The President’s behavior provides direct evidence of how political power is used to advance personal goals. It has also had the unintended consequence of exposing the depth of the institutional corruption present in Washington

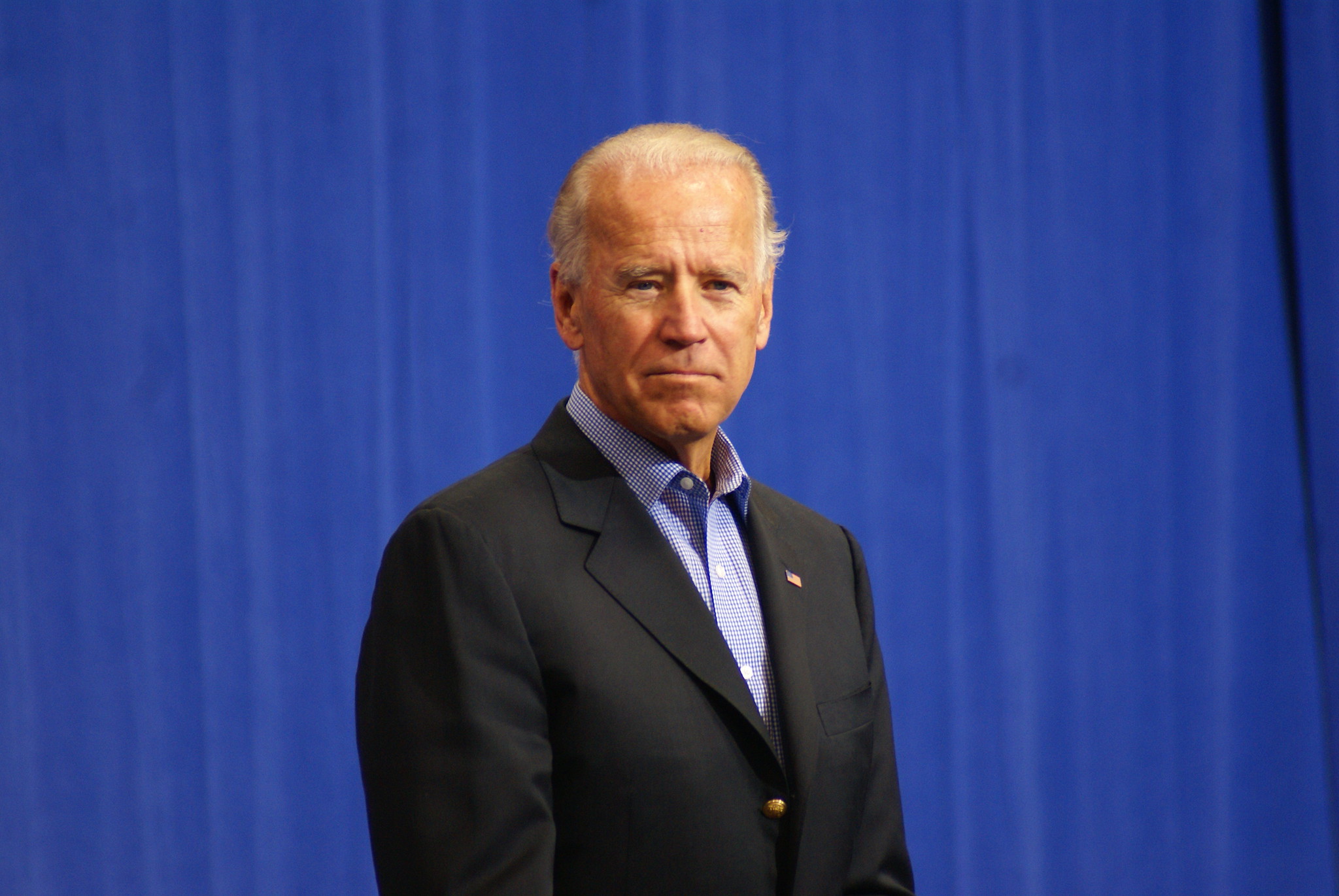

As a candidate, Donald Trump promised to “drain the swamp.” As a president, he seems to have flooded that swamp more than drain it. His behavior provides direct evidence of how political power is used to advance personal goals. It has also had the unintended consequence of exposing the depth of the institutional corruption present in Washington. His obsession with Hunter Biden is a prime example. The fact that most of the press downplays these conflicts of interest suggests that in Washington they are not only tolerated, but widely accepted as the status quo.

