Media scholar Jonathan Taplin, author of the new book Move Fast and Break Things, on the rent-seeking and regulatory capture of digital platforms.

In 2014, Silicon Valley venture capitalist Peter Thiel famously proclaimed that “competition is for losers” in an essay published in the Wall Street Journal and in his book (also published in 2014) Zero to One. “If you want to create and capture lasting value, look to build a monopoly,” he advised entrepreneurs, expounding on his view that monopolies are good for innovation and, ultimately, for society at large.

Thiel’s proclamation has received a lot of attention since he made it, not just because it seemingly goes against the very notion of a competitive capitalism, but also because in the eyes of many, it perfectly captured the underlying philosophy behind the rise of digital platforms like Google, Facebook (whom Thiel was the first outside investor in), and Amazon.

In terms of market share and profit margins, the big digital platforms, particularly Google and Facebook, enjoy an astounding level of dominance. Google, in effect the world’s largest media company, has an 88 percent market share in search advertising. Facebook (including Instagram, Messenger, and WhatsApp) controls over 70 percent of social media on mobile devices. Together, the two firms received 85 cents of every new dollar spent in online advertising in the first quarter of 2016. Amazon has an over 70 percent share in the e-book market. Along with Apple and Microsoft, they are now the most valuable companies (in terms of market capitalization) in the world.

The rise of digital platforms has had profound political, economic, and social effects, not least of which on the creators of content. While the internet brought immense benefits to consumers of content, the so-called “creative class”—authors, journalists, filmmakers, musicians, artists—has been particularly ravaged by the digital economy.

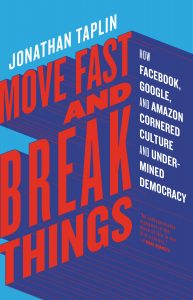

This ravaging, and its roots in the monopolization of content delivery and data in the hands of a few digital giants, are at the heart of the new book Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy by media scholar Jonathan Taplin. In the book, Taplin explores the way in which the internet came to be dominated by a handful of monopoly platforms, and the subsequent capturing of regulators that has since all but ensured their dominance would not be challenged in court.

Taplin, the Director Emeritus of the Annenberg Innovation Lab at the University of Southern California, is well versed in both the creative and the business side of media. Before he became an academic, he worked as tour manager for Bob Dylan and The Band and was a film producer who worked with Martin Scorsese and Gus Van Sant. As such, he has seen first-hand the damage that the internet economy has wrought on working artists like his friend, legendary drummer Levon Helm, who was forced to put on a series of concerts at his home at the age of 70, while dying from throat cancer, in order to pay his medical bills.

Taplin, a former vice president of media mergers and acquisitions at Merrill Lynch, also experienced first-hand how easily entrenched incumbents can stifle innovation in the entertainment industry (it also helps that his father was an antitrust lawyer). In 1996, he co-founded an early video-on-demand company named Intertainer that was forced to fold after one of its shareholders, Sony, partnered with three other major entertainment companies to copy its idea for a rival service. (Intertainer later filed an antitrust lawsuit against the studios and the sides eventually reached an out-of-court settlement).

In his book, part memoir and part manifesto calling for content creators to embrace antimonopoly, Taplin examines the contradictions embedded in today’s digital economy—in which YouTube makes $9 billion in annual revenues, but artists earn more from the sales of vinyl records than online streaming—through the lens of antitrust and the history of monopoly in the U.S.

“The deeper you delve into the reasons artists are struggling in the digital age, the more you see that internet monopolies are at the heart of the problem and that the problem is no longer just for artists,” he writes. “Monopoly control of our data and corporate lobbying are at the heart of this story.”

In an interview with ProMarket,((The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.)) Taplin discussed the rise of monopoly platforms and the part that rent-seeking and regulatory capture play in the digital economy today.

In an interview with ProMarket,((The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.)) Taplin discussed the rise of monopoly platforms and the part that rent-seeking and regulatory capture play in the digital economy today.

Q: How did you become interested in antimonopoly?

It was a very personal story. Levon Helm, who was the drummer for The Band, got throat cancer in 2000. He’d been making a decent living off of royalties from past records that he had made 15 years before, then Napster happened and that just ended. It just so happened that he got throat cancer at that very point. He had to pay for medical bills and he couldn’t go on the road because he could hardly sing.

