Bernard Yeung, one of the predominantly non-U.S.-born economists who laid the foundations of scientific research on economic power concentration, offers insights relevant to the U.S. economy. Part 1 of a three-part interview.

Bernard (Bernie) Yeung, the dean of the National University of Singapore Business School—and frequent collaborator of Randall Morck, a professor at the University of Alberta School of Business—is a member of a relatively small group of scholars who studied how corporations were growing by using their economic and political power rather than by making their products and services better and cheaper.

As far back as March 1996, almost 21 years ago, Yeung, along with Stefanie Lenway (University of St. Thomas, Minnesota) and Morck, published their influential paper “Rent Seeking, Protectionism and Innovation in the American Steel Industry,” which showed how trade protectionism rewarded the declining U.S. steel industry for poor performance.

In November 1998, Yeung and Morck collaborated with David Strangeland (University of Manitoba) and showed in their paper, “Inherited Wealth, Corporate Control and Economic Growth: The Canadian Disease,” how the Canadian economy was partly controlled by families with inherited wealth using pyramidal holding structures.

In August 2004 the pair co-authored with Daniel Wolfenzon an even wider analysis, covering more countries. Their paper, “Corporate Governance, Economic Entrenchment and Growth,” showed how pyramidal structures, cross shareholding, and super voting rights are common and used to control corporations and, in some cases, even whole industries.

Other scholars who studied these topics include Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes and Andrei Shleifer, and Raghuram Rajan and Luigi Zingales.((Also see.)) The fact that all—including Yeung and Randall—are not native-born Americans (they were born in Argentina, Mexico, Russia, India, Italy, Hong Kong, and Canada, respectively), may be related to the absence of such concentration in the U.S.

Yeung experienced anti-competitive and market-distorting behaviors as a teenager in his native Hong Kong, which was then still governed by Britain. Immediately after high school, Yeung was employed as a clerk at Chase Manhattan Bank (now part of JPMorgan Chase). Although he was a junior employee and still had no academic education, he quickly realized how British interests ruled the Hong Kong financial and non-financial economy. He calls it “colonial bullying.” This experience, he says, helped shape his interest in economics.

In his career path, Yeung crossed the Pacific a few times, always using his deep knowledge of Asian economies to learn more about how economies operate worldwide. In February 2016, he again collaborated with Morck and published, together with Chen Lin (University of Hong Kong) and Xiaofeng Zhao (Lingnan University, Hong Kong) a paper titled “Anti-Corruption Reforms and Shareholder Valuations: Event Study Evidence from China.” In this paper, the authors mention the 2012 Chinese anti-corruption campaign and conclude that market development and anti-corruption reforms are mutually reinforcing.

We recently invited Yeung to the Stigler Center and sat with him for an interview, in which he shared his expertise as well as his thoughts on the scientific method and some of the basic challenges technology is presenting to business, regulation, and politics.

The interview will be presented in three parts. In this part, we discuss how Yeung’s personal history affected his career choices, his extensive work with Morck, pyramids, concentration of power, power politics, and business entrenchment in the U.S. In the second part, we talk about the scholars who laid the foundations of the power concentration literature, Southeast Asian economics and politics, how economic conditioning plays a role in the accumulation and use of excessive economic power, and the erosion of the U.S.’s wariness of big business. In the third and final installment, we discuss the influence big businesses have on the market for ideas, why governments are actually comfortable with big businesses, the distortions in the banking sector, and the lessons Uber has for business and academia.

Guy Rolnik: Together with Professor Randall Morck, you dedicated a lot of time to researching the role of power in corporate governance and pyramids—these vast business conglomerates that dominate the capital markets in many economies around the world. There is not a lot of literature on this. What drew you to those issues? How did you develop this interest?

Bernard Yeung: It was something that I felt since I was a teenager.

I was born and grew up in Hong Kong. Hong Kong, in spite of Westerners saying that it’s a free market, was a place controlled by the British commercial interest. It really is a colony. The banking sector was totally controlled by what is called today HSBC, Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, along with Standard Chartered. There were three banknote-issuing banks in Hong Kong then: HSBC, Standard Chartered, and Mercantile Bank Ltd, which was acquired by HSBC in 1959 but still issued banknotes until 1974. These three banks controlled a committee which regulated interest rates in Hong Kong in those days. In my recollection, when it came to finance, banking was the only game in town, and the dominant player was HSBC, followed by Standard Chartered; that was the Hong Kong financial market all the way until the ’80s. Even Chase Manhattan, the bank I worked for in 1974, had to rent a license to run its bank outfit in Hong Kong.

