Has Mexico imported its obesity epidemic from the United States? A new study suggests that the answer to this question is “yes.”

The obesity epidemic has reached the Global South. Today, the region hosts some estimated 62 percent of obese individuals in the world (Ng et al., 2014). Developing countries have seen a threefold surge in overweight rates over the period 1980 to 2008 (Keats and Wiggins, 2014). Over the same period, emerging economies have become increasingly exposed to international trade in foods.

Are globalization and international trade the culprits to blame for the astonishing obesity trends? Many policy makers and the media seem to think so. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2015) for one has been advocating to integrate health concerns into trade policies. In the much discussed case of Mexico, the New York Times (Dec. 11, 2017) stated that “few predicted when Mexico joined the free-trade deal that it would transform the country in a way that would saddle millions with diet-related illnesses.”

Policymakers in the Global South are rightly worried: Obesity is costly—both economically and health-wise (Cawley, 2015). Their countries are currently facing a “nutrition transition,” during which diets gravitate towards processed foods, animal fats and sugars as income levels rise. And some countries’ health systems are likely to suffer from a double disease burden, at least in the medium term, as they are still grappling with traditional health problems including undernutrition.

The obvious policy question is: How can countries effectively manage this transition while still benefiting from the perks of globalization? In our recent research on Mexico, we show how the country has imported (at least in part) its obesity epidemic from the United States.

Has Mexico Imported Obesity From the United States?

