The rise of giants like Amazon and Facebook proves the long-lasting influence of Director’s approach. His intellectual and political legacy is the transition of legitimacy from democratic institutions as the locus of governing power to private monopolies.

September 11, 2019, was the 15th anniversary of the long and productive life of one of the most important men Americans have never heard of, the political philosopher and economist Aaron Director. Director is the key founder of what is now known as the Chicago School of law and economics, which reshaped the American approach to corporate power and political economy.

I didn’t know Director, but I know his work because of the world in which we live. His handiwork is in the air we breathe, the language we use, and the policies that we consider possible. It is in our markets, our banks, our corporations, the products we can buy and sell, and even the wars we may yet have to fight. So before evaluating his life, let us bow before this truly great man. Great not in a moral sense, but in a raw sense of impact.

Director’s life was dedicated to setting free the power of concentrated capital, eliminating the power of labor, and undoing the New Deal. His success is so profound it is hard to describe, so embedded are we today in the world and rhetoric Director shaped.

America, when Director began learning economics, was a New Deal country, a land that sounds foreign to our ears. The idea one could earn billions of dollars was not just immoral, but increasingly inconceivable. Walter Lippmann wrote about John D. Rockefeller in 1937, “Before he started his enterprises, it was not possible to make so much money; before he died, it had become the settled policy of this country that no man be permitted to make so much money. [Rockefeller] lived long enough to see the methods by which such a fortune can be accumulated, outlawed by public opinion, forbidden by statute, and prevented by the tax laws.”

These words were more than just rhetoric. In the post-war era, Republican President Dwight Eisenhower mocked anyone who might want to return to a world of hyper-wealthy business leaders and desperate citizenry. “Among them are a few other Texas oil millionaires and an occasional politician or businessman from other areas,” he wrote. “Their number is negligible, and they are stupid.”

Roughly a third of workers were unionized. Nearly every large company, from General Motors to General Electric, was under antitrust investigation or prosecution by the federal government. The Attorney General called 1955 the “year of antitrust.” Banks were strictly controlled, with the largest banks in New York City prohibited from even opening branches outside of the five boroughs.

This situation was accepted by business leaders. In 1946, the head of the US Chamber of Commerce said, “Labor unions are woven into our economic pattern of American life, and collective bargaining is a part of the democratic process. I say recognize this fact not only with our lips but with our hearts.” Bitter strikes were a thing of the past.

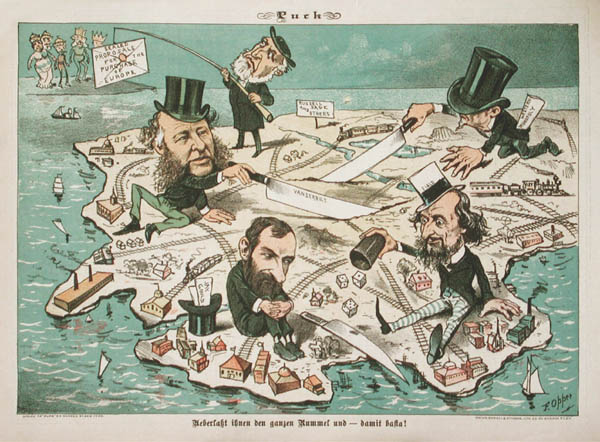

Monopoly power and plutocracy were forbidden for good reason; Americans saw concentrated corporate power as proto-fascist. In 1943, FDR’s attorney general Francis Biddle had blamed the rise of fascist dictators and the recent world war partially on concentrated corporate power. “When the industrial life of a country passes into the hands of relatively a few individuals,” he said, “their power over the direction of public affairs exceeds the power confided by the people to their elected representatives in the government itself.”