I worked in Chase Manhattan Bank. Every other Wednesday morning, I received a sheet from the Hong Kong Bank a

nd the “banking committee” that told me what interest rate to use. It was weird—I had to understand what all that means.

GR: What did you do in Chase?

BY: I was just a clerk in the remittance department. I needed to know what interest rates to use in handling fixed time deposit, one of my assignments.

GR: This was your first job?

BY: I just finished high school. The government, together with the British interest, they bullied some of the local upstarts. There is a very famous family in Hong Kong called Fok, which was bullied by the Hong Kong government. Allegedly, the government forced them to sell some properties. It was really a monopoly. In my opinion, HSBC and the like monopolized finance and the government gave privilege to British interest, including privileged access to the profitable property market. I did not know much as a high school graduate, but that was my impression.

There was something funny about it. Some big shots making all the calls all the time. They made calls advantageous to them. The Hong Kong stock market rose and collapsed in 1973. The one that benefitted the most is HSBC as I understood it, collecting fees and handling IPOs.

I felt that might be what colonial bullying is. There were many, many small companies, mom-and-pop shops, who could not easily get financing or land. They had to pay big rents. But a light manufacturing sector, e.g., in clothing, emerged. The manufacturing was mostly in the Northern part of Kowloon, an area that was supposedly rented from China in 1898.

GR: When did you start researching this?

BY: After my second tenure with the University of Michigan, in ‘92. My first tenure was at the University of Alberta, a lovely place.

I started working with Randall Morck in 1986; we were colleagues at the University of Alberta. We have been working on firm-level analytics focusing on value creation or destruction. For example, our work on foreign direct investment focused on conditions under which multinationals’ foreign expansions create share value. We also worked on how trade protection destroys value. Using firm-level based empirical evidence in the steel industry, we showed that protection lobbying firms’ CEOs got a pay hike after protection, senior worker wages went up, jobs were not created, and R&D spending slowed down after protection was secured.

We started to focus on how the institutional environment changes company behavior; we believe there are some big issues. We started on two projects almost simultaneously. One was to talk about concentrated control. Randall and I were both very interested in that: there was some Canadian experience that Randall was very familiar with and the experience I had in Hong Kong rang a bell too. The natural thing to say was that market environment affects behavior. But our experiences suggest that the market environment was created by a dominant player, or a few of them. Now you can immediately see how these are connected. The dominant players’ behavior can define a market’s environment and they may even be able to influence rules and regulations that fundamentally influence the market. At the end, it is natural to suspect that they act in a way that favors themselves and discriminates against others.

The other thing that we worked on is the information content of stock prices. The capital market is the core of an economy responsible for guiding resource allocation and thus whether it has information is important. We show that equity prices’ information content is lower in an environment where its government does not respect private property rights well, investors’ rights are not well protected, disclosure requirements are weak, etc. Clearly, the Law and Finance literature was a great help in this—thanks to the La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny group, and others.

GR: How do you define concentrated control?

BY: Concentrated control does not have to mean only equity. Concentrated control occurs when a few control a lot of corporate decisions. Thus, people tend to think of “control rights.”

In a similar vein, someone can have a lot of high-level influence or direct control on measures that affect people’s economic freedom: a high-powered person, likely a politician, may be able to shut down trading in organized markets or impose barriers on flows of goods, services, and capital. This can be a process: someone gets rich, they gain a lot of economic power; they use the economic power to occupy the goods market and also to bias the development of capital markets to their favor. Preserving their market share and control of the capital market is important. They are not so keen on reforms that create transparencies and good institutional rules that allow the capital markets to finance the most deserving people. These people can become their competitors in all kinds of ways.

Theoretically, the capital market is built on savers, borrowers, and someone in between to match [them] up. But in a closed kind of capital market, if I monopolize all the savings, all the money comes to me—not to the best guy. I preserve my economic power and possibly political power. It is more important than monopolizing goods markets. Dominating the capital market is like controlling the upstream of wealth creation. Controlling wealth creation will protect my economic and political power. This is how I felt about my observations, causal as they were, in Hong Kong as a teenager.

