Northeastern economist John Kwoka: “There’s really an absence of evidence to the contrary.”

Concerns over rising concentration in the American economy have become increasingly prevalent among economists, policymakers, and investors over the past year. Following a spate of articles that described diminishing competition as “one of the biggest problems facing America’s economy,” the issue has gained traction in the political discourse as well. But is the notion that America has a concentration problem supported by empirical evidence? This, said economists during the opening panel of the Stigler Center’s conference on concentration in America, appears to be the case.

“It’s the totality of evidence, rather than any single study, that underscores the issue [of rising concentration],” said Northeastern University economist John Kwoka, one of the featured panelists. “There’s really an absence of evidence to the contrary.”

The panel featured Kwoka, the Neal F. Finnegan Distinguished Professor at Northeastern University; Roni Michaely, the Rudd Family Professor of Management and Professor of Finance at Cornell University; Fiona Scott Morton, the Theodore Nierenberg Professor of Economics at Yale University and former chief economist at the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division; Carl Shapiro, the Transamerica Professor of Business Strategy at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley, also former chief economist at the DOJ’s antitrust division; and Barry Lynn, the director of New America’s Open Markets program. The event was moderated by Patrick Foulis, New York Bureau Chief at The Economist, who opened the panel with an anecdote on the prevalence of concentration and the ambiguity surrounding the issue.

“On the way here I took an Uber to the airport. On the way, I used an iPhone, which has a 40 percent market share of smartphones in the U.S. I took a United flight, which is part of four airlines that some have called a cartel in the U.S. On the flight, I watched DirecTV, which is a media company that was bought by AT&T a couple of years ago. I checked into an InterContinental hotel, which is part of an industry that’s consolidating rapidly.

“But to get a sense of the ambiguity, one can think of the same set of incidences in a slightly different light: Uber got its market share by losing a couple of billion dollars a year, essentially subsidizing people like me. Apple is part of an industry where traditionally the leader—Nokia, Motorola, BlackBerry—only lasts a few years. United is part of industry that investors worry is about to have a price war. DirecTV, investors worry, is an old technology that Netflix will blow apart. InterContinental is threatened by the likes of Airbnb and internet travel aggregators. So it’s not a simple question to answer,” said Foulis.

In recent years, a growing body of research has suggested that competition has weakened across U.S. industries, and that this is having adverse effects on the economy and on consumers. In April 2016, President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers issued a report that claimed competition has declined in numerous sectors within the American economy. A recent paper by Gustavo Grullon, Yelena Larkin, and Roni Michaely found that more than 75 percent of U.S. industries experienced an increase in concentration in the last two decades. Numerous studies have argued that rising concentration among airlines, banks, wireless carriers, and hospitals (along with many other industries) has had anti-competitive effects.

Many economists, however, dispute the claims that America has a concentration problem. Some, like University of Chicago professors Sam Peltzman and Dennis Carlton, argue that while the evidence points to a rise in concentration, there is not enough evidence that rising concentration leads to adverse economic effects, and that concentration does not necessarily mean lack of competition or decline in quality. Others dispute the data itself. In a recent (forthcoming) interview with ProMarket, Chicago Booth professor (and former chairman of President Obama’s CEA) Austan Goolsbee said that the evidence that points to a rise in concentration “comes from court cases or non-representative samples and is filled with ambiguity and myth.”

During the Stigler Center panel, most panelists agreed that the claims that concentration has risen in America are supported by empirical evidence. Questions such as what this rise in concentration means for competition and for the U.S. economy and how enforcers and policymakers should deal with it, however, were the subject of a lively debate.

“I’ve yet to see a single study that shows a decline in concentration [over the last two decades],” said Kwoka, whose recent studies and 2015 book Mergers, Merger Control, and Remedies in the United States: A Retrospective Analysis (MIT Press) focused on the effectiveness of merger policy. In a 2012 paper, Kwoka studied 48 mergers that were approved by regulators and found that 36 of those were followed by price increases.

Arguing that “a substantial body of evidence” shows a rise in concentration in major sectors of the U.S. economy, Kwoka cited the CEA brief (whose categorization, he said, was “too broad for economists’ liking, but indicative nonetheless”) and The Economist’s March 2016 article that stated that “America needs a giant dose of competition.” Kwoka also referenced a recent study by David Autor, David Dorn, Lawrence Katz, Christina Patterson, and John Van Reenen that linked concentrated winner-take-all markets with the fall in the labor share.

However, Kwoka noted, studies “do not find that concentration has risen everywhere.” The industries where concentration has risen most dramatically, he said, “represent perhaps 10 percent of the economy. But it’s an important 10 percent, which in the past had not been nearly as concentrated.”

