Once a favorite to win France’s upcoming presidential election, François Fillon’s hopes of ever becoming president have been irrevocably dashed in the past two months, following a series of revelations that as a senator he had allegedly used public money originally intended for paying assistants to pay hundreds of thousands of euros to his wife and children for fake jobs as parliamentary aides. Previously the frontrunner, Fillon is now placed third in the polls, after he and his wife were formally charged with several counts of embezzlement and misappropriating public funds.

Many of the revelations that led to these investigations and the derailment of Fillon’s campaign first appeared in the online investigative magazine Mediapart. Back in 2014, Mediapart reported that at least 20 percent of French parliament members employed their immediate family members (hiring family members is legal for MPs in France, so long as the jobs aren’t fake), calculating that 52 wives and 60 sons and daughters were paid by MPs.

The Fillon scandal was the latest in a long string of investigations by Mediapart, a hard-hitting investigative website launched in 2008 by Edwy Plenel, the former editor-in-chief of the French newspaper Le Monde. In the past 9 years, on the back of several high-profile investigations that shook French politics and business world, Mediapart has become one of France’s leading news outlets, with a growing subscriber base that rivals those of some of the country’s major legacy newspapers.

Moreover, Mediapart has also managed to become highly profitable—practically unheard-of for an online investigative news outlet—despite the fact that its business model overtly defies every truism about how media outlets should operate in the digital world: it displays no ads, has no corporate backers, and its only source of revenue are the monthly fees paid by its subscribers. Nevertheless, it still pays its journalists competitive salaries.

Mediapart is the subject of the first in a series of case studies by the Stigler Center at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. It was chosen because of the crucial role independent investigative journalism plays in reducing the power of vested interests and allowing for competitive markets to function properly. The case was written by Dov Alfon, Haaretz‘s editor-at-large in Paris, with a teaching note written by Guy Rolnik, a Clinical Associate Professor at Chicago Booth and Co-Director of the Stigler Center [also, one of the editors of this blog]. On April 13, the case will be presented in a special Stigler Center event that will feature Plenel, his co-founder Marie-Hélène Smiejan-Wanneroy, and James T. Hamilton, the Hearst Professor of Communication and the Director of the Journalism Program at Stanford. The event will be live streamed on the Stigler Center’s YouTube channel.

In a global media landscape that’s characterized by shrinking ad revenues, conventional wisdom has it that investigative journalism is financially unviable. In his recent book Democracy’s Detectives, which examines the economics of investigative journalism, Hamilton writes: “Investigative reporting involves original work, about substantive issues, that someone wants to keep secret. It is costly, underprovided in the marketplace, and often opposed. It is more likely done when a media outlet has the resources to cover the costs, an incentive to tell a new story, cares about impacts, and overcomes obstacles. Changes in media markets put local investigative reporting at risk.”

With the disintegration of journalism’s business model, newspapers were left with fewer resources to fund costly and time-consuming investigations into the misdeeds of politicians and regulators. Since the nature of the web makes it more difficult to exclude access to information, and therefore charge for it, private firms have far fewer incentives to produce it. These developments, scholars like Hamilton say, have made investigative journalism more of a public good.

Can we really expect the market to supply quality investigative journalism that exposes wrongdoing, uncovers corruption, and holds the powerful to account? Many would say there’s simply no demand for it. The success of Mediapart, however, may provide a unique counterfactual.

Plenel, the publisher, editor-in-chief, and leading force behind Mediapart, established the site in late 2007 together with three other partners, all veteran journalists—Laurent Mauduit, François Bonnet, and Gérard Desportes—with the aim of providing a new outlet for investigative journalism that would not be beholden to any political or financial interests. The four were all highly experienced journalists, but had absolutely no experience in business. For this, they relied on Smiejan-Wanneroy, an entrepreneur and marketing expert. They managed to raise €2.9 million prior to launching, mostly from friends, two individual investors, and out of their own pockets, figuring that 50,000 subscribers would allow them to break even.

In order to achieve total independence, Mediapart’s founders chose a unique business model, which includes no advertising and instead relies on subscription fees to pay for content—a risky proposition today and even riskier in 2007, back when most news outlets had yet to erect paywalls and the notion that readers would never be willing to pay for online content was the predominant view.

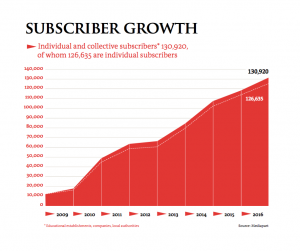

Despite having no source of revenue other than its monthly subscription fee (currently at €11 and initially €9, although various promotional deals have offered reduced fees), Mediapart has been profitable since 2011—three years after its launch. For 2016, it reported a net profit of €1.9 million and a 10 percent growth in revenues. It currently has 140,000 subscribers (compared with 15,000 in 2010), and its subscription revenues have grown more than 18-fold since 2008.