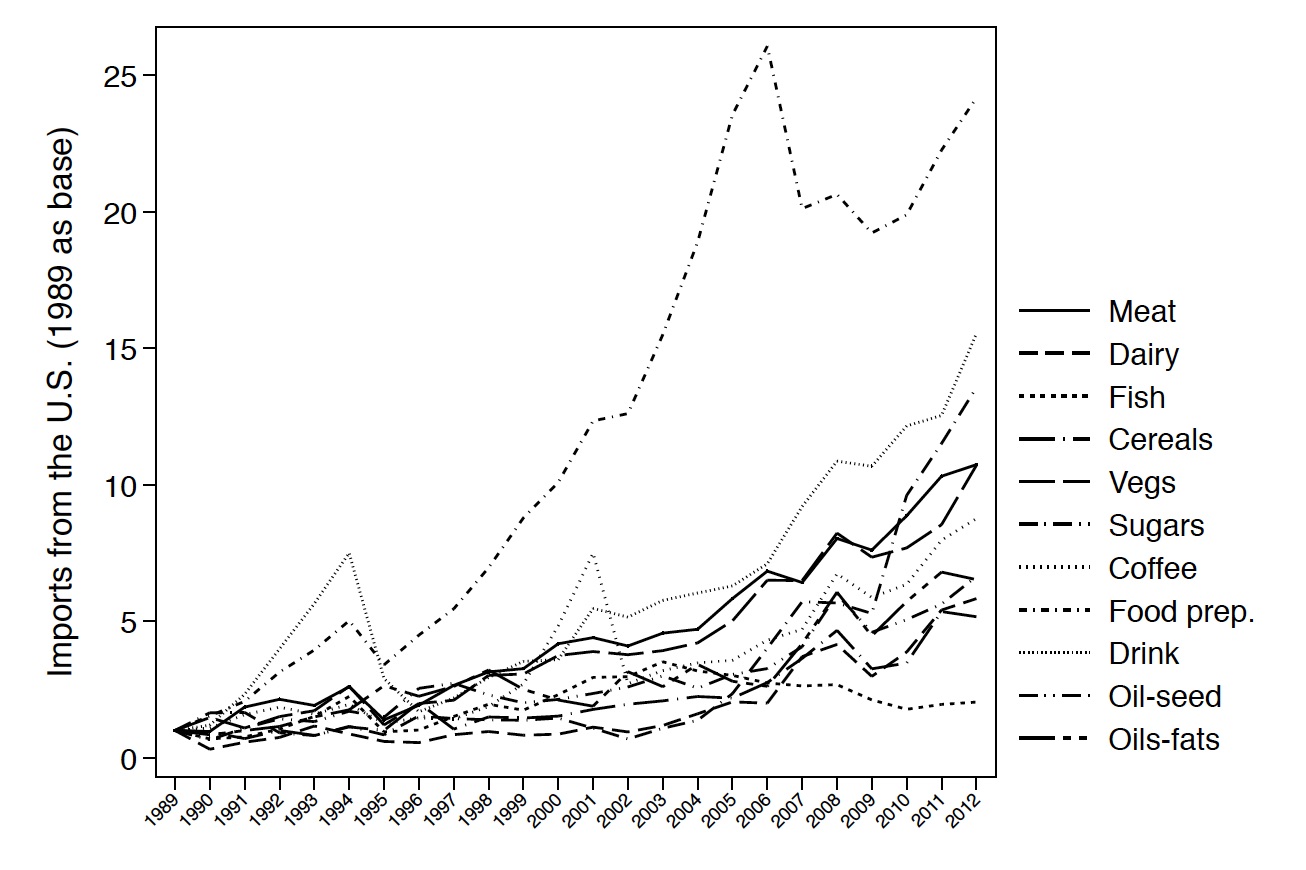

Mexico’s obesity rate grew from 10 percent to 35 percent over the period 1980–2012 (according to our analysis sample including adult females). The country is now among the “heavy weights” in the OECD, second only to the United States when it comes to obesity rates (OECD, 2017). As diets and population health were in flux, so was trade; over the very same period, Mexico engaged in intense economic integration with the United States, including the creation of NAFTA. Today some 80 percent of Mexican food imports arrive from its northern neighbor. In figure 1, we illustrate Mexican imports of Foods & Beverages from the United States over time. While overall food imports have risen, the “unhealthy” type has done remarkably so. Notably, exports of “food preparations” are 23 times bigger in 2012 than in 1989.

Figure 2 depicts Mexican food imports from the United States falling into unhealthy and healthy categories based on the USDA Dietary Guidelines. While Mexico has also imported healthy foods (such as dark green veggies), food imports have been increasingly concentrated in unhealthy ones (think sugar-sweetened beverages).

These trends invite a natural question: Is there a causal link between increased trade integration in food markets and surging obesity rates (Rogoff, 2017)? Or is this a purely spurious association? Our recent study suggests the former: Trade integration (in foods) has accelerated the country’s nutrition transition.

Estimating Weight Gains From Trade in Foods

In our recent working paper (Giuntella, Rieger and Rotunno, 2018), we study the impact of US food exports on obesity rates across Mexican states from 1988 to 2012. Our study combines several rounds of anthropometric and household expenditure surveys with product level food trade data. We focus on Mexican women, as data for men are only available in later years.

Trade integration is a national or aggregate shock. However, we exploit the fact that not all regions are impacted in the same way (see Dix-Carneiro and Kovak, 2017; Atkin and Donaldson, 2015; and Autor et al., 2013). To quantify the effect of US food exports at the sub-national level, we distribute aggregate food imports to Mexican states based on their historical consumption patterns. More specifically, we ‘impute’ each state’s exposure to trade in foods with its expenditure by food products prior to trade integration. Intuitively speaking, Mexican states that historically consumed a lot of processed foods will also be more exposed to imported processed foods from the United States.

In fact, we find large differences in food expenditure patterns across regions, which lends credibility to our empirical approach. We also control for a series of economic risk factors linked to obesity (such as food prices, GDP, FDI, and migration), as well as temporal trends and state characteristics (such as distance to the US border).

One concern for our analysis is that third factors such as aggregate demand (for American foods) drive both ‘imputed’ food imports by Mexican state and obesity prevalence. This, in turn, can lead us to estimate a spurious rather than a causal link. To net out demand effects and focus on supply-side shocks, we rely on “gravity residuals” (see also Autor et al., 2013). These are estimates of supply-side components of US food exports to Mexico (for instance, US comparative advantage relative to Mexico in third markets).

Quantifying Weight Gains From Trade in Foods

Our empirical results suggest that 422,000 Mexican women turned obese due to trade with the United States from 1988 to 2012. This striking effect is comparable to the one associated with exposure to Walmart supercenter expansions in the United States (see study by Courtemanche and Carden, 2011).

The impact of American food imports on obesity is large compared to those associated with food imports from other countries and total food expenditures of households. In other words, American foods seem more prone to lead to obesity. This pattern is confirmed when we differentiate between healthy and unhealthy components of total trade in foods. Our estimates suggest that it is the latter which drives our overall effects.

Health Inequality and Trade

What we call “weight gains from trade in foods” also varies across socio-economic groups. The unhealthy impacts of food imports are relatively larger among women with no or little education. If one takes a woman with at least a high school degree, her risk of obesity increases by 5 percent as exposure to American food imports moves from zero to the Mexican average. In comparison, a woman with no education faces an increased risk of 8 percent. This amounts to a 3 percent difference in the risk of obesity (see figure 3).