Eventually he figured out how to do something by having shows at his house, getting a bunch of friends to come and play and calling it the Midnight Rambles. He made a little money, but not enough, just barely paid his bills. It just seemed incredibly unfair to me. That’s how it started.

Internet triumphalists say musicians should make a living by doing live shows now, but that’s how musicians made a living in the 17th century, not the 21st century. That doesn’t make sense to me in a world where there are 5 billion smartphones out there.

I am not worried about Jay Z and Beyonce or Taylor Swift. They’ll figure out ways to make a living—they will play 50,000 seat arenas and charge hundreds of dollars per ticket. But there used to be a middle class in the creative class: working class journalists, musicians. The Band, which I worked for for quite a few years, were not superstars. They were middle class musicians. They made a decent living. Not a great living, but each one of them could clear $100,000 a year, which isn’t possible now. If monopolists end up with most of the money, everyone else is just looking for crumbs to fall down.

Q: How did you get to thinking about the role concentration among digital platforms plays outside of the music business?

A lot of the new businesses, kind of like the old media business, are advertiser-supported. Very quickly, it became clear to me that there are two dominant forces in the advertising business: Google, the most dominant, and Facebook, the second-most dominant. What was happening—not just in the music business but in the journalism business and everywhere—is that these companies were raking off all the cream of the advertising money.

Last year, between Facebook and Google, they took about 80 percent of all new advertising on the internet. That’s shocking. The local newspaper couldn’t make any money from advertising, and the New York Times couldn’t make any money from advertising. Take, for instance, something like YouTube. A musician with a big, successful song, if they could sell a million downloads on iTunes they could make $900,000. If they’d get a million views on YouTube they’d make $900. So it just became obvious that’s where the problem was.

When I began to write the book, I got to see that Amazon was doing the same in the book business. It wasn’t a monopoly, but a monopsony—it could force book sellers to push their prices down, down, down.

I kept coming back to these three—Google, Facebook, and Amazon. All have extraordinary market shares. Google has an 88 percent market share in search advertising and an 80-plus percent market share in Android. Amazon has a 74 percent market share in e-books, and Facebook controls 70-plus percent of mobile social media when you add Instagram, Messenger, and WhatsApp. What more empirical evidence does one need to prove concentration?

Q: In the book, you define Google, Amazon, and Facebook as “classic rent-seeking enterprises.” Can you explain why? And does this definition not apply to the two other major tech firms, Apple and Microsoft, as well?

I do not believe that Apple and Microsoft are monopolies, as they are competing in markets with many players. Google, Facebook, and Amazon are clearly monopolies.

I my view, a rent-seeking enterprise is someone who has control of a specific asset—1.9 billion people, in Facebook’s case—and they extract rent from that in the form of advertising premiums for access to the data that they have. The same thing happens with Google. They have data, and they extract advertising premiums for marketers to get access to this specific asset that they have.

In the case of Amazon, it is a monopsony, so their ability to extract rents is not as simple as it is with Facebook and Google and has more to do with their control of their specific market, which is access to the online book market, whether through e-books or regular books.

Q: You have an entire chapter in the book dedicated to the subject of Google’s regulatory capture. How does regulatory capture fit into the story of the rise of digital platforms?

Well, the strange thing is that Democrats were just as bad as Republicans, maybe worse. Look at the Obama administration—Eric Schmidt was basically Obama’s chief of staff. They’d say “You need someone to run the Patent Office? We have the perfect person,” and so they put the Google person there. “You’re looking for an assistant attorney general for antitrust? We got the perfect person. You want someone at the Federal Trade Commission? Here’s a perfect candidate.”

They were everywhere. According to the Google Transparency Project, hundreds of positions in the Obama administration were filled by Google. And now it’s no different. I hear the new FTC chair will probably be the person Google wants. I think it’s inevitably built in.

Q: Do you think that without regulatory capture, antitrust charges would have been brought against Google?

Oh yeah. An 88 percent market share in search advertising? That is by definition a monopoly.

Q: You propose a number of solutions in the book, such as regulating Google and the other digital giants like they were public utilities. But it also seems that no solution is possible without first addressing regulatory capture.

