Until 2016, anonymous buyers could purchase US real estate in cash through shell companies without reporting their real identities. But that year a new Treasury Department regulation closed this loophole in key US housing markets—and sparked an enormous drop in these types of transactions. The result points to how important anonymous capital flows are for global money launderers.

Until recently, it was easy to buy US real estate anonymously. All-cash buyers could acquire properties through a shell company without reporting the identity of the true owners to any authorities or financial institutions. In 2001, the PATRIOT Act tightened money-laundering regulation in the US but it did not cover real estate. Heavy industry lobbying allegedly influenced the decision to exempt the real estate sector from the Act.

To illustrate the regulatory loophole in real estate, consider someone who would like to deposit $1 million in a US bank account. To do this, they have to open an account, prove their identity, and possibly explain the origin of the funds. The bank is required to file a Suspicious Activity Report if they have any suspicions regarding the transaction. However, if the same person were to incorporate a limited liability company as a “shell company” and use the $1 million to buy a house in the company’s name, they never become a bank customer and are not subject to any know-your-customer regulations. The funds are paid directly to the seller and only the shell company’s name appears in public property records.

Anonymized transactions such as these are a global problem as they can be used to launder money. Domestic buyers can, for example, use shell companies to launder illicit profits or repatriate undeclared offshore funds and foreign buyers can use them to hide wealth from their home country’s authorities. Shell company real estate purchases also provide a method for hiding proceeds from corruption.

In 2016, FinCEN (a bureau of the US Department of the Treasury) announced a shift in US policy toward these transactions and introduced Geographic Targeting Orders (GTOs), which require title insurance companies to identify the beneficial owners of shell companies in certain residential purchases. The first GTOs covered transactions of shell companies paying $1 million or more in cash for homes in Miami-Dade and $3 million or more for homes in New York City. Later in August 2016, additional GTOs were issued for a number of additional counties in California, Florida, New York, and Texas. The GTO policy targeted all-cash buyers, because mortgage buyers were already covered by existing know-your-customer and identification requirements, and these counties targeted by FinCEN were those with the greatest existing volume of all-cash purchases by corporations.

In our paper “Anonymous Capital Flows and US Housing Markets,” we analyze how this shift in anti-money laundering policy affected residential real estate purchases made by corporate all-cash buyers. Our study uses housing transaction data obtained from Zillow Corp. Crucially for our analysis, this dataset includes information on buyer type, which allows us to separate corporate buyers from other buyers. We can also separate mortgage buyers from all-cash buyers in a smaller sample covering 17 states and Washington, DC.

The shift in anti-money laundering policy provides an interesting experiment on anonymity. If corporate buyers use shell companies for reasons unrelated to anonymity from authorities, there should be no change in their purchase volume. On the other hand, if there is a reduction, its size reveals the volume of anonymity-seeking investors.