Policy Implications

Economists agree that countries gain from international trade; their consumers may for instance benefit from lower prices, new products or varieties. Here, we present evidence of a perhaps unexpected and likely unwanted gain—a gain in body weight. Our paper complements growing evidence on the adverse health effects of trade, which however has exclusively focused on the health of workers but less so on consumers—see for instance Colantone et al. (2017); McManus and Schaur (2016; and Pierce and Schott (2016).

That said, trade in foods has not triggered but merely accelerated Mexico’s ongoing nutrition transition. Our findings may inform policy makers elsewhere in the Global South as they are opening their markets to food imports from the rest of the world. Countries in the north typically hold a comparative advantage in unhealthy, processed foods. So when liberalizing trade in foods, it may be wise to incentivize healthful imports. Otherwise, trade integration may fuel the nutrition transition, increasing the possibility and length of a double burden of disease.

Osea Giuntella is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the Department of Economics of the University of Pittsburgh. His areas of interest are health, labor and economic demography. He is also a Research Fellow at IZA and at the Global Labor Organization. He obtained his PhD in Economics at Boston University and was a post-doc at the Blavatnik School of Government (University of Oxford) and a Research Fellow at Nuffield College. He has published in journals such as the Journal of Health Economics, Health Economics, Demography, and the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization.

Matthias Rieger is an Assistant Professor, Development Economics at the International Institute of Social Studies, Erasmus University Rotterdam. His areas of interest are development, health and experimental economics. He is also on the management team of the Rotterdam Global Health Initiative. He completed his PhD in International Economics at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in 2013 and was a Max Weber Fellow at the European University Institute, Florence. He has published in journals such as the European Economic Review, Journal of Health Economics and Demography. E-mail: matthias.rieger@graduateinstitute.ch; Web: http://matthiasrieger.weebly.com.

Lorenzo Rotunno is an Assistant Professor in Economics at Aix-Marseille University. His research interests include international trade, development, and political economy. Previously he was Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at the Blavatnik School of Government and Nuffield College (University of Oxford). He holds a PhD in International Economics from the Geneva Graduate Institute. E-mail: lorenzo.rotunno@univ-amu.fr, Web: https://sites.google.com/site/rotunnoheid/

References

Atkin, D., 2013. Trade, tastes, and nutrition in India. American Economic Review 103(5),1629-1663.

Autor, D.H., Dorn, D., Hanson, G.H., 2013. The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States. American Economic Review 103(6), 2121-68.

Cawley, John. “An economy of scales: A selective review of obesity’s economic causes, consequences, and solutions.” Journal of health economics 43 (2015): 244-268.

Colantone, I., Crino, R., Ogliari, L., 2017. Import competition and mental distress: The hidden cost of globalization. Technical Report. mimeo.

Courtemanche, Charles, and Art Carden. “Supersizing supercenters? The impact of Walmart Supercenters on body mass index and obesity.” Journal of Urban Economics 69.2 (2011): 165-181.

Dix-Carneiro, R., Kovak, B.K., 2017. Trade Liberalization and Regional Dynamics. American Economic Review 107(10), 2908-46.

Giuntella, O., Rotunno, L., Rieger, M., 2018. Weight Gains from Trade in Foods: Evidence from Mexico, NBER Working Paper 24942. Available here.

Keats, S., and S. Wiggins. “Future diets: implications for agriculture and food prices-Report for Shockwatch: managing risk in an uncertain world.” London: Overseas Development Institute and UK Department of International Development (2014).

McManus, T.C., Schaur, G., 2016. The effects of import competition on worker health. Journal of International Economics 102, 160-172.

Ng, M., Fleming, T., Robinson, M., Thomson, B., Graetz, N., Margono, C., … & Abraham, J. P. (2014). Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The lancet, 384(9945), 766-781.

Pierce, J.R., Schott, P.K., 2016. Trade Liberalization and Mortality: Evidence from U.S. Counties. Technical Report 22849. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Rogoff, K., 2017. The US is Exporting Obesity. Project Syndicate, Dec 1, 2017. Available here.

Update, OECD Obesity. “Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2017.” (2017).

World Health Organization. “Trade, foreign policy, diplomacy and health.” Food Security. Retrieved from WHO website (2015).

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.