Some 130 years before Friedman could begin arguing that a corporation’s sole responsibility was to make a profit for its shareholders, Boston’s Charles River Bridge Company had to convince the Supreme Court that corporations were private entities whose interests could diverge from the public interest. While it lost that case, the partial success of the Charles River Bridge Company’s reasoning with the court laid the foundations for corporate personhood as it exists today.

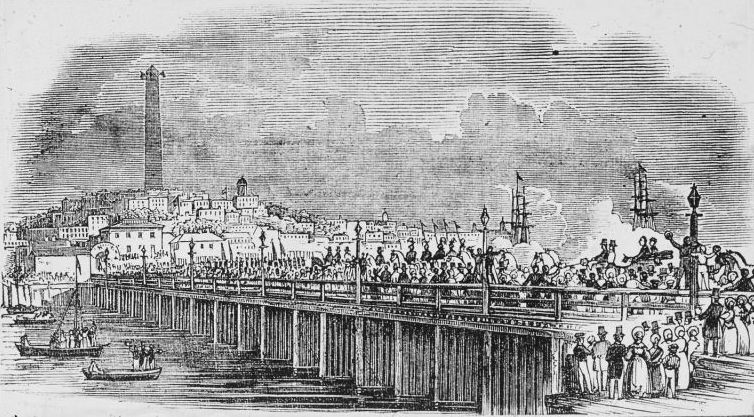

In 1837, two bridge companies sought to determine the constitutional rights of business corporations, and indeed the nature of the business corporation itself. The Massachusetts legislature had chartered a new, free bridge over the Charles River, which challenged the monopoly power of the corporation that owned the sole existing bridge. The proprietors of the old bridge, the Charles River Bridge Company, sued, claiming that they had a monopoly right to passage over the Charles River. They lost.

Historians have considered this controversy to be solely about the Supreme Court’s economic philosophy of market competition. The Supreme Court endorsed the chartering of the competing bridge, historians have said, because the new bridge challenged the monopoly power of the Charles River Bridge Company and promoted the expansion of commerce and enterprise. Yet, as I argue in my recent Stigler Center working paper, the case is about more than this: at its core, it is a contest over the nature of the business corporation itself. It pitted an older, traditional view of the corporation as a creature of the state, beholden to the public interest, against a newer vision of the corporation as a private, profit-making entity.

The “free bridge movement,” as it was called, was driven by the belief that corporations should be subject to popular control. This was particularly true of “internal improvement” (public works) corporations like bridges. When a corporation failed to serve the public’s “necessity and convenience,” supporters of the new bridge believed, the legislature had the right to take steps to remedy the situation by, for instance, chartering a competing corporation. Proponents of the new bridge accused the Charles River Bridge Company of accruing exorbitant profits on the backs of small farmers and merchants, who were forced to pay high tolls to cross their bridge in order to access the markets of Boston. The “people’s bridge,” as supporters called it, would challenge this monopoly by creating competition, and so promote increased access to the commercial metropolis that would boost the state’s economy.

In their lawsuit challenging the new bridge, the proprietors of the Charles River Bridge Company claimed that their corporation was a private entity whose sole purpose was to create profit for their shareholders. Any public benefit derived from their operation, they claimed, was “of no consequence.” Further, they argued, as a private entity, business corporations had constitutionally protected rights against the impairment of their contracts with the state—their charters—just as natural persons had. They claimed that their company’s charter possessed an implied right to a monopoly on traffic over the Charles River, which the state had “impaired” by chartering a competing corporation.

Yet in 1837, this vision of the corporation as a purely private, profit-maximizing entity was new. Rather, in the early years of the American republic, the corporation was considered to be a special grant by the state to a group of citizens, to allow them to pool their money to fund projects “of general utility,” such as bridges, roads, turnpikes, canals, and railroads. Supporters of the new bridge invoked this older vision of the corporation. The corporation, they argued, was a “creature of the state,” whose primary purpose was to promote the welfare of the community— here, by opening another avenue to Boston’s commercial center and thus encouraging economic development. Private profit-making, in this older view, was secondary. This was made clear in the new bridge’s charter, which mandated that once the new bridge’s shareholders recouped a 5 percent return on their investment, the bridge would revert to the city and become free. Investors were entitled to some profit, in order to encourage enterprise, but the primary purpose of the corporation was to serve the public. The Charles River Bridge Company directly challenged this older view.

|

By allowing internal improvement corporations to claim constitutional rights, the Court endorsed a vision of the corporation not as a servant of the public but as a private, rights-bearing entity whose interests were potentially opposed to those of the public. In other words, the welfare of the public was now pitted against the rights of the corporation. |

In the Charles River Bridge case, the Supreme Court confronted these competing visions of the corporation. Was the corporation a private, profit-making entity, or was it a creature of the state designed to serve the public interest? Chief Justice Roger Taney attempted to take a middle ground. The business corporation, he concluded, was a private entity with constitutionally protected rights, including the right to protection against impairment of its charter. However, Taney held, the Court would not read a charter to imply a grant of monopoly power, where no such a grant was explicitly made, because to do so was not in the public interest.

Although the Charles River Bridge Company lost the case, and indeed was forced out of business when the new bridge became free, Taney’s ruling ultimately proved a boon for corporations. The Supreme Court had adopted the Charles River Bridge Company’s argument that business corporations were private entities, not purely public creations. The Court also held that corporations possessed constitutionally protected rights on par with natural persons, with the caveat that these rights should be interpreted narrowly when they conflicted with the public interest. By allowing internal improvement corporations to claim constitutional rights, the Court endorsed a vision of the corporation not as a servant of the public but as a private, rights-bearing entity whose interests were potentially opposed to those of the public. In other words, the welfare of the public was now pitted against the rights of the corporation.

|

By granting corporations substantially the same rights as those the Constitution gives to individuals, the Supreme Court over the past two centuries has allowed corporations increasingly to shield themselves from state regulation, even when such regulation is arguably in the public interest. |

Granting business corporations the constitutional right of protection against impairment of contracts was also an important step in the development of corporate constitutional personhood. Since the Charles River Bridge case, business corporations have successfully claimed other constitutional rights enjoyed by natural persons, including the right to equal protection of the law, the right to protection against unreasonable search and seizure, and most recently, the rights to freedom of speech and religion. By granting corporations substantially the same rights as those the Constitution gives to individuals, the Supreme Court over the past two centuries has allowed corporations increasingly to shield themselves from state regulation, even when such regulation is arguably in the public interest.

Today, the view that business corporations are purely private entities with constitutional rights has largely won out. Recovering the history of this early conflict over the nature of the corporation, however, offers a valuable alternative vision of the purpose and responsibility of business corporations in modern society. The emergence of “benevolent corporations,” or “B-corps,” whose charters include the pursuit of particular public interest goals in addition to shareholder profit, evokes aspects of this older vision of the corporation. Although we are a far cry from labeling modern corporations like Google “the people’s search engine,” it bears considering how traditional views of business corporations might provide alternatives to a purely profit-driven model of the firm.