Source: Mediapart

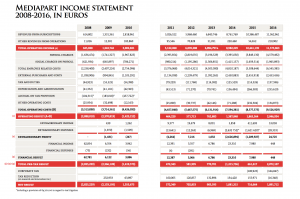

Mediapart’s profitability stands out, even when compared to much older, much bigger, much more established counterparts: Mediapart’s operating margin was 18 percent in 2016, compared with 6.5 percent for the New York Times. Similarly, while the Times’ net margin stood at 1.9 percent last year, Mediapart had a net margin of 16.6 percent.

Source: Mediapart

Mediapart, it is important to note, offers its journalists competitive salaries. According to Smiejan-Wanneroy, who serves as Mediapart’s managing director, its editorial expenses (€5.2 million) account for 61 percent of its annual budget, with salaries (€4 million) being the main component. The annual average cost per journalist, she says, is €90,000 (including social charges), which is slightly higher than other French newspapers.

Despite investing heavily in development, bolstering its video productions, and completing a large purchase of its stocks from investors, says Smiejan-Wanneroy, Mediapart also has €4 million in cash on hand.

Although there is increasing evidence of the immense public value that investigative journalism provides—Hamilton calculates and finds that for each dollar invested in an investigative news story, society can reap over $100 in benefits—many are still skeptical that readers would ever be willing to pay for it.

How was Mediapart able to accomplish what many others before it had tried and failed, namely to find a potentially sustainable—and profitable—avenue for investigative journalism? Some of it has to do with the unique landscape of French media, and some with the unique characteristics of Mediapart itself.

The Bettencourt and Cahuzac affairs

In early 2010, two years into its operation, Mediapart was still a minor player in France’s media industry, with a small readership of merely 15,000 subscribers. The year before, its founders were forced to raise more funds, once again appealing to friends and previous individual investors, and raised €1 million from a hedge fund named Odyssée Venture.

Its first big breakthrough came later that year, after it exposed secret recordings made by the butler of Liliane Bettencourt, heiress to the L’Oreal fortune and the richest woman in France, who became embroiled in a bitter legal battle with her daughter. The ensuing scandal, later known as “the Bettencourt affair,” continues to reverberate—years after it first broke. Among other things, it revealed that Bettencourt received a €30 million tax rebate just as the French government was waging a very public war on wealthy tax evaders, implicated then-budget minister Éric Woerth (who was later charged and acquitted), and for a brief period also threatened then-president Nicolas Sarkozy. Within four months of the initial reveal of the tapes, Mediapart’s number of subscribers grew from 15,000 to 50,000.

In 2012, Mediapart got another breakthrough, when it revealed (again through secret recordings) that Jérôme Cahuzac, then the budget minister in François Hollande’s socialist government, who had spearheaded a major effort against tax evasion, had held a secret bank account in Switzerland for more than 20 years. “The Cahuzac affair” and the massive public uproar it inspired led to Cahuzac’s resignation and eventual conviction; he was sentenced to three years in prison for tax fraud in December 2016.

The Bettencourt and Cahuzac scandals had a profound impact on Mediapart and on French politics. Both scandals revealed the close ties between wealthy donors like the Bettencourts and top government officials, and what many saw as the corruption of France’s political class. They also revealed the culpability of the press, and the ties between established media outlets and political and financial interests. Initially, Plenel and Smiejan-Wanneroy say, the response to both stories by Mediapart’s competitors was indifference and derision: the major newspapers ignored them until, eventually, they could no longer do so.

The Cahuzac revelations in particular, says Plenel, were followed by a long period of dismissal. “It was a battle. For three months, they didn’t want to follow us,” he says. When they finally acknowledged the story, however, what followed was a negative campaign—not against Cahuzac and other prominent tax evaders, but against Mediapart itself for breaking the story. “There was a negative campaign against us in the media, orchestrated by Cahuzac and the Socialist Party, with articles saying that the story is fake and that the reporting was bad,” says Plenel. Only later, once an official inquiry had begun, newspapers agreed to follow-up.

To understand the newspapers’ initial reluctance to follow-up on Mediapart’s exposés, and the rapid pace with which it gained new subscribers, it is important to understand the media landscape into which the site entered in 2008.

Much like their counterparts in other parts of the world, newspapers in France had suffered financial hardships in recent years, as the digital revolution cut into their advertising and subscription revenues.

The difference, however, is that in France the government generously subsidizes print journalism: even when excluding ads from government agencies, subsidies account for 12 percent of the industry’s total revenues, as of 2016. This, in turn, makes newspapers dependent on government aid.

But even with generous government subsidies, newspapers continue to struggle. Financial challenges led to a major wave of industry consolidation, during which four of France’s legacy newspapers—Le Monde, Libération, Les Echos, and Le Nouvel Observateur—were sold to powerful businessmen in highly-regulated businesses that can potentially benefit from political clout.

It didn’t help, of course, that the digital revolution caught French newspapers woefully unprepared, as they were much slower to adapt to the online world than their foreign counterparts. As late as 2014, the web presence of France’s leading publications was still primitive, at best.

Critics also claimed that some of the country’s top journalists were part of the same social circle as prominent government officials and businesspeople, having gone to the same schools together and maintaining strong social ties.

