High-profile scandals like Odebrecht, The Panama Papers, and Swiss Leaks have brought down powerful politicians and businesspeople across Latin America. In Mexico, however, not a single person has been indicted, much less convicted, for wrongdoing in any of these cases.

International corruption scandals put local criminal justice and legal systems to the test. Even highly corrupt or ineffective national institutions are often forced to kick into gear when put under an international spotlight. In recent years, cases such as Odebrecht, The Panama Papers, and Swiss Leaks have led to numerous powerful politicians and corporate executives being swept up by the dragnet in countries like Peru, Brazil, Egypt, Ecuador, Panama, Uruguay, and the Dominican Republic.

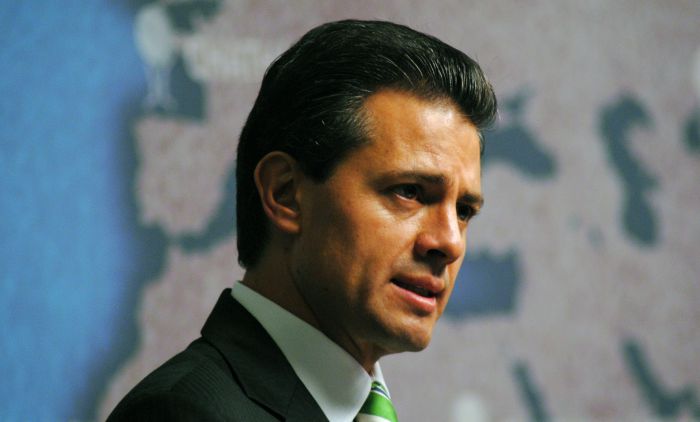

But in Mexico, impunity reigns supreme. Not a single person has been indicted, and much less convicted, for wrongdoing for any of these high-profile scandals. And when, a few days ago, one brave prosecutor tried to dig into the use of Odebrecht funds to finance president Enrique Peña Nieto’s 2012 electoral campaign, the prosecutor was summarily dismissed.

In Mexico, less than ten percent of all crimes are even reported to the authorities, according to official statistics. Of these, only two-thirds, or six percent of the total, are investigated. In general, the impunity rate stands at 99 percent. And when powerful individuals are involved, the numbers get very close to 100 percent.

Whenever an international corruption or tax-evasion scandal breaks out, Mexico is normally at the top of the list. Swiss Leaks unveiled the existence of enormous fortunes stashed in Swiss banks by some of the most powerful Mexican politicians and oligarchs, including Carlos Hank Rhon, Luis Téllez, and Alfredo Elías Ayub. The Panama Papers also directly implicated a series of top bureaucrats and contractors linked to the Peña Nieto administration, including Emilio Lozoya, Ricardo Salinas Pliego, Alfonso de Angoitia, and Juan Armando Hinojosa. And top officials of Odebrecht, and its partner Braskem, have given testimony in Brazil that suggests they funneled at least $10 million to top members of Peña Nieto’s team, both during the 2012 presidential campaign and in the context of negotiating oil refining contracts once Peña Nieto took power.

In general, Global Financial Integrity ranks Mexico as the third largest source of illicit financial flows in the world, after only China and Russia. Approximately $50 billion goes unaccounted for in Mexico each year due to money laundering operations, tax evasion, or other illicit transactions. But criminal convictions in this area are few and far between. Even “El Chapo,” Joaquín Guzmán Loera, has managed to keep his billion-dollar fortune out of reach of the authorities.

“The generalized suspicion is that Peña Nieto plans to use his last year in office to implement a vast cover-up operation in order to guarantee that none of his friends or associates, or he himself, could be brought to court by the next administration.” |

It is true that a series of state governors with close ties to Peña Nieto have recently been indicted or detained on charges of embezzlement and money laundering, including the infamous governor of Veracruz, Javier Duarte, and the former governors of Tamaulipas, Eugenio Hernández and Tomás Yarrington, of Chihuahua, César Duarte, and of Coahuila, Humberto Moreira.

Nevertheless, none of these powerful politicians has actually been convicted of anything. Their highly publicized detentions appear to have been more media theater than an actual effort to put the house in order. Indeed, the generalized suspicion is that Peña Nieto plans to use his last year in office to implement a vast cover-up operation in order to guarantee that none of his friends or associates, or he himself, could be brought to court by the next, possibly unfriendly, administration that will take the helm in December of 2018.

The clearest indication of the fact that Peña Nieto does not have any real interest in defending the rule of law during his last months in office is the sorry state of the federal prosecutor´s office (Procuraduría General de la República, PGR). The institution today stands leaderless, without its chief prosecutor, who resigned on October 16, and also with vacancies in the offices of both the special anticorruption prosecutor and the prosecutor for electoral crimes.

Peña Nieto has refused to propose to Congress any new names to occupy these crucial posts. The President has even stated publicly that he prefers to wait until after next year’s presidential elections before making any proposals. In addition, the law for the creation of a new autonomous national prosecutor’s office (Fiscalía General de la Nación), which would replace the PGR and be fully independent from the executive, has been held up in Congress due to obstructionism by Peña Nieto’s own Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

In the past, Peña Nieto was able to use the attention generated in the international financial press by his economic reform agenda to protect his government from international scrutiny of the continuous waves of corruption scandals and human rights violations that have rocked his government. But it appears that this clever game may now be coming to an end.

Even the most rapacious global corporations and international investment firms put a high premium on the rule of law. And it is becoming increasingly clear that the Mexican government simply does not comply with the most basic standards of institutional strength and government integrity.

The good news is that the Mexican people have also begun to open their eyes. Approval ratings for Peña Nieto and the PRI have reached historically low levels, mostly due to the government’s failure to establish effective rule of law.

Corruption will be the number-one issue on the agenda during the upcoming presidential elections, which will take place on July 1, 2018. And the polls indicate that voters will likely turn to the only candidate who has a credible record on this issue: Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

Such a result might give international investors temporary jitters, given López Obrador’s left-wing political convictions. But the maverick politician has been very clear that if he is elected he is committed to establishing a respectful relationship with the United States and that the top priority of his government will be honest government and the rule of law.

He has also been very clear that he will not act rashly in the economic realm. Although he will review oil and other public contracts to assure that they comply with legal standards, he has not spoken of nationalizations and he has openly ruled out “authoritarian action” in this and other areas of the economy. “The anchor for confidence is going to be the rule of law”, he stated in a recent interview with Bloomberg.

If López Obrador successfully fulfills his promises to strengthen public institutions, it would create an enormous sea change in Mexican politics whose rising tide would lift all ships.

John M. Ackerman is a Professor at the Institute for Legal Research of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), Editor-in-Chief of The Mexican Law Review and a columnist at Proceso magazine and La Jornada newspaper. Contact: www.johnackerman.blogspot.com Twitter: @JohnMAckerman

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.