A new Stigler Center paper shows the extent of sexism in the financial industry: although male financial advisers are three times as likely to engage in misconduct and twice as likely to be repeat offenders, women are far more likely to be punished for it.

It is not every day that an academic research paper has the potential to make many readers uncomfortable and perhaps even angry. For some readers, not just staunch feminists, a new Stigler Center research paper by Mark Egan, Gregor Matvos, and Amit Seru titled “When Harry Fired Sally: The Double Standard in Punishing Misconduct” is capable of doing just that. To be sure, it had that effect on the author of this review.

Last Wednesday, March 8, was International Women’s Day. Most major media outlets dedicated news and analysis to the persistent gender wage gap that exists all over the world. According to one estimate, at the current (slow) pace of progress, the gap between men’s and women’s compensation will take over 70 years to close.

Yet, both the real magnitude and the cause of that gap are highly debated. For example, Chicago Booth professor Marianne Bertrand and co-authors claim that at least a third of the gender wage gap for young professional women in the finance and corporate sectors is due to the career interruptions women are more likely to take. Controlling for these interruptions, they find no statistically significant difference in wages between male and female MBAs 10 years out. Thus, is the gender wage gap just the consequence of unmeasured differences in the characteristics of the male and the female labor force or is it the result of discrimination against women?

The new Stigler research paper indirectly answers this question by examining another potential source of women’s discrimination in the labor market: the way they are treated when involved in misconduct. The research finds that women are severely discriminated against—and more so when their bosses are men.

The researchers thoroughly examined one of the largest industries in the United States: the financial advisory industry. In a previous paper, Egan et al. documented how prevalent misconduct is in the industry and the significant consequences that it has on the labor market for financial advisers. In their new paper, they examine how companies’ managers and owners treat employees who are involved in misconduct, depending on their gender.

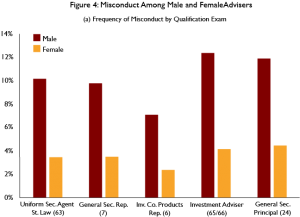

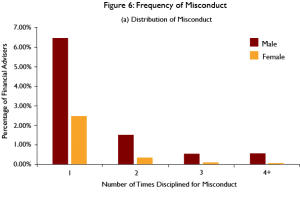

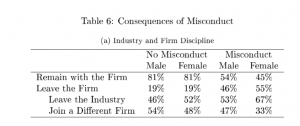

Their research shows that male advisers are more than three times as likely to engage in misconduct: on average 1 in 11 male financial advisers have records of past misconduct, compared to only 1 in 33 female advisers. Yet, female advisers face much more severe punishments at both the firm level and the industry level following an incidence of misconduct. When they commit misconduct, female advisers are 50 percent more likely to be fired or separated from their jobs; they face longer unemployment spells and are 30 percent less likely to find a new position in the industry within one year.

Conditional on not being fired, past misconduct also weighs more heavily on women than on men: male advisers with recent misconduct are only 19 percent less likely to be promoted relative to other male advisers, while female advisers with recent misconduct are 67 percent less likely to be promoted relative to other female advisers.

For this evidence not to be driven by a bias against women, we would need to see that women’s misconduct is much more severe and/or that women have a much higher tendency to repeat misconduct. It turns out that the opposite is true: male advisers are twice as likely to be repeat offenders, and they are engaged in misconduct that is 20 percent more costly for the firms to settle.

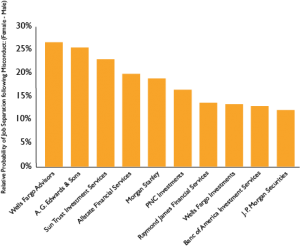

If this evidence of bias against women was not sufficiently compelling, the authors also show that the degree of bias changes with the gender composition of the senior executives. Female advisers at firms with no female representation at the executive/ownership level are 42 percent more likely to experience job separation than male advisers at the same branch following an incidence of misconduct.

By contrast, firms with equal representation of male and female executives/owners discipline mal

e and female advisers at similar rates. Firms with a larger male representation at the executive/ownership level are also more forgiving of misconduct by male advisers in hiring decisions. The bottom line is pretty simple: male executives seem to be more forgiving of misconduct by men relative to women.

This systemic discrimination against women financial advisers in cases of misconduct raises an important question: Why don’t some firms specialize in hiring more women who have been punished by the incumbent firms?

One can think of at least two explanations. The first is that the industry is dominated by male executives: the executives’ taste for hiring men may interfere with their incentives to maximize profits, and investors cannot notice or monitor that. Another possibility is that the market is not aware of this discrimination, since this dataset was put together for the first time by the authors.

In any case, this research is useful not only in exposing the problem but also in resolving it. Based on its findings, the owners and executives of financial advisory firms should ensure equal representation of the two genders at the top of their firms, if not for equity considerations then at least for a profit motive. If they do not, the selection of their employees will be inefficiently distorted.

More importantly, customers can make a difference too. Based on this paper, they should start trusting more women financial advisers: they are much less likely to cheat because they are both intrinsically more honest and more likely to be fired if dishonest. If customers exhibit a strong preference for women financial advisers, the unfair discrimination will be soon eliminated. This is the reason why it is so important that the findings of this paper are widely diffused.