Should the U.S. enforce more explicit restrictions on monopolies, or can innovation and democracy alone mitigate the pervasive effects of monopoly power? A panel of historians and economists at the recent Stigler Center conference on concentration in America discussed the historical evolution of this debate.

In 1776, just as the United States was making its Declaration of Independence, Adam Smith published his magnum opus The Wealth of Nations. While Smith famously described the “invisible hand” of the free market, he also emphasized the “wretched spirit of monopolies.”

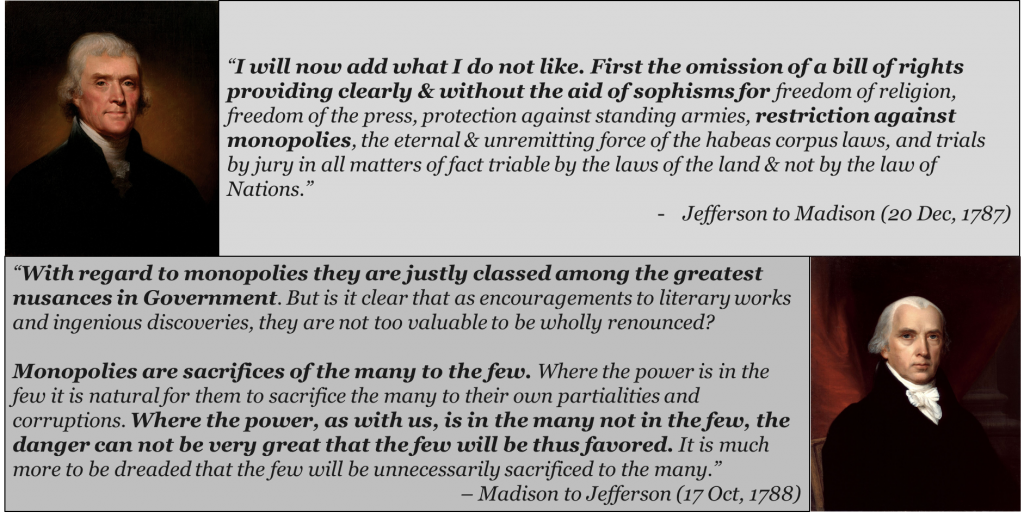

The founders of the United States considered monopolies to be detrimental to freedom. Thomas Jefferson wrote to James Madison from Paris in 1787, giving his thoughts on the proposed Constitution. He wrote that he did not like the omission of a “restriction against monopolies” from the Bill of Rights. Jefferson wasn’t alone in his concerns. In a reply to Jefferson in 1788, Madison also called monopolies “among the greatest nuisances in Government.” Yet he hoped that with “encouragements to literary works and ingenious discoveries” and democracy (“where the power… is in the many, not in the few”) their “danger can not be very great.”

The correspondence between Jefferson and Madison encapsulates the long public debate on monopoly and regulation, where those like Jefferson desire more explicit restrictions on monopolies, while those like Madison hope that innovation and democracy will mitigate its pervasive effects. At the recent Stigler Center conference on concentration in America, a panel of historians and economists, moderated by leading antitrust lawyer Gary Reback, discussed the evolution of this debate.

Antitrust and the Chicago School(s)

Chicago Booth economist and Director Emeritus of the Stigler Center Sam Peltzman discussed the evolution of two Chicago Schools, the Hawkish and the Dovish, that engaged in a similar debate. The Hawkish Chicago School, led by economist Henry Simons during the Great Depression and the Second World War, would fit closer to the views of Thomas Jefferson.

Simons emphasized the centrality of competition and a zealous maintenance of competition with vigorous enforcement of antitrust laws. In this view, markets should have a large number of firms with low market concentration. This hawkish view remained dominant in the 1950s and 1960s and culminated in the Neal Report of 1968, which recommended “a clear mandate to use established techniques of divestiture to reduce concentration in industries where monopoly power is shared by a few very large firms.”

In contrast, the Dovish Chicago School, led by legal scholar Aaron Director in the 1950s, was more cautious in calling all forms of concentration detrimental, and emphasized a “rule of reason” to consider whether such concentration was efficient and welfare enhancing.

This view found its most popular expression in the 1978 book The Antitrust Paradox by Director’s student Robert Bork, a Yale legal scholar and possibly the most influential antitrust scholar of the last 40 years. The book argued that protecting inefficient and uncompetitive small businesses in pursuit of antimonopoly might actually hurt customer welfare.

“The view (of the dovish Chicago School) is unless concentration is sufficiently high, competition is going to be a dominant strategy,” said Peltzman. This school, which represents the predominant view on antitrust today, thus raised the question of whether some monopolies could be welfare enhancing and efficient.

Antitrust and the 1890 Sherman Act

Business historian Richard John of Columbia University provided an authoritative brief of the rich history of the debate on antitrust in the United States, saying that “Antimonopoly is as old as the republic.”

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the landmark law in U.S. antitrust, has been historically misunderstood, in his view, and there is a deep tradition of antimonopoly in the United States. Founding figures like Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and John Adams frequently wrote about monopoly in the late eighteenth century, and antimonopoly laws like the New York Banking Act of 1838, the New York Telegraph Act of 1848, and the National Telegraph Act of 1866, which regulated monopolies like Western Union, were some of the laws that were legislated before the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. John reminded that Senator John Sherman, after whom the famous Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 is named, was largely responsible for the enactment of the Telegraph Act of 1866.

