The excesses of IP law are now a serious obstacle to innovation and economic growth.

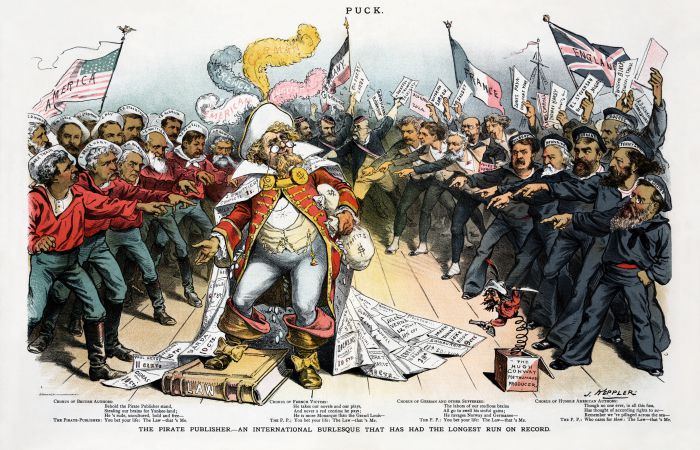

In the rogues’ gallery of regulatory rent-seeking, copyright and patent laws are the wolves in sheep’s clothing. According to the ingenious and highly effective rhetoric of their beneficiaries and supporters, these laws are the very antithesis of rent-seeking. Far from conferring special and undeserved privileges, they merely defend the rightful owners of “intellectual property” from “theft” and “piracy.” While rent-seeking misallocates resources and retards growth, intellectual property advocates claim that patent and copyright protections unleash artistic creativity and technological innovation by securing for artists and inventors just recompense for their efforts. Copyright and patent laws, therefore, are not only an integral part of the private property system that undergirds all market economies, but they are also a vital linchpin of innovation and growth in the contemporary knowledge-based economy.

Just as their supporters claim, intellectual property protection does deliver real benefits. By preventing others from copying their work, at least temporarily, IP protection boosts the payoff for artists and inventors and thus gives them stronger incentives to create and innovate. The problem is that IP protection also imposes costs, not just on consumers who have to pay higher prices for copyrighted and patented goods, but also on other artists and innovators. Unfortunately, a radical and ill-considered expansion in the scope and reach of this protection over the past few decades has resulted in a dramatic escalation of those costs with little in the way of compensating benefits. As a result, the rents that now accrue to movie studios, record companies, software producers, pharmaceutical firms, and other IP holders amount to a significant drag on innovation and growth, the very opposite of IP law’s stated purpose.

Until the 1970s, intellectual property was a sleepy little backwater of American law. The benefits of IP protection may have been modest, but so were the costs. Since then, the scale and complexity of IP law have exploded even as, with the rise of the information economy, the relative importance of IP-intensive industries has soared. Since 1976, copyright protection has been extended to unpublished works, the requirement to register one’s copyright has been dropped, and copyright terms have grown from 28 years (plus one possible 28-year renewal) to the life of the author plus 70 years. Enforcement of copyright law has also grown more aggressive: it is now done increasingly through criminal prosecution by the federal government rather than private civil complaints, and criminal fines have soared from $1,000 to $250,000 per infringement.

With regard to patents, the expansion of the law during recent decades has occurred largely through court decisions rather than via new legislation. In 1982, the newly established Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) was vested with exclusive appellate jurisdiction over patent cases. Since then, the CAFC has reshaped the law by lowering the standards for patentability and expanding the scope of patentable inventions to include software, business methods, and even parts of the human genome. As a result, the number of patents issued annually by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has increased almost fivefold, from 61,620 in 1983 to 109,414 10 years later, to 186,591 another decade later, to 302,150 in 2013.

The excesses of IP law are now a serious obstacle to innovation and economic growth. Hostility to unauthorized copying in virtually any form, the core principle of modern copyright law, stands in direct opposition to the logic of the Internet, the greatest technology ever devised for reproducing and disseminating information. Consequently, copyright law casts a pall over the most promising arena for technological and economic progress in the current age. Consider the Google Books Library Project, in which the Internet search giant is collaborating with major research libraries to digitize all the world’s approximately 130 million books (it has completed about 30 million so far). For books in the public domain, Google Books functions as an online library, with full texts available for reading and downloading. Alas, such books comprise only about 20 percent of the total. For all the rest, including the roughly 70 percent of all books that are out of print but still under copyright, Google Books can offer only brief snippets of text in response to searches—and its right to do that has been vindicated only after a decade of court battles with authors and publishers.

Similar problems afflict efforts to digitize and make publicly available the vast troves of recorded music, film, video, photographs, and artwork currently moldering in library archives. Between automatic copyright protection without formalities and greatly extended copyright terms, vast numbers of “orphan works” now exist whose copyright holders are unknown and unreachable. These works can’t be safely reproduced and disseminated because nobody knows whose permission to get first. Meanwhile, access to the vast storehouses of scientific research is bottled up by copyright. A small group of academic publishers, most prominently, Elsevier, Springer, and Wiley, rake in profit margins in excess of 35 percent as subscription prices for university libraries race well ahead of inflation. “Their business model [i]s a marvel,” writes copyright historian Peter Baldwin: “Sell scholarship back to the same universities whose scientists had produced, written, peer reviewed, and edited it largely for free.”