I agree, but only in so far that perhaps it could come out of the state regulators. State attorney generals could actually bring an antitrust suit if they wanted to, especially ones from big states. Whether California would ever sue Google or Facebook is an open question, but certainly there are other states that might consider it.

Q: At the Stigler Center conference on concentration, you called Google “the closest thing to a natural monopoly I’ve seen in my lifetime.” Can you elaborate?

I would say Google is as close to a natural monopoly as the Bell System was in 1956. If you came to me and said “Hey, I want to start a company to compete with Google in search,” I would say you’re out of your mind and don’t waste your energy or your time or your money, there’s just no way. Classic economics would say that if there’s a business in which there are 35 percent net margins, that would attract a huge amount of new capital to capture some of that, and none of that has happened. That tells you there’s something wrong.

The way the Bell System had to give up all its patents in return for being named a natural monopoly, that to me is a potential solution.

Q: As you point out yourself in the book, natural monopoly can also be a positive thing. For instance, in the cases of the telephone and the telegraph. What is the difference between those natural monopolies and digital platforms?

That was kind of a tragedy of the commons, with competing inoperable telephone networks. It didn’t make sense. Now we’re just in a situation where the amount of capital that would be needed to start a new Google competitor would be so huge or so onerous in terms of competition that it would be very hard to raise that capital. So we’re just dealing with the fact that it’s a de-facto monopoly. Even Microsoft couldn’t get past a 5 percent global market share.

Q: Some, like Peter Thiel, argue that bigness is an essential part of the digital economy, that network effects are key to providing better services.

If Snapchat could really compete on an equal basis with Facebook that would be okay, but every time Snapchat introduces some new innovation, Facebook knocks it off shortly thereafter so that they won’t have any differentiation. And clearly no one has been able to compete with Google.

I’ve talked to venture capitalists and entrepreneurs, and the notion that anyone would finance a new search engine is just laughed at by the venture capital community. Nobody would invest in it.

Even investments that have gone into competing with Facebook have not turned out so well. I would say that the people who are investors today in Snapchat are a little worried. They are getting killed. It truly is winner take all. If Facebook keeps at it, that will discourage more venture capital from going into competitors.

Q: But we do have social networks other than Facebook, just not very successful ones. There are other search engines besides Google. Some could argue that Google and Facebook just have the best product.

Facebook wins now because all your friends are on Facebook. That is the classic network effect. As far as Google is concerned, it wins because that’s where all the advertising money wants to go, so it has the advantage of having such huge cash flows that it is constantly able to improve the product. I would also argue that because the audience is so huge, that has the natural effect of improving the product, meaning the search results.

Q: One of the standard arguments against regulating digital platforms today is that they could be easily usurped by a hypothetical competitor with a much better product. In his book, Thiel calls Google a monopoly, but says that it presents itself as “just another tech company” in order to avoid scrutiny.

On the other hand, when we look at handset makers, for instance, we see that companies that were dominant 10 years ago—Nokia, Motorola—are not even around anymore. Couldn’t something like this conceivably happen to digital platforms as well?

That would mean that in five years Google would not be the dominant search engine, or that Facebook would not be the dominant social network. I wouldn’t make that bet.

Right before he died, Google had Robert Bork write a paper that basically said consumers can switch from Google to Bing at no cost,((“That consumers can switch to substitute search engines instantaneously and at zero cost constrains Google’s ability and incentive to act anti-competitively.” Source: Robert H. Bork and J. Gregory Sidak, “What Does the Chicago School Teach About Internet Search and the Antitrust Treatment of Google?” Journal of Competition Law & Economics 8 (2012): 663–700.)) but that’s not true. If I am really the average Google customer, I have Gmail, I have Google Calendar, Google Maps. I have all these applications that I invested data into which I can’t leave. All my contacts are in Gmail. It’s not costless, the cost of switch is quite expensive. That’s a fallacious argument, since it’s not just a search engine. It’s an ecosystem.

Q: One solution you don’t explore in the book is breaking up digital giants like Google. Why is that?

This just goes to show how quickly the ground is shifting. I now have a piece coming out in the New York Times that explores the idea of breaking them up, but when writing the book, I tried to be reasonable. I thought no one would buy the idea of breaking them up. And now people are raising that idea.