What caused this rise in concentration? It is possible, Kwoka said, that rising concentration is partly the result of improvements in efficiency or service quality, or that innovation and consumer preferences have made certain sectors more concentrated, “and there are certainly sectors where that’s true.”

The other reason for rising concentration, he said, are barriers to entry: “There’s considerable evidence that the rates of new business formation have declined in this country. If new entries have diminished, but exit rates have remained more or less constant—and that appears to be the fact—then we would expect a decline in companies in a variety of such industries, and I believe the evidence supports that as well.”

Kwoka offered a number of other reasons for the rise in concentration. Beyond the “traditional economic reasons” like network effects and winner-take-all-markets, there are “strategic reasons,” such as exclusionary behavior by firms. “The ability of companies to build and enhance barriers to entry has grown, and there is evidence that companies have focused on this, as opposed to traditional price raising opportunities, and [there is] considerable evidence that they are much more successful in doing this,” he said.

Another reason for the increase in concentration, added Kwoka, is America’s “too permissive” merger policy. “There has been a documented narrowing of focus among merger enforcement agencies. Data show that for industries where there are 5 or more firms remaining after a merger, challenges at that level have virtually disappeared, which gives rise to broad increases in concentration. A number of studies I’ve compiled and synthesized show that even after review by the agencies, mergers have resulted in price increases.”

When asked about the threshold at which economists and policymakers should be worried about consolidation, Kwoka said that “the search for magic numbers is a misguided effort.”

“Much more than 10 percent”

Cornell professor Roni Michaely also pointed to a rise in concentration but disagreed with Kwoka’s estimate regarding its scope. Rising concentration, said Michaely, “is much more widespread than the 10 percent figure that was mentioned before.” Michaely cited figures showing a dramatic rise in two of the leading measures of market concentration—the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) and the four-firm concentration ratio (CR4)—over the past 20 years.

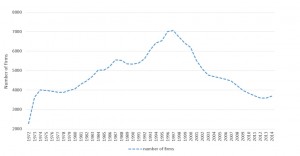

Concentration, said Michaely, has increased significantly in most U.S. industries over the past two decades. One consequence of this is an increase in profitability. Some of it, he said, might be due to increases in efficiency, but most of it stems from an increase in profit margins. Another is a decline in the number of publicly traded firms. “U.S. markets lost over 50 percent of their public traded firms [since the mid-1990s],” said Michaely, who added that “we see a three-fold increase in the average and median size of (publicly traded) firms in real terms.”

Michaely also cited the results of an exercise, included in his paper with Grullon and Larkin, in which they test a long-short investment strategy: going long on industries that experienced the highest increase in concentration in a given year and shorting industries that experienced the lowest concentration increase. This strategy, said Michaely, would yield an alpha of 9 percent a year.

“If markets are contestable, we should not see something like this,” he said.

Like Kwoka, Michaely argued that the rise in concentration can be attributed to lax antitrust enforcement. Despite notions that the internet will democratize the economy, the same trends that affected the rest of the economy apply to the tech sector too, especially as concentrated firms accumulate more patents: “The more concentrated the industry, the more the members

of this industry are accumulating patents and value of patents.”

“You have to be careful”

UC Berkeley economist and former CEA member Carl Shapiro, struck a skeptical note. Economists and policymakers, he said, should be careful when considering data and studies that show that concentration has increased and has adverse economic effects, saying there isn’t enough evidence to support that view.

Like Kwoka before him, Shapiro also criticized the Economic Census data that the CEA report largely relied on as too broad, saying: “I am picky about what counts as a market.”

“Almost all the data people talk about goes back to Economic Census,” said Shapiro. “What did the Council of Economic Advisers do? Somewhat embarrassingly, they looked at the 50-firm concentration ratio in two-digit industries. I don’t know any Industrial Organization economist who thinks that’s very informative regarding market power. At some broad level, larger firms are having a larger share of economic activity—I think that’s true, but that doesn’t directly tell us about competition or concentration in markets where market power can be exercised,” said Shapiro.

“There is definitely a decline in business start-ups—I think a bunch of it is things like there are fewer dry cleaners opening up, [and] we’ve had problems following the Great Recession because people don’t have as much equity to start a business. I am not sure that’s an economy wide competition problem. It’s an issue, but is that where the competition problem is? I doubt it.” Shapiro also defined the four-digit data used by The Economist as too broad and added that looking at the four-digit data, concentration does not seem like “too much of an issue.”

Later, he remarked: “The data on efficiencies of horizontal mergers in particular is very thin.”

Shapiro summed up the opposing views on concentration and its effects as a disagreement between two different worldviews: “The antitrust economists, we shrug our shoulders. But maybe politicians, policymakers think that’s a problem. Is it a problem because of market power or because of political power, or because these broad concentrations are going to lead to more market power? Who’s right on this? Somebody is missing something. But the data everyone is looking at, the Economic Census data, you have to be very careful with that.”

