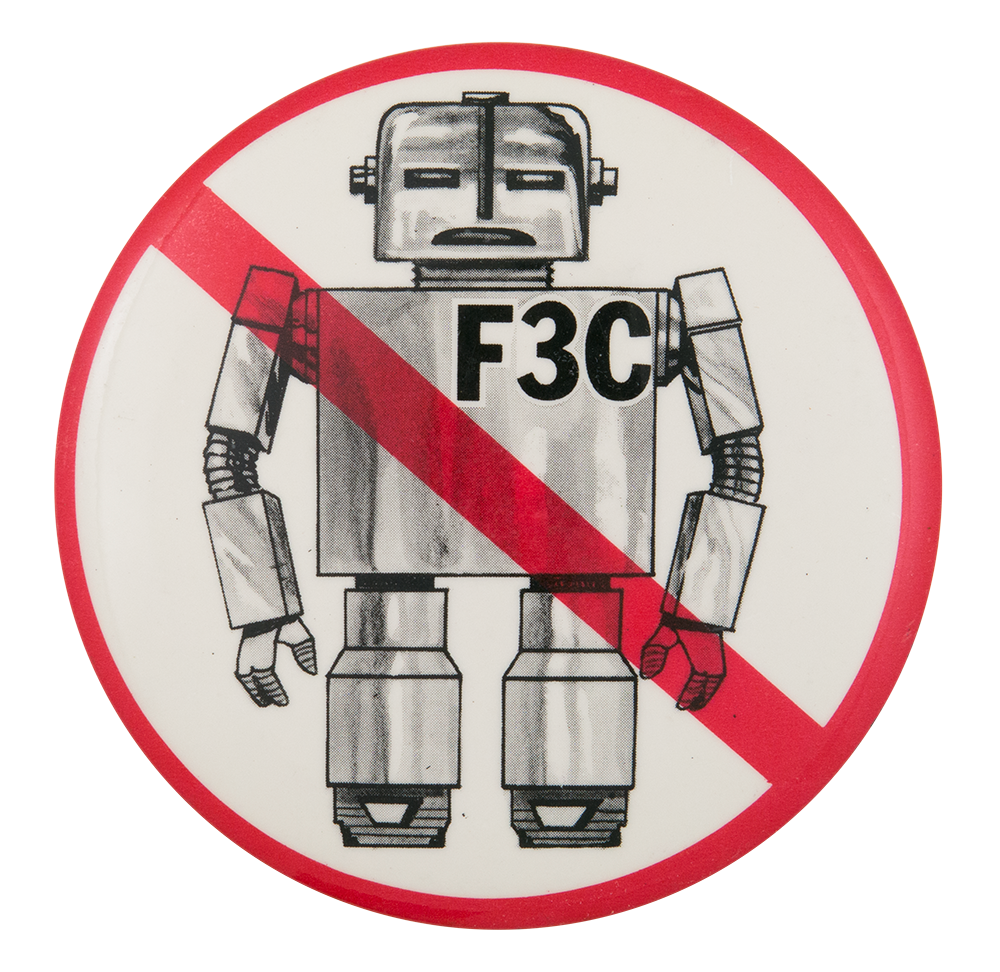

But then, there is another rule to take into account, which goes back to the 1980 convention. Many attending thought incumbent President Jimmy Carter would lose, as in fact he did to Ronald Reagan, and some wanted to switch their votes to Sen. Ted Kennedy. They were barred by Rule F3C, which bound them to support their pledged choice on the first ballot. They protested, waving signs that said they did not want to be robots.

The result was another change. Today, Rule C7E in chapter IX of the 2020 Call for the Convention, allows delegates to vote on every ballot for “the candidate of their choice whether or not the name of such candidate was placed in nomination.” Theoretically, delegates pledged to Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren or anyone else could choose at the last moment to vote for someone else, like Michael Bloomberg.

But don’t bet on that one.

David Lawsky covered presidential elections through the year 2000, and was the delegate counter for UPI in 1984 when his count was preferred by most news organizations. Lawsky also worked for two decades as a journalist for Reuters in Washington, Brussels, and San Francisco.

The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.