John noted that the Sherman Antitrust Act lacked the bite of enforcement, and it was not until the 1910s that antitrust laws began to vigorously get enforced, with actions like the break-up of Standard Oil and the American Tobacco Company in 1911. He also argued that the motivations behind the antitrust law did not lie in consumer welfare, and it was largely meant to protect the “interests of small dealers and worthy men” (Justice Rufus Peckham, 1897).

On the politics behind the passing of the Sherman Act, John noted: “Historians have long observed that the Act is best understood not by itself but as part of a grand legislative bargain that included a major tariff increase.” He added: “Most of the Republicans who backed the law—both the House and the Senate had Republican majorities at the time—favored high tariffs, which critics derided, not implausibly, as not only anticompetitive but anti-consumerist.”

John showed that the intellectual history of antimonopoly was as old as the inception of the United States, and such historical context is necessary to understand the evolution of antitrust thought.

Antitrust and Louis Brandeis

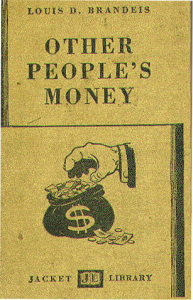

University of Oregon political scientist Gerald Berk discussed the influence of Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, a leading legal figure in the early twentieth century on antitrust who fought railroad monopolies. Berk emphasized how Brandeis was both a proponent of scientific management, emphasizing efficiency in organizations, and a leading advocate of antitrust.

Brandeis didn’t view efficiency and antitrust as antithetical to each other, unlike some modern legal scholars like Robert Bork. Brandeis believed that the role of antitrust was to undermine concentration of power that might undermine civic responsibility.

Discussing the views of Brandeis on competition, Berk said: “Competition (for Brandeis) is neither God or devil… Competition for Brandeis can just as easily turn predatory as it can turn towards improvements in products and production processes. For Brandeis, the policy question, which is simultaneously a political and economic question, is how do you distinguish predatory from productive competition?”

Thus, Brandeis’ ideas attempted to find balance between efficiency, competition, antitrust, and civic responsibility and led to a distinct approach of dealing with antitrust: “regulated competition,” where “the government steered economic development away from concentrated power by channelling competition from predation to improvements in products and production processes.”((Berk, 2011))

Antitrust and Intellectual Property

Harvard economist and innovation scholar F.M. Scherer discussed the history of intellectual property in the United States in the context of America’s broader history of antitrust.

The United States held a mercantilist policy on intellectual property in the nineteenth century, in which foreigners weren’t allowed to hold patents until 1836. Even later, the fee structure of applying for patents favored locals, as fees for foreigners were detrimentally expensive.

Just as antitrust enforcement was lax until the 1920s, before the influence of figures like Brandeis, Scherer pointed out that until the 1930s United States had a policy of “benign neglect” regarding abuse of patent laws. He showed that the period from the 1930s until the 1970s saw tougher enforcement of patenting laws on firms like AT&T, IBM, and Xerox.

Scherer cited extensive research that shows how such tough enforcement regimes like use of compulsory patent licensing didn’t have detrimental effects on innovation. “In a statistical analysis, we showed that the guys who were subjected to compulsory licensing, all else equal, had actually raised their R&D efforts relative to their peers,” he said, adding that “In the ‘Economic Impact of the Patent System’ in 1973, Aubrey Silberston and C.T. Taylor found a system of widespread compulsory licensing of patents would reduce R&D expenditures by maybe 10 percent. Ed Mansfield in 1986, probably the leading scholar on the economics of technological innovation, found mixed effects.”

Concurrent with the rise of the Dovish Chicago School, Scherer pointed out that since the 1970s there has been a return of a more benign regime of enforcement of patenting laws that was motivated by concerns regarding decline in U.S. innovation, which in his view were not backed by evidence.

Scherer shared an 1889 cartoon on antitrust, which appeared in Puck Magazine, that reflected the antimonopoly sentiment at the time, just before the passing of the Sherman Act.

In the cartoon, the “People’s entrance” to the Senate is bolted and barred, while there is a special “Entrance for Monopolists” and the Senate operates under the motto: “This is the Senate of the Monopolists by the Monopolists and for the Monopolists!”

Reback asked the panel what factors may have influenced the public conversation around antitrust. John stated how magazines like Puck were similar to the late night comedy shows of today and that political satire can help in advancing the conversation on such issues.

The rich intellectual history of antitrust discussed at the panel showed how the debate around antitrust remains a core and nuanced debate, just as it was at the end of the eighteenth century between Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Adam Smith. Several questions remain unresolved:

-

Can market concentration be efficient? If so, when—and who gets to adjudicate this question?

-

Should we put more power in the hands of hawkish governments, as Jefferson desired? Or should we, like James Madison, trust democracy to rein in monopolies? What are the effects of monopolies on democracy and civic responsibility itself? Should “efficient” monopolies be acceptable even if their concentrated power could influence democracy and civic engagement itself?

-

Should monopoly regulation be driven by clearly coded guidelines? Does such codification like the Sherman Act actually work? Or, should it be open to the interpretation of legal figures like Louis Brandeis and Robert Bork?

While the answers to these questions and more are not easy, engaging in this debate in a historically aware manner is critical.