Combined, these factors led to a widespread feeling that the French press had largely abandoned its watchdog role. In 2016, France was ranked 45th on the World Press Freedom Index (in 2015 it was ranked 38), behind such countries as South Africa (39) and Botswana (43). “Though journalists in France are generally free and their work protected by the law,” read the report, “the media landscape is basically made of groups whose owners—industrialists in particular—may have other objectives in mind than defending editorial independence. Political and financial pressures are more and more frequent. Reporters have sometimes been attacked when they covered political meetings or other events.”

Consequently, the media lost the public’s trust: according to the 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer, only 33 percent of the French public trust the media, compared with 38 percent in 2016.

All this, however, made it easier for Mediapart to stand out. The initial refusal of established media outlets to follow-up on Mediapart’s exposés, says Plenel, helped Mediapart differentiate itself and attract readers. Readers interested in learning about the allegations against Cahuzac had to turn to Mediapart, with its strict paywall, and become subscribers. By 2014, Mediapart’s subscriber base grew to 100,000.

As readership was steadily growing, however, Mediapart became entangled in a long and heated tax battle with the French government that revolved around the definition of journalism in the digital age. At its heart was the reduced VAT that French newspapers pay, essentially a government subsidy. When Mediapart first launched, the French law had no special provision for online news outlets. Mediapart defined itself as an online newspaper, and so it paid the reduced rate of 2.1 percent paid by French newspapers, rather than the 19.6 percent rate paid by other non-journalistic sites, like retail platforms. But in 2013, the French Treasury argued that Mediapart was in fact a platform and demanded that it pay €4.7 million in back taxes and fines. Plenel saw this as revenge for the Cahuzac story, pointing out the ties between Cahuzac and several tax officials involved in the case.

The French parliament changed the law in 2014, allowing digital news outlets to pay the same VAT rate as print newspapers. Yet the Treasury insisted on the millions it said Mediapart owed the state, arguing that the new legislation was not retroactive. The case is still ongoing.

According to Smiejan-Wanneroy, the total amount relating to the case, €4.7 million, was provisioned in Mediapart’s 2014 and 2015 accounts and the outstanding VAT was paid while awaiting the outcome of legal recourse. She expects Mediapart to win the case and receive the amount back with interest.

With success, the attitude toward Mediapart among the French press also began to change, as newspapers started to follow-up on its stories and TV and radio news programs began to emulate its reporting. “It has taken more than 8 years, but recently [the attitude] started to change,” says Smiejan-Wanneroy. Mediapart, she says, is now in the same league as the bigger media outlets, like Le Monde.

Plenel, however, still thinks Mediapart stands alone among French media outlets. “In economics, in politics, even in our coverage of sports, we reveal what the powerful people want to keep secret,” he says. “Our media culture is that in all areas, we give people information against the oligarchy. In this culture of investigation, I think we are alone.”

Is Mediapart a model for a sustainable investigative journalism?

Mediapart has been an ambitious project from the get-go. Plenel and his partners recruited 24 reporters (the number has since grown to 45, plus roughly 30 support staff) and set a minimum of publishing at least five hard-hitting stories a day. Since then, it has grown beyond its text-based roots to encompass videos and photojournalism, as well as an active blogging platform.

What sets it apart, though, is that unlike other media outlets, what drove Mediapart’s success was its investigative journalism, as the impact of the Bettencourt and Cahuzac stories made Mediapart a leading destination for stories on political corruption and corporate wrongdoing in France.

This emphasis on investigative journalism as a driver for profit is no accident, but an integral part of the Mediapart business model. While other news outlets are working to improve their ad services, attempting to glean as much information as they can about their readers, the leaders of Mediapart know very little about their audience.

“We have nothing to sell to them, so we don’t ask anything about their lives,” says Smiejan-Wanneroy. “When we launched Mediapart, we asked the readers some questions: year of birth, occupation, address, and some others. We discovered very quickly that the more you ask, the more you risk losing the people who just want to read an article. If you are a subscription-based outlet, you must not ask lots of questions. We give subscribers the opportunity to provide some information after they sign up, but only a part of them actually do it. We have nothing to sell to our readers and we respect the privacy of our base of subscribers, so we don’t ask anything.”

The question, however, is whether Mediapart’s model is sustainable and can be replicated outside of France, or whether it is a unique anomaly in an otherwise grim landscape for investigative journalism. Investigative journalism is crucial for the proper function of democracy and free markets, but its public good nature can clash with its chances of being profitable.

Mediapart’s success seemingly creates a compelling case that there can in fact be market solutions that would fund quality investigative journalism, but Mediapart owes a great deal to the unique characteristics of the French media market: the government subsidies it enjoyed before it was forced to pay them back (today it continues to benefit from a reduced VAT rate), the slower adoption of digital technologies that made France’s newspaper industry ripe for disruption, the lack of local competition due to close ties between the political and media establishments, and the initial hostility toward Mediapart which only served to enhance its profile and set it apart.

Nevertheless, even when accounting for all the above, Mediapart’s success is worth noting and shows that there is in fact a consumer demand for quality journalism that speaks truth to power.