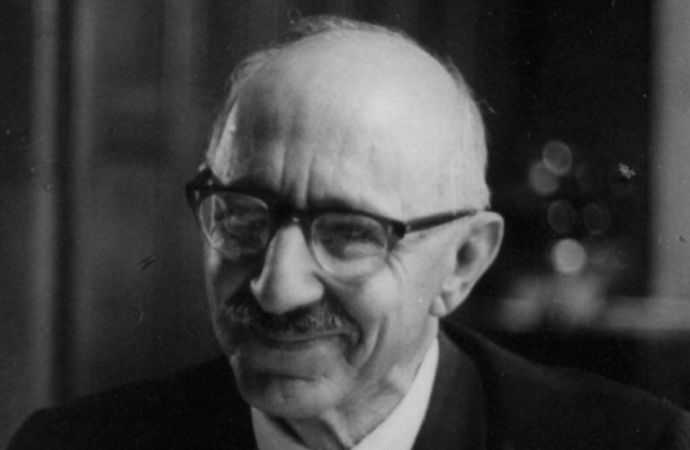

Aaron Director died 15 years ago. He published almost nothing, but his ideas influenced a generation of economists and intellectuals. Professor Stephen Stigler remembers the most enigmatic founder of the so-called “Chicago School”.

The faculty of the University of Chicago Law School is, and has been for some time, an extraordinary group. Aaron Director was unusual even within this group. In a group where the average annual number of publications per single faculty member exceeds that of the whole of many law schools, Aaron published next to nothing—a coauthored book and a pamphlet on unemployment in 1932 before he hit his stride and little more than a few book reviews after that.

In a group decorated by all manner of academic honors (even a Nobel Prize), Aaron did not even have a Ph.D. In a group of forceful and dynamic intellects, Aaron never raised his voice, and casual observers might well have overlooked him, unless they noticed his colleagues lowering their own voices to hear what Aaron had to say.

And of course he was remarkable, or we would not be recalling him 40 years after he retired and moved to California, where he lived until his death in September 2004. A reader would be entitled to ask, what can I, a statistician who came to Chicago 14 years after Aaron left for California, what can I usefully add to a discussion of this remarkable man?

I could tell you that I am writing because in the early 1930s Aaron taught statistics at this university. He did do that, but that is not the real reason, which derives from the fact that my father, George Stigler, was, from the late 1950s until he died in 1991, Aaron’s best friend.

My father and Aaron first became closely acquainted in 1947 when they were invited (with Milton Friedman, already by then Aaron’s brother-in-law) to the first meeting in Switzerland of the Mont Pelerin Society. In pictures from that time they look like three mischievous East German spies. That society was formed by Friedrich Hayek to celebrate classical liberalism, and Aaron had met Hayek in 1937 during a year-long stay at the London School of Economics. Aaron played a pivotal role in getting the University of Chicago Press to publish Hayek’s influential 1944 attack on government intervention in economic affairs, a book called The Road to Serfdom.

When my father returned to the University of Chicago in 1958, he and Aaron and Milton were reunited on one campus, and they shared an extraordinary level of discourse, and lighter moments as well. When Milton visited the USSR, he sent my father a postcard with a picture of Karl Marx. My father was chagrined that he had no comparable postcard of Adam Smith to respond with.

He and Aaron went to remedy this and learned something about practical price theory in the process. First, postcards were printed in sets of five, so they had to identify four more worthy subjects to go with Adam Smith. And second, while it cost $100 to produce 100 sets of postcards, it cost only $101 to produce several thousand sets. I still have a cabinet full of the results of this lesson. They had other adventures in practical economics, including an ill-timed entry into the silver futures market, which was even less profitable than the postcard venture.

After Aaron retired from the University of Chicago in 1965, my father began a long series of academic visits to Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, where the chance to visit with Aaron was a distinct highlight. It was only in the early 1980s that I got to know Aaron more than casually.

Despite a 40-year difference in our ages, I was attracted by the same economics, written at the tender age of 20. It bears the hallmark of Aaron’s keenly analytical mind and is entitled “Blue Sunday Madness.” At that time, a “Blue Sunday” law was being considered in Portland, one that would ban work on Sunday and, among other things, halt all trains on Sundays.

Rather than attack the proposed law, Aaron examined its consequences. He began by imagining a train approaching Portland on a Sunday and stopping 7 miles out of town, where the conductor informed the passengers they would remain there until Monday. Aaron granted that in olden days the law would work no hardship—“The nomads of old,” he wrote, “marching through the wilderness, might without any disadvantages stop marching on Sunday. They might also feed their cattle on Saturday and tell them they must go hungry on Sunday. They could also feed themselves and diplomatically inform their stomachs that eating on Sunday was work and therefore forbidden.”