So in 1946, when Director started what was first called the Free Market Study at the University of Chicago, his project was disdained, even hated by the liberal establishment. “The phrase Chicago Economics was often uttered with the same contempt that commonly characterized unsavory ethnic and religious epithets,” wrote Chicago Schooler Henry Manne. But Director was a relentless evangelist. As Director’s protege Robert Bork said about him, “A lot of us who took the antitrust course, or the economics course, underwent what can only be called a religious conversion.” Over the course of decades, Director and his acolytes gradually transformed what seemed to be an unwinnable quixotic cause of returning billionaires to their rightful place into what today seems so entrenched that radical inequality is understood as the eternal foundation of America’s economic system.

By 1980, as Director’s best friend George Stigler put it, Director’s ideas had “conquered the field,” as the old antimonopoly framework disappeared from the economic literature. Unionization rates collapsed over the next two decades. Even Democrats and liberals, everyone from Bill Clinton to Stephen Breyer to Ruth Bader Ginsburg, embraced, whether they knew it or not, a pro-concentration framework which became known as the “New Learning” about antitrust.

This has culminated today in the rise of giants never seen before in this world, accompanied by a radical new conception of the role of the business leader. Just a few years ago, in stark contrast to Biddle’s warning, Mark Zuckerberg openly bragged, “In a lot of ways Facebook is more like a government than a traditional company.” This transition of legitimacy from democratic institutions as the locus of governing power to private monopolies and financial institutions is Aaron Director’s intellectual and political legacy.

How did he do it? And why? Director wrote very little, and has an extremely sparse archive.

Mencken’s Elitism

The story starts with Director’s upbringing in Portland, Oregon, one of the most racist and intolerant cities in America outside of the South. Director came from Russia as a 13-year old, and his family was Jewish. Enduring slurs from classmates on a regular basis, Director got a scholarship to Yale, where he found the Anglo-Saxon WASP establishment equally maddening. In college, he turned for inspiration to the greatest cynic of the time, H.L. Mencken, a strangely authoritarian and brilliant elitist with a penchant for beautifully written satire.

Director greatly admired Mencken. At Yale, for instance, at a satirical newspaper Director anonymously published called The Saturday Evening Pest, he and his friends used mockery and elitism to attack the apathetic student body around them, writing that “the definition of the United States shall eternally be H. L. Mencken surrounded by 112,000,000 morons.” Director called for “an aristocracy of the mentally alert and curious” to lead, displaying the elitism that would become his lodestar. Director became a thoughtful and somewhat mysterious man with a deep lack of faith in human beings to govern themselves. His attitude wasn’t necessarily unreasonable; the 1920s was a horribly anti-Semitic decade in the United States. Being Jewish and working through academic institutions in that era was practically a lesson in how Americans could be intolerant and a warning regarding the dangers of majoritarian rule.

Director would ideologically shapeshift over his lifetime. He was a radical socialist in the 1920s under the influence of the Wobblies and Thorstein Veblen and a conservative antimonopolist in the 1930s. He was eventually recruited to run the Free Market Project at the University of Chicago by conservative antimonopolists Henry Simons and Friedrich Hayek after World War II.

Director made his final turn in 1950. Simons and Hayek both saw corporate monopolies as dangerous, perhaps even more dangerous than big government or labor unions. And Director was a great admirer of Simons, whose Positive Program for Laissez Faire was as antimonopoly as it was anti-big government. But Simons killed himself in 1946. And the extreme right-wing funder of the project, Harold Luhnow of the Volker Fund (who later dallied with fascists in the 1960s), essentially threatened to fire Director if he didn’t jettison his allegiance to Simons’s anti-corporatist ideas.

Director suddenly decided that conservative ideas were compatible with corporatism after all. Monopolies, apparently, were always created by government. At this moment, Director broke with the conservative tradition and birthed neoliberalism, the anti-government, pro-monopoly philosophy that now dominates policymaking globally. Director convinced George Stigler and Milton Friedman of the new creed. Both had opposed corporate monopolies, but flipped to support Director’s new movement. The Chicago School was born.

Throughout this ideological journey, Director remained a Mencken-ite above all, a man who believed that some were fit to rule, and others to be ruled. He didn’t characterize it this way, instead using the term ‘economist’ to mean those fit to speak the language of power. But that was his framework, and in many ways, it is still the framework by which antitrust insiders think about who gets to have opinions in dialogue about political economy.