Meanwhile, the evidence is mounting that the patenting explosion has been harmful for many innovators. Research by James Bessen and Michael Meurer compared the estimated value of public companies’ patent portfolios to the estimated cost of defending patent cases during the 1980s and 1990s. In particular, they divided the public companies they studied into two groups: chemical and pharmaceutical firms, on the one hand, and all other firms, on the other. For both groups, the cost of defending patent cases began rising sharply in the mid-1990s. For chemical and pharmaceutical firms, the value of their patent holdings remained clearly greater than those litigation costs, approximately $12 billion in value compared with roughly $4 billion in costs as of 1999. For all other industries, however, the situation was reversed. By 1999, litigation costs had soared to around $12 billion, whereas the total value of their patent holdings was only $3 billion. In other words, outside the chemical and pharmaceutical industries, American public companies would apparently be better off if the patent system didn’t exist.

A major part of the problem lies in the differences between chemical and pharmaceutical patents and most other kinds of patents. For the former group, the scope of patents is clearly and precisely delineated by chemical formulas. Accordingly, it is relatively straightforward for subsequent innovators to discover whether their new products are covered by any existing patents. By contrast, the scope of other kinds of patents, especially new-style patents for software or business methods, is described by abstract language that is invariably open to differing interpretations. This vagueness in the boundaries of intellectual property, combined with the immense number of patents in force at any one time, make it virtually impossible for downstream innovators to be sure whether the new products they are developing are infringing on someone else’s patents.

The dysfunctions of the patent system have been exacerbated in recent years by the rise of so-called patent assertion entities, better known as “patent trolls.” Patent trolls are firms that neither manufacture nor sell products but instead specialize in amassing patent portfolios for the purpose of initiating infringement lawsuits. According to a White House report, lawsuits by patent trolls tripled between 2010 and 2012 alone, as the share of total patent infringement suits initiated by such firms rose from 29 percent to 62 percent. That’s right: most patent infringement suits are now brought by firms that make no products at all and whose chief activity is to prevent other companies from making products. A 2012 study found that the direct costs of defending patent troll suits (i.e., lawyers’ and licensing fees) came to $29 billion in 2011. To put that figure in context, it amounts to more than 10 percent of total annual R&D expenditures by U.S. businesses.

The current state of intellectual property law may be bad for economic growth overall, but it is highly effective at showering riches on a favored few. In IP-intensive industries, the monopoly power created by copyright and patent protections encourages industry concentration, inflates corporate profits, and exaggerates the tendency toward winner-take-all “superstar markets.” As a result, income and wealth are even more highly concentrated at the top than would otherwise be the case.

The IP-intensive industries of entertainment, software, and pharmaceuticals all feature powerful economies of scale. The upfront fixed costs of producing the first copy of a product are high, while the variable costs of producing additional copies are low. The larger the sales volume, the more sales there are over which fixed costs can be spread and for which the unit costs of production will be lower. This dynamic leads to high levels of concentration in which a few firms account for the vast bulk of sales and profits.

Pushing in the other direction, however, is the vulnerability of companies in these industries to relatively easy imitation. Open competition would allow new entrants that did not have to incur all the heavy fixed costs of the first mover and that could therefore sell profitably at a much lower price. These new entrants would drive down prices and take market share away from the first mover (although significant first-mover advantages still remain).

Strong intellectual property protection—copyright for entertainment, patents for drugs, and a combination for software—eliminates or at least reduces this threat of copycat competition. Accordingly, the effect of patents and copyright is to allow industry leaders to take fuller advantage of the potential scale economies that the nature of their industries permits. The result is even higher levels of inter-firm inequality than would otherwise be possible, with industries dominated by a few highly profitable giants.

Consider how top-heavy the entertainment industry has become: three record labels (Universal Music Group, Sony Music, Warner Music Group) account for roughly 85 percent of U.S. recorded music sales and 70 percent of the global market, while five movie studios (Walt Disney, Sony, Twentieth Century Fox, Universal Pictures, and Warner Brothers) have captured around 70 percent of the U.S. market and 50 percent globally. The computer/software industry has featured a succession of dominating giants, with Microsoft, Apple, Google, Facebook, and Amazon topping the list. Concentration in the pharmaceutical sector has been checked to some extent by the rise of generic drug producers and biotech startups, but still a merger wave in recent decades has produced the huge companies now known as “Big Pharma.” As a result, the market share of the top ten firms in the industry jumped from around 20 percent of global sales in 1985 to 48 percent by 2002. The profitability of the sector is abnormally high, with average operating margins around 25 percent, compared to 15 percent or less for other consumer goods producers.

The enormous aggregations of market capitalization and profits in the IP-intensive industries then translate into soaring wealth and incomes for shareholders, employees, and professionals. Most obvious are the vast fortunes made in entertainment and the Internet sector, but the effect on economic inequality is considerably broader than the mind-boggling payouts for those at the very top of the income scale. Because these industries are skill intensive (i.e., their employees are more highly skilled than the work force as a whole), any pass-through of rents to workers in the form of higher wages will go mainly to more highly educated and highly paid employees. The effect then is to further increase the growing inequality between the highly skilled and everybody else.

The copyright and patent laws we have today therefore look more like intellectual monopoly than intellectual property. They do not simply give people their rightful due; on the contrary, they lavish special privileges on copyright and patent holders to the detriment of everyone else. Therefore, it is entirely appropriate to strip IP protection of its sheep’s clothing and to see it for the wolf it is, a major source of economic stagnation and a tool for unjust enrichment.

[Brink Lindsey (@lindsey_brink) is vice president and director of the Open Society Project at the Niskanen Center. Steven M. Teles is associate professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University and a senior fellow at the Niskanen Center. This piece is adapted from their upcoming book “The Captured Economy: How the Powerful Enrich Themselves, Slow Down Growth, and Increase Inequality” (Oxford University Press).]

(Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the names of the major U.S. labels and movie studios)

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.