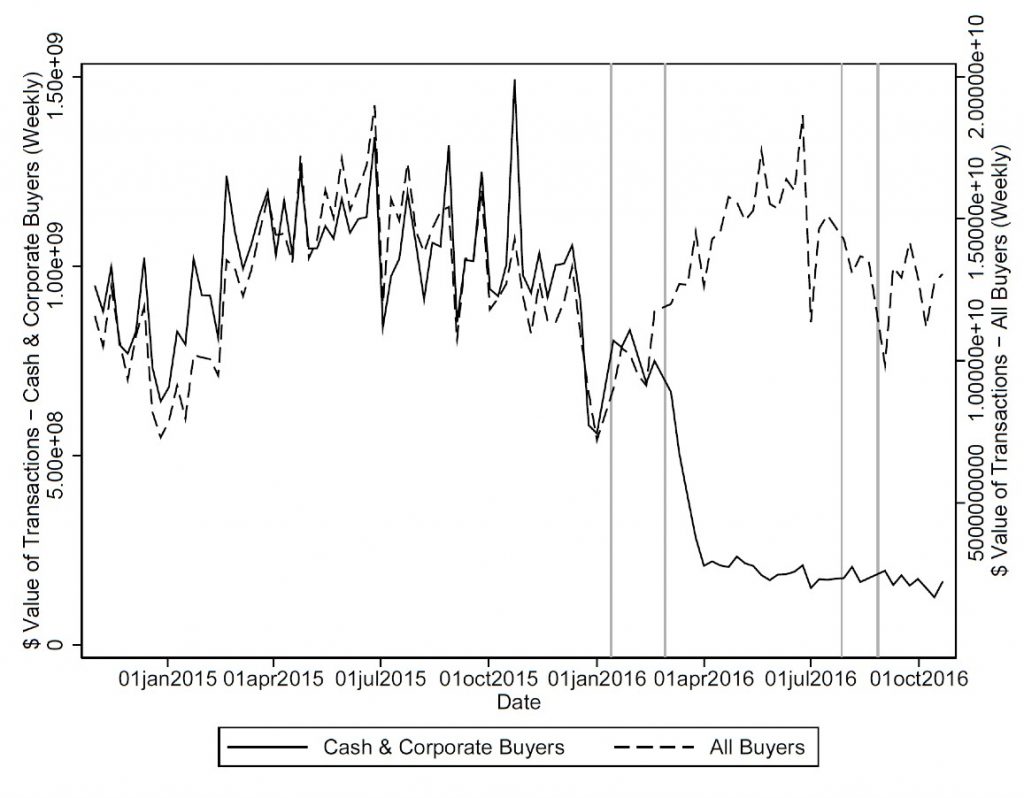

After the first FinCEN GTOs became effective in March 2016, we observe a dramatic decline in high-end real estate purchases by corporate all-cash buyers nationwide (see Figure 1). Based on a regression discontinuity design, we estimate that the weekly dollar volume of corporate cash purchases in our sample decreases by 66 percent. The annualized decrease in corporate purchases amounts to $45 billion, or approximately 7 percent of total house purchases (in dollars) in this sample.

Interestingly, we observe that after the first GTOs become effective, corporate cash purchases decline significantly across the board, both in the targeted counties and in areas not covered by the original regulation. We suspect that this aggregate nationwide shock is caused by fear of further regulation and FinCEN’s publicly announced focus on suspicious shell company real estate purchases. Further actions from authorities did follow the initial GTOs: shortly afterwards, FinCEN also made requests for Suspicious Activity Reports from real estate professionals, and in spring 2018 the range of transactions covered by the GTOs was expanded without announcing the change publicly.

We also observe a relative decline in high-end house prices in any county eventually targeted by a GTO after adjusting for national price development. Measuring changes in high-end real estate prices is not straightforward, but using Zillow’s price index data, we estimate that prices in the top third of the market in the GTO counties grew 4 to 5 percent less than expected during the year following the change in FinCEN policy. The price effect suggests that assets that can be purchased anonymously may carry a price premium.

The magnitude of the change we observe indicates that US housing markets attract significant anonymity-seeking capital flows. These flows can potentially even contribute to errors in international net wealth statistics. Previous academic studies show that out-of-town buyers have local market and welfare implications. Additional demand may benefit a local economy through real estate dollars and property taxes, but at the same time, housing may become less affordable to local residents.

| Anti-money laundering enforcement relies largely on banks’ ability to flag suspicious transactions, but there are many expensive assets that can be purchased while avoiding know-your-customer regulations. |

We test for circumvention of GTOs and find no clear evidence that the intent of the policy was circumvented through purchases using trusts (which were not covered by GTOs), avoiding the use of title insurance, buying multiple lower-priced properties, or switching purchases to immediately neighboring counties (such as West Palm Beach if you could no longer buy anonymously in Miami-Dade). We do find that cash real estate purchases by non-corporate buyers increase after the GTOs, which could consist of would-be shell company buyers making purchases through other methods, or could simply be other buyers stepping in (or both). Interestingly, survey statistics of the National Association of Realtors indicate that foreign direct purchases of US residential real estate increased by over 50 percent during the 12 months after the change in FinCEN policy.

According to FinCEN’s announcement at the time, one motivation for the GTOs was to produce valuable data and inform broader efforts to identify money laundering risks in the real estate sector. Based on our findings, the GTOs are a big step in the right direction, but a federal law would be a better long-term solution, offering fewer potential loopholes.

More generally, the problem of anonymous capital flows is not only limited to real estate. Anti-money laundering enforcement relies largely on banks’ ability to flag suspicious transactions, but there are many expensive assets that can be purchased while avoiding know-your-customer regulations. For example, fine art, rare collector items, and expensive jewelry are often traded anonymously through shell companies, and anonymity is a core feature of cryptocurrencies.

A recent House Financial Services Committee bill proposal originally required that companies formed in the US disclose their real beneficial owners to FinCEN.((As of August 1, 2018, there has been a further development related to FinCEN regulation of anonymous corporate real estate purchases. Following a bipartisan effort, the Senate passed an amendment to a spending bill, asking the Treasury to study extending the beneficial ownership disclosure requirements of the GTOs nationwide. A Twitter message by Senator Marco Rubio mentions that the action was based significantly on recent reporting by the Miami Herald and he provides a link to an article that discusses our findings.)) But the beneficial ownership provision was removed from the final version. Our findings support the view that authorities should be able to identify the beneficial owners of shell companies. It is an issue currently being addressed globally and we hope it is addressed by the United States in the future.

Sean Hundtofte was, until recently, a Research Economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and is now the Chief Economist and Head of Credit Risk at Better Mortgage.

Ville Rantala is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the University of Miami Business School.

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.