Institutional corruption is “an influence that illegitimately weakens the effectiveness of an institution.” One of the mechanisms that enables institutional corruption is the phenomenon of revolving doors: politicians or bureaucrats who move from investigating or regulating a company to working or lobbying for that company. Earlier this week, the Stigler Center hosted two lectures on this topic, which illustrated this phenomenon very well. Yet to date, the academic literature seems to have ignored the effect of familial revolving doors. For this reason, we have collated different accounts of the Hunter Biden story to shed some light on an important phenomenon that seems to be widely diffused in Washington.

During President Obama’s second term, Vice President Biden was the Administration’s front man in Ukraine. In February 2014, when the pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych resigned, Biden was very active in supporting the new government. In May of that year, the gas company known as Burisma Group appointed Hunter Biden, the vice-president’s son, to its board. Burisma was no ordinary company: it was the creation of Mykola Zlochevsky, a long-time supporter of Yanukovych, who—when his friend became president—was appointed natural resource minister in spite of his conflict of interests.

According to a Guardian investigation, “Zlochevsky owned his businesses via Cyprus, a favored haven for assets unobtrusively controlled by high-ranking officials in the Yanukovych administration.” The Guardian reports that during Zlochevsky’s mandate, Burisma “gained nine production licenses and its annual production rose sevenfold.”

In March 2014, the UK government froze $23 million that Nicolay Zlochevsky was trying to move from London to Cyprus. “‘The message is clear,’ former British Prime Minister Theresa May said, ‘we are making it harder than ever for corrupt regimes or individuals around the world to move, hide and profit from the proceeds of their crime.’”

Following the Yanukovych years, under new President Petro Poroshenko, Ukraine’s prosecutor general Viktor Shokin investigated both Zlochevsky and Burisma. According to a May 2019 story by the New York Times, “among both Ukrainian and American officials, there is considerable debate about whether Mr. Shokin was intent on pursuing a legitimate inquiry into Burisma or whether he was merely using the threat of prosecution to solicit a bribe, as Mr. Zlochevsky’s defenders assert.”

In the midst of Shokin’s investigation, Burisma appointed Hunter Biden to its board. Why did Hunter Biden, who was not an expert on either the Ukraine or the energy sector, join such a controversial company?

According to a May 12 Burisma press release, Biden was appointed to lead the “holding legal team’” despite his lack of experience in this area. At the time, Hunter Biden was a partner of Rosemont Seneca, an investment consulting firm co-owned by Christopher Heinz and Devon Archer. Heinz is the stepson of Senator John Kerry—the US Secretary of State at the time. According to financial records disclosed in a Manhattan federal court in an unrelated case against Archer, between April and October of 2014 Burisma paid more than $3 million to an account linked to Rosemont Seneca.

Perhaps Zlochevsky was not worried about the prosecutor general’s investigation of Burisma, as Joe Biden’s defendants argue. Nevertheless, it’s hard to consider it a mere coincidence that Zlochevsky—after losing his main political sponsor—would decide to hire both the son of the US Vice President—then in charge of the crisis in the Ukraine—and the stepson of the US Secretary of State.

Vice President Biden is not his adult’s son keeper. In 2019, when Joe Biden was already in the running for the 2020 US presidential elections, Hunter told the New York Times that, “at no time have I discussed with my father the company’s business, or my board service, including my initial decision to join the board.” Two months later, Hunter Biden told the New Yorker the opposite, admitting that in December 2015, he had in fact discussed the Burisma situation with his father: “Dad said, ‘I hope you know what you are doing,’ and I said, ‘I do.’”

