The unprecedented divide between the way that Democrats and Republicans perceive the state of the economy may be linked to two important theories in economics and political science: Rational Ignorance and Rational Irrationality.

How is the U.S. economy doing?

As always, it depends on who you ask.

According to one very large group of Americans, the economy is not doing great and its prospects are pretty bleak. On the other hand, there is another very large group of Americans who are more upbeat about the economy now than they have been in a long time.

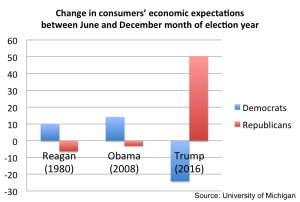

The stark difference between the sentiments of these two groups is not only large, but has another surprising characteristic: the gloomy group was actually very optimistic in October last year, while the members of the more optimistic group, who are now expecting good times, were depressed just five months ago.

By now, you can probably guess who those two groups are: the pessimists are Democrat-leaning voters, as surveyed by the monthly University of Michigan Consumer Expectations Index, and the second group is made up of Republican-leaning voters.

Richard Curtin, who directs the University of Michigan’s survey of consumer sentiment, says that the partisan divide has never had as large an impact on consumers’ economic expectations, although the outlook has occasionally varied according to political party since the survey began in 1946.

According to the New York Times, “Among Republicans, the Michigan consumer expectations index was at 61.1 in October, the kind of reading typically reported in the depths of a recession. Confident that Mrs. Clinton would win, Democrats registered a 95.4 reading, close to the highs reached when her husband was in office in the late 1990s and the economy was soaring. By March, the positions were reversed, with an even more extreme split. Republicans’ expectations had soared to 122.5, equivalent to levels registered in boom times. As for Democrats, they were even more pessimistic than Republicans had been in October.”

One way to explain this divergence between the expectations of Republicans and Democrats is their views on the influence that different economic policies would have on the economy. People who voted for Donald Trump believe that good times are coming and people who voted for Hillary Clinton think that Trump’s policies will derail the economy.

The very first question in the University of Michigan survey is “…are you better off or worse off financially than you were a year ago?” Is the current state of the economy itself a factor in consumers’ sentiments? Well, not this year.

The unprecedented divide between the way that Democrats and Republicans perceive the state of the economy may be linked to two important theories in economics and political science: Rational Ignorance and Rational Irrationality.((See Bryan Caplan, The Myth of the Rational Voter: Why Democracies Choose Bad Policies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007) and “Rational Irrationality and the Microfoundations of Political Failure,” Public Choice 107, no. 3 (2001): 311-331.))

The reason that some political scientists and economists are so suspicious of the ability of regulation and government intervention to fix market failures is the fact that most voters in democracies are usually pretty ignorant about politics, policy, and politicians. True, most of them have their opinions, and they can be passionate about them—but these are seldom based on facts, analysis, or a willingness to collect information about policy and politics.

It is not that voters or citizens are stupid, ignorant, or lazy by nature. They are merely rational. Since the influence of a single voter in most democratic elections is close to zero, and the costs of informing oneself in policy are very high, most people will not have any incentive to become informed.

Still, if people are uninformed or ignorant, why would almost all of them have such strong feelings and ideas about politics? Why would an overwhelming share of Democrats claim that the economy is about to tank, while rationally ignorant Republicans claim that we are heading towards an economic boom?

This is where the theory of rational irrationality becomes useful: voters know that their influence on the outcome of elections and policy are minuscule, yet most of them can derive significant benefit or happiness from being part of a “camp” or a “team” by supporting a specific party. Therefore, even if they are presented with facts and analysis that contradict their preexisting beliefs, or at least suggest a more complicated and nuanced reality, they will continue to support their “team” and look for information that will reaffirm their original beliefs.

In other words, in politics most people are not truth-seekers but rationally ignorant or rationally irrational citizens who make little effort to collect information, and, when they do, they mostly look for selective information that will reaffirm preexisting positions.

Professor Ilya Somin, author of the book Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government Is Smarter (Stanford University Press, 2016), agrees: The results of the last Michigan consumer expectations index, he says, “are quite likely an example of rational irrationality. Instead of judging presidents by the facts, we end up judging the facts by our preexisting view of the president. And it’s not a new phenomenon. In my book, I discuss evidence indicating that, e.g., Republican voters tend to overestimate the rate of inflation and unemployment when Democrats are in the White House, and vice versa. It may, however, be even worse now than in the past, given greater partisan polarization and hatred.”

The ignorance of most citizens is one of the import

ant tenets of the theory of regulatory capture: the tendency of regulators, politicians, and bureaucrats to cater to the interests of special interest groups that are highly informed and not to the interests of the general public.

If the growing polarization of the electorate, the sharp divergence in the way voters perceive reality that is evident in research like the Michigan Index, is indeed an outcome of rational ignorance and rational irrationality, the forces and dynamics that drive regulatory capture may potentially be more salient.

In an environment where a large share of the electorate is less interested in facts, politicians and the regulators that they appoint have less incentive to push for policies that benefit the dispersed public or take on special interest groups. In such an environment, politicians can be almost insulated from punishment following policy failures. Their constituency may not be interested in facts, as long as the politicians are part of their “team.”

Many people see the rise of politicians like President Donald Trump and Senator Bernie Sanders as a sign of the electorate’s growing discontent with the capture of politicians and regulators by special interest groups. Ironically, the kind of polarized electorate that we now see may prove to only exacerbate the dynamics that created the capture that made citizens so angry to begin with.

Research has shown that the chances of the electorate becoming more informed are very low. Huge advances in education and technology in the last century have not improved voters’ rational ignorance in any significant way. Still, even if this is the case, anyone who is interested in economic policy must not ignore the role of ignorance in the capture of politics and regulation and the failure of policies.

Most economists and policy wonks continue to focus all their energy and intellect on questions of which policies are the right ones. Now is maybe a good time to direct some of that intellectual rigor to a very important, yet neglected question: How do we make citizens interested in facts or get democratic institutions to be more accountable and effective in an environment of polarized, ignorant, and irrational voters?