Despite his reservations about the data, Shapiro also said that “antitrust economists are mistaken to shrug their shoulders at increases in CR4 if CR4<50 and in HHI if HHI<1500. On the other hand, the press, politicians and some policy makers are mistaken to claim the data show a worrisome increase in industrial concentration in America.”

The fact that over the past 30 years corporate profits before tax have gone up by 50 percent, said Shapiro, is “more of a puzzle.”

“How persistent are high profits at the firm and industry levels, and have entry and expansion become less effective at eliminating rents to incumbents?,” he asked.

Yale University economist Fiona Scott Morton also struck a cautious note, agreeing with Shapiro while some data point to an increase in concentration, it is still too early to determine whether this has adverse effects.

Morton stressed the role of regulation and regulatory capture in the increase of U.S. concentration. “Behind every rule we have a lot more dollars today than we had 30 years ago and we’re not increasing the size, capability, or cleverness of the bureaucracy in proportion to that. The result is that it’s worth spending on regulation, and you get regulatory capture. Firms lobby, and convince, and take people out to lunch and hire them later in order to get regulations that protect them from competition.”

Morton mentioned cable companies, pharmaceuticals, and airlines as “industries where incumbents look to the government to protect them from competition.” If major sectors of the U.S. economy managed to capture regulators, she said, “then we can end up with the pattern that we see, of higher profits and less entry.”

What should be done? Tighten antitrust

As for the question of what should be done about rising concentration, all speakers supported strengthening antitrust enforcement, though they differed on the degree to which antitrust enforcement should be increased. In some areas of the economy, Shapiro said, antitrust should be “moderately tighter than it is now.”

He also suggested that “if the government didn’t have the burden of proof, and the companies had the burden of proof to show that a merger is pro-competitive, it would be a lot harder to do a merger.”

Lynn, however, called for much broader action that relies on renewed support for antimonopoly measures: “Is there a monopoly problem in America? When you talk to the public and to policymakers, the answer is ‘yes’.’ When we started our work 15 years ago, this was not the case.”

Drawing from the rich history of antimonopoly in the U.S., Lynn defined concentration as a political and not just economic risk, and called for a much tighter antimonopoly policy based on the Brandeisian model. “From the Boston Tea Party onwards, antimonopoly was one of the key tools we in the U.S. used to keep ourselves free,” he said.

With the overhaul of the merger guidelines in the early 1980s, Lynn said, the U.S. underwent a “philosophical revolution” that dramatically affected antitrust policies. “35 years ago, we drastically changed how we deal with monopolies. The idea was to get this out of the hands of politicians, and into the hands of economists,” said Lynn. “First we moved from a Brandeisian view to a Borkian view. Then we went through digitization, which created super dominant companies. The first shift created Walmart, and the second created Google and Facebook”.

“Today,” said Lynn, “it’s absolutely clear to anyone with eyes in their head that what we did 35 years ago is not working for the average citizen.”

Much the debate portion of the panel revolved around the question of how antitrust enforcers should deal with digital platforms. Michaely cautioned that “solutions are not simple,” but advocated strong antitrust enforcement—“not just for mergers.”

“Mega companies may have to share their data, or maybe even broken up like AT&T,” he said.

Morton and Shapiro took a much more cautious approach. When asked about big Silicon Valley firms routinely acquiring smaller firms as a way to spur R&D, Shapiro said: “The worry is that big tech firms could see the threats coming around the corner before the government, gobble them up, and eliminate the threat. That’s a serious worry. But if you see the acquisitions Google has made, you’d be hard pressed to find which of those you want to stop. It’s very hard to know how to do that type of enforcement effectively.”

Morton also argued against aggressive action when it comes to tech mergers: “When you have a company with six employees and $100 in revenue, and you say ‘we’re worried about this merger because this is the next big thing that’s going to overturn Facebook,’ that case is very difficult to win in court. If we as a society decide these mergers are dangerous, we have to really change the laws.”

“I think we need a little bit of a reset to make sure focusing enforcement on the problems that we have today and not the problems we had yesterday. Is much easier to litigate something that has precedent and that you understand. New technologies are more risky for the agency and for the development of economic theory,” said Morton.

Morton added that “the economics profession doesn’t have a good answer to whether large mergers reduce R&D.”

Lynn, on the hand, said the existing antitrust tools can be used effectively without new legislation and called for policymakers to challenge large tech mergers, citing historical precedent: “120 years ago, we didn’t talk about the dangers of railroad companies buying this grain elevator or that company. What we did is we prevented the network monopolies of that era from buying all companies. Google, Facebook, and Amazon are the railroads of today. They are utilities, and there is a simple way to deal with this: we prevent them from vertically integrating.”