At what point should Hunter’s behavior impact his father’s actions? Once Joe Biden knew that his son was doing business with a controversial company in Ukraine he should have recused himself from dealing with the country. Not only did he fail to do so, but he seems to have contributed to the ousting of the very prosecutor that was investigating the company that had hired his son.

At the end of 2015, Joe Biden visited Kiev and delivered a speech against corruption, which he said was eating Ukraine “like a cancer.” Two months later, the Ukrainian Parliament ousted Shokin as Prosecutor General. Is there a connection between these two events? Listening to Vice President Biden’s own words, it would appear so.

During a 2018 event sponsored by the Council of Foreign Relations, Biden recalled his role in the Ukrainian government’s decision to fire the prosecutor who was investigating the company Hunter Biden worked for:

“I remember going over (to Ukraine), convincing our team … that we should be providing for loan guarantees. … And I was supposed to announce that there was another billion-dollar loan guarantee. And I had gotten a commitment from (then Ukrainian President Petro) Poroshenko and from (then-Prime Minister Arseniy) Yatsenyuk that they would take action against the state prosecutor (Shokin). And they didn’t. …”

“They were walking out to a press conference. I said, nah… we’re not going to give you the billion dollars. They said, ‘You have no authority. You’re not the president.’ … I said, call him. I said, I’m telling you, you’re not getting the billion dollars. I said, you’re not getting the billion. … I looked at them and said, ‘I’m leaving in six hours. If the prosecutor is not fired, you’re not getting the money.’ Well, son of a bitch. He got fired. And they put in place someone who was solid at the time.”

What happened to the anti-corruption investigation on Burisma? According to the case file and current General Prosecutor, Yuriy Lutsenko, the file passed to a different Ukrainian agency, closely aligned with the US Embassy in Kiev, known as the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU). NABU closed the case after just a few months.

In February 2017, a Burisma press release celebrated the end of all the company’s troubles:

“Until recently, there were open criminal proceedings against Burisma on suspicion of tax evasion of UAH 1 billion, however, the case was closed in January 2017 after the company had paid off UAH 180 million of taxes.

In September 2016, the Pechersk District Court of Kiev obliged the Prosecutor General’s Office to close the case against Nikolay Zlochevsky and remove him from the wanted list. The PGO fulfilled the relevant court decision, as reported Burisma.”

It’s possible that the Burisma case, as many others, had been dormant for too long, as the UK and US governments have complained. Moreover, it’s also possible (in fact, likely) that Vice President Joe Biden’s actions contributed to removing a corrupt prosecutor and to stimulating more effective anti-corruption enforcement. Yet, knowing that Vice President Biden had the power to fire a prosecutor, wouldn’t the new prosecutor be reluctant to investigate a company where his son was employed? Is this the real reason Burisma hired Hunter Biden—despite the fact that he did not have any relevant expertise? This is precisely the way in which familial revolving doors undermine public trust in institutions.

The Ukraine prosecutor general, Yuri Lutsenko, told Bloomberg on May 16th that neither Joe or Hunter Biden are subject to any current investigation in Ukraine, despite the constant interest in this issue expressed by President Trump’s personal attorney, Rudolph Giuliani, which prompted the intelligence whistleblower’s complaint.

Joe Biden didn’t break any law, but what his behavior reflects about Washington is not reassuring. His decisions during the Ukraine crisis not only directly impacted US foreign policy, but also the company his son was working for. He should have asked his son to step down from the Burisma board or otherwise recused himself from handling Ukraine. Not only did he fail to do so, but he seems completely unapologetic about the actions he took.

Having both grown up in Italy, we are sensitive to the phenomenon of the familial revolving door and its capacity to devastate public trust in democratic institutions. We are sorry to find out that this problem is alive and well in Washington as well. The time has come to expose it fully and begin to eradicate it.

The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.