Aaron allowed that similar accommodations were feasible in the modern age and that some relief was available by the planned exemption of automobiles from the law. “You may ask,” he wrote, “why Fords are allowed to be used on Sunday while trains are not. Every Ford owner will inform you that Fords carry special privileges, as it takes no work to drive one.” But in industry and shipping and communications, he noted that more serious economic consequences would be encountered, such as shutdown costs in heavy industry, boats forced to stop on Sunday regardless of the wind, and the need to recall wireless transmissions that would otherwise arrive on Sunday. Still, he ended on an optimistic note: if the law were approved it would still be possible, he said, to “live—if not happily at least live ever afterward.”

Aaron graduated from Lincoln High in January 1921, and about that time the Yale University dean of admissions visited the school, with the result that Aaron and a slightly younger friend enrolled in Yale in the fall of 1921 as scholarship students. The younger friend was Mark Rothkowitz, later famous as an abstract painter under the name Mark Rothko. While at Yale, Aaron and Mark Rothko published an underground newspaper called the Saturday Evening Pest from February to May 1923. Its motto was, “The beginning of doubt is the beginning of wisdom,” and the first issue announced this credo:

We believe

That in this age of smugness and self-satisfaction, destructive criticism is at least

as useful, if not more so, than constructive criticism.

That Yale is preparing men, not to live, but to make a living.

That the life of the average undergraduate is stupid, empty, and meaningless.

That the literature of the undergraduate consists chiefly of our contemporary, The

Saturday Evening Post.

That athletics hold a more prominent place at Yale than education, which is endured

as a necessary evil.

They evidently came under fire from the administration; their last issue contains a supporting letter solicited from Sinclair Lewis, a distinguished alumnus of Yale. Rothko did not return the next fall, and Aaron graduated in 1924 after only 3 years, probably to the relief of the Yale administration.

Aaron was a bit of a radical at Yale, and for the next year and a half he traveled, working as a migrant laborer in Midwestern wheat fields and New Jersey textile mills, even in a Pennsylvania coal mine, as he crossed the country studying American labor from the inside. He taught at a labor college in New Jersey, and he traveled to Europe, to England, and as far to the east as Czechoslovakia, before returning to Portland as an educational director at the Portland Labor College.

In 1927, he decided to come to Chicago for graduate study in labor economics with Paul Douglas, then a member of our economics department and later a US Senator from Illinois. After 3 years as a student, Aaron joined the staff in 1930, teaching and assisting Douglas on a book on unemployment. Aaron was evidently a very effective teacher— the Nobel economist Paul Samuelson recalls that it was a course of Aaron’s that introduced him to economics when he was a college student here and that course first excited his interest in the subject.

The next few years after 1934 Aaron was a migrant worker of a different sort: 2 years in Washington at the US Treasury Department, then back to Chicago to work with Jacob Viner, then in 1937 a year at the London School of Economics researching for a dissertation that was planned to be on the Bank of England but never finished, then back to Chicago, then off to Washington, this time to work successively in the War Department, the Alien Properties Bureau, and the Commerce Department on International Trade.

And then in 1946, he was back to Chicago, to teach in the law school, an appointment he owed to the high opinions of him held by Henry Simons and Friedrich Hayek.

Over this period, Aaron maintained his silence in publication, at least under his own name. But he told me a story about how he had once written a syndicated column for Scripps-Howard that appeared in such papers as the New York World Telegram in the early 1940s. It was published on the opinion page, immediately beneath the column of Westbrook Pegler and just above Eleanor Roosevelt’s daily diary, a column she called “My Day.” You would not discover this from reading the newspaper since Aaron’s name did not appear; the columns were attributed to General Hugh S. Johnson (“Old Ironpants”), the man who had run Roosevelt’s National Recovery Administration until it was canceled by the Supreme Court in 1935 as unconstitutional.

The story Aaron told me was that in 1942 he had become friends with Johnson’s son Kilbourne while working in Washington. In March and April, Hugh Johnson was taken by a serious bout of pneumonia and had trouble keeping up with his daily column, and the son asked Aaron to ghostwrite a few columns, and he did. Hugh Johnson died of pneumonia in the early morning of April 15, and the next issue of Time magazine carried a long obituary. In the course of the obituary, the writer remarked that there was no sense of imminence in Johnson’s last column, a column on taxes and prices that appeared the day of his death. And the writer quoted the opening sentence of the column. Yes, the column was one that Aaron had written; the opening sentence was pure Aaron: “There appears to be no end to the lack of frankness and coordination among high government officials.”

My father wrote several times of his great admiration and warm affection for Aaron, describing him as “a paragon of all collegial virtues,” and described his mind as a “probing intelligence that thinks its way to the bottom—or at least to an unfamiliar depth—of many questions.” Aaron always protested at statements that exceeded logical limits or available evidence, and in this last sentence I can see my father pausing after “thinks its way to the bottom” and, realizing that Aaron would not approve, adding “or at least to an unfamiliar depth.” Aaron was an extraordinary man, and we should be proud of his influential association with the University of Chicago.

Stephen Stigler is the Ernest DeWitt Burton Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago, Department of Statistics. This article is based on a talk given on February 2, 2005, at the University of Chicago Law School and was originally published in the Journal of Law and Economics, vol. XLVIII (October 2005) © 2005 by The University of Chicago.

The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.