Director organized the Chicago School rhetorically in two ways. He framed the idea of law and economics as that of bringing disinterested science to law and removing law from the messy realm of democratic politics. His was the realm of pure logic and evidence. And in keeping with the Mencken tradition, Director organized mockery of liberal elites, who he felt, accurately, would be susceptible to being intimidated by the mathematized jargon of right-wing economic models.

“The ambition of Director,” as George Priest wrote, “was essentially to ridicule the Supreme Court’s treatment of antitrust as well as of other forms of government interference with the market.” Director would find a young scholar and stake that person with money and support, encouraging him to blow up an important precedent or concept.

The Standard Oil Case

The best example of Director’s method was how he destroyed the predatory pricing doctrine, which was a key linchpin of antitrust enforcement. Prior to Director’s handiwork, it was commonly understood that one of Standard Oil’s tactics was selling oil at a loss in certain markets until the corporation could drive its competitors out of business. The company could cross-subsidize temporary losses from elevated monopoly prices in other markets.

In 1953, Director encouraged a student to revisit this case. He said this kind of power play was illogical. If Standard Oil were losing money in a regional market, a competitor could simply borrow money to compete with Standard Oil, or withdraw from the market, and re-enter when the predatory behavior stopped. Below-cost pricing to gain market power was just very unlikely to happen in free markets, according to Director.

Director tasked John McGee, a student, to study the Standard Oil case. And lo and behold, McGee found that despite what “everyone” thought, there was, in fact, no evidence of predatory pricing in the trial transcript. McGee published his ground-breaking essay in 1958, in a journal of law and economics founded by Director. In 1975, liberal Democrat Donald Turner and his partner Phillip Areeda published a key article on predatory pricing, accepting McGee’s rationale. (It didn’t hurt their motivations, of course, that they were both on the payroll of IBM, which was at that moment in a bitter series of antitrust lawsuits which included, you guessed it, predatory pricing claims.) With support on the right and the left, courts soon accepted Director’s ideas, laundered through McGee, Turner, and Areeda.

Today, Director’s colleagues illustrate this as a brilliant example of pure logic undercutting a staid and false conventional wisdom. But of course, McGee’s findings were wrong. Reviewing the Standard Oil case and the McGee article decades later, Chris Leslie showed that McGee cherry-picked and ignored evidence to make his claim. Standard Oil had engaged in predatory pricing. Contra Director’s logic, predatory pricing is quite rational. A competitor to a corporate goliath can’t borrow an infinite amount of money to lose until prices come back, nor can a competitor just shut down until prices go back up. No bank would lend to a competitor of Standard Oil, just as no one today will lend to a retailer competing to lose money against Amazon. Aaron Director’s icy logic and expertise were, as it turns out, absurd. But in true Mencken-like fashion, the goal was rhetorical, to build pseudo-scientific arguments that would intimidate fancy liberals against using common sense. Director knew his audience.

There are reasons Director succeeded that have nothing to do with him. Director’s project took advantage of the increasing elitism of the liberal world in the post-war era. The attack on the antimonopoly tradition started on the left, by men influenced similarly by Thorstein Veblen and Mencken, men like Richard Hofstadter and John Kenneth Galbraith. The New Deal slowly rotted, and the only people who had answers were Director and the men he trained.

Director’s impact is undeniable. I started out researching Director’s role in the rise of law and economics with a belief that there was a good faith attempt to wrestle with flaws in what perhaps was an overwrought New Deal structure. But what I realized, after seeing how he constructed a brilliant political movement to attack the ability of democratic institutions to touch economic questions, is that Director modeled himself after Mencken. He was a nihilist and an elitist, and so was his movement.

Today’s America, where lifespans are declining, where giants like Google and Amazon stride across the land unchallenged, where big banks crush the economy and bring forth men like Donald Trump to lead, is Director’s legacy. It is a legacy of nihilism and hopelessness. I admire his stunning ability to build political power and transform society. But truthfully, I could never really understand why he sought to use them towards such wretched ends.