Antitrust regulators should stop mergers where a firm owning the means of transmission acquires a provider of content. The people that own the pipes shouldn’t also own the water. As the Supreme Court stated in 1945, “Freedom to publish is guaranteed by the Constitution, but freedom to combine to keep others from publishing is not.”

It is time for antitrust regulators and judges to take a hard look at media mergers, which threaten not only competition but also freedom of expression. Numerous news reports and op-ed columns have referred to or urged a revival of antitrust enforcement to counter the increasing market power of tech giants such as Google, Microsoft, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon. As a practicing antitrust lawyer approaching my 50th year in antitrust, I applaud this renewed interest, although I think it seriously underestimates the difficulty of actually achieving enforcement against these behemoths.

The problem is the transformation of antitrust from laws originally intended to protect against undue concentrations and abuses of economic power into laws that now serve to protect such concentrations and abuses. Prime examples include permissive merger enforcement, the presumed legality of vertical restraints like resale price maintenance, and numerous procedural hurdles for private plaintiffs like enhanced pleading standards. The result is sadly a classic case of regulatory capture, where those supposedly subject to regulation are now in control of the regulators.

As for mergers, regulators at the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission allow industries to consolidate to oligopoly status, at which point conscious parallelism allows coordinated price increases to be implemented. These are immune from antitrust enforcement because there is no actual agreement, in that the oligopolists are simply monitoring and following each other.

There is a simple preventive action that regulators could take to prevent this—prohibit the mergers in the first place. Indeed, apply a presumption to prospective mergers that if companies propose to merge in an industry that may permit price increases through conscious parallelism, the merger will not be allowed. This is in fact what the Supreme Court used to do through the 1960s before Chicago School economics took over and advocated for a strong anti-regulatory, pro-market bias that was eventually adopted by regulators, judges, and academics.

All this market concentration and curtailment of enforcement have largely been the result of faux-free-market economics championed by economists and judges espousing what I term the “myth of the market”—that unregulated markets will remedy all competitive abuses through new entry in response to monopoly rents and supra-competitive prices.

A second strand of this argument rests on a misrepresentation of the purpose of the antitrust laws at the time of their passage in 1890 (Sherman Act) and 1914 (Clayton Act): that Congress passed these laws to protect consumers rather than competitors. Without competitors, of course, there can be no competition. In order to turn antitrust enforcement around, both of these sacred cows will have to be gored.

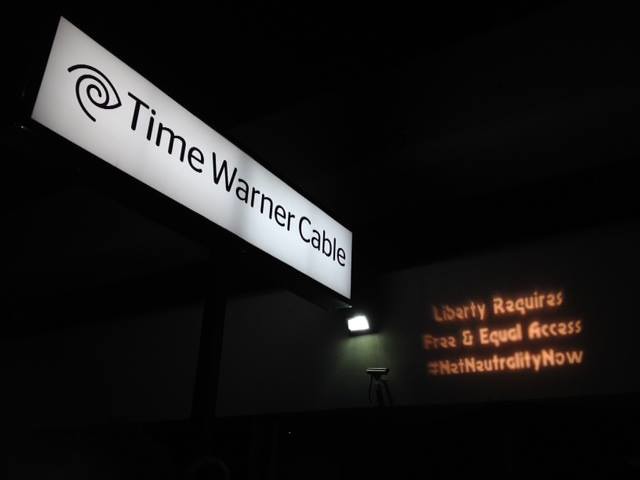

There is one area of particular concern, in which I believe regulators have seriously failed to recognize and pursue a ground for preventing mergers that pose a serious threat not only to competition, but to the underpinnings of democracy. This involves media mergers where a firm owning the means of transmission acquires a provider of content, e.g., AT&T-Time Warner and Comcast-NBC Universal.

In each of these mergers, a dominant firm in the broadcasting business acquired a major producer of programming. These mergers are generally characterized as vertical, in that the merging firms are at different levels of the distribution system, arguably in different markets, and thus not competing with each other. Regulators are much more likely to approve such vertical mergers, unless there is strong evidence that the merger will result in substantial foreclosure of competitors to bring their products or services to consumers.

What regulators have failed to appreciate is that such media mergers represent the confluence of antitrust laws and the First Amendment. The former protects competition, the latter freedom of expression and access to information. For this reason alone, such mergers should receive the strictest scrutiny, even with a presumption against their legality under the antitrust laws. Simply put, the people who own the pipes shouldn’t also own the water.

When the owner of transmission facilities acquires a content provider, there is a dangerous probability that 1) the transmission company will not permit content from the acquired company that conflicts with its political views; 2) the transmission company will foreclose competitors of the acquired content company from access to its transmission facilities, or impose onerous economic terms or content restraints; 3) other content providers will be denied access to transmission facilities; and 4) the public will be deprived of access to information and content it would otherwise have.

| “To use the freedom of the press guaranteed by the First Amendment to destroy competition would defeat its own ends.” |

Such mergers thus represent a threat not only to competition but also to the free and unfettered exchange of information and ideas vital to democracy.

Nor is this a radical new legal approach to antitrust. The US Supreme Court has been conscious of the interplay between antitrust and the First Amendment since its decision in Associated Press v. United States in 1945, when the Supreme Court struck down a wire service’s bylaws that excluded non-member newspapers from access. When the wire service claimed that the First Amendment protected its conduct, the Supreme Court responded that “The First Amendment, far from providing an argument against application of the Sherman Act, here provides powerful reasons to the contrary.”

The Court added, “Freedom to publish means freedom for all and not for some. Freedom to publish is guaranteed by the Constitution, but freedom to combine to keep others from publishing is not.” Furthermore, “The First Amendment affords not the slightest support for the contention that a combination to restrain trade in news and views has any constitutional immunity.”

Similar concerns appear in later Supreme Court decisions such as Citizen Publishing v. United States in 1969 and Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo in 1974. As the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit said in Kansas City Star Company v. United States, (8th Cir. 1957), “A monopolistic press could attain in tremendous measure the evils sought to be prevented by the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. Freedom to print does not mean freedom to destroy. To use the freedom of the press guaranteed by the First Amendment to destroy competition would defeat its own ends.” Antitrust regulators and judges should take these words to heart, especially today.

Daniel R. Shulman has been chief counsel in antitrust litigation involving major industries in a variety of cases since 1970 ranging from data storage, media, food, oil and gasoline, airlines, consumer electronics, medical electronics, health care, thoroughbred horses, and many other areas. He is based in Minneapolis.

The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.