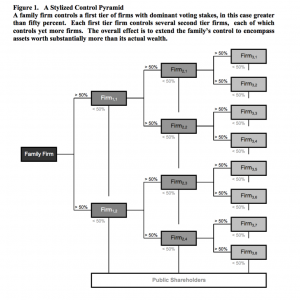

Randall and I discussed this a lot; he is a stimulating colleague and our discussions push each other to think deeper. For example, we discuss how someone can control so much of an economy. No one is rich enough to take all of the economy. This is where the pyramids and all the mechanisms to expand your span of control with very little equity appear. The story emerged quite nicely: a few people in the pyramid apex find ways to expand their control. With some equity they control a lot of corporate assets. They often get into cash-cow industries like utility, transportation, properties, etc.; we can check what rich tycoons control. And with that degree of control, they aim at even controlling the capital market and a large part of the economy.

And in a situation like this, upstarts have no faith

in the future. Not seeing the possibility of getting finance, so they make little upstart efforts to begin with. That’s how you may end up having stagnation.

The established may be good at the beginning, especially when the founding parent is around. But new ideas often have to come from outside and from people who can see most of the benefits of their ideas. These do not apply to big corporations. Furthermore, when leadership in the executive suite is chosen not just by merits and blood ties and relationships matter, the capabilities of the executive suite will, over time, not be as good as the founding parent.

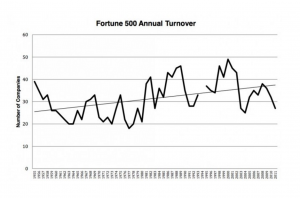

Now you can see how the pieces fall into place. When there isn’t enough churning of big corporations, the economy stagnates. If the members of Fortune 500 were always the same companies, the U.S. would not be what it is today.

GR: What was your first paper in this strand?

BY: The first paper [was] “The Canadian Disease,” which appeared as an NBER working paper in 1998 and later in a 2000 book Randall edited, Concentrated Corporate Ownership.

We used the term “Canadian disease” to describe big family firms who expanded control using pyramids and so on; pyramids were there in Canada. These firms underperformed compared to their American counterparts. We go from there to say if an economy has a lot of old money it does not grow well.

GR: When you wrote the first paper, how much existing literature was there on those issues?

BY: Maybe not a lot. I believe some great scholars were already working on that. First, we have to be thankful to the stimulating work by La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer on “Corporate Ownership Around the World” and also De Soto’s book, The Other Path: The Invisible Revolution in the Third World. Second, credit to Randall who saw the need for a conference and a book. Third, very good scholars were thinking about this simultaneously. Maybe Daron Acemoglu, Jim Robinson, and Simon Johnson started their work at the time. Maybe Luigi Zingales and Raghuram Rajan were already working on their famous 2003 JFE paper “Great Reversal: The Politics of Financial Development in the 20th Century” and also their 2003 book, Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists: Unleashing the Power of Financial Markets to Create Wealth and Spread Opportunity. They and many others—e.g., Faccio, Djankov, Lang, Stijn, etc.—all contributed.

There were many wonderful scholars working on the topic. I cannot really name them all. Suffice it to say that there was a burst of energy and insightful and stimulating research results. I feel blessed that we were in the crowd.

GR: You said there was not a lot of literature when you started. Which intellectuals were you building your ideas on when you started writing those papers?

BY: Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means. Their book, The Modern Corporation and Private Property; it mentioned concentrated control. It’s also worth mentioning Bradford DeLong’s 1990 paper, “Did J.P. Morgan’s Men Add Value? An Economist’s Perspective on Financial Capitalism.” I would add again LLS’s “Corporate Ownership Around the World,” and De Soto’s The Other Path.

GR: In your famous paper, “Corporate Governance, Economic Entrenchment and Growth,” you say that in most countries, except the U.S. and the UK, most of the capital markets are controlled by pyramids. This is a very dramatic phenomenon. In most economies around the world capital markets, and often the economies as well, are actually controlled by those pyramids—economically and politically. Yet, it was not until the late ’90s and the beginning of the 2000s that significant literature appeared. Is there a huge elephant in the room that the entire profession ignores?

BY: Until a certain point, a lot of finance research work was descriptive. Insightful systematic observations were very helpful. Serious research works came later—and Chicago turned this into a science.

At the very beginning we were led by some intellectual giants that talked about agency problems, signaling problems, dividends, desirable capital structure, and so on. They gave us the theoretical framework to understand issues within the context of American corporate ownership. That’s fair; the academic market focused on what is researchable and on what was the hot topic in the U.S. at the time. The leading people, the founding fathers of modern research in financial economics, have done a great job. However, the rest of the world has been developing. There are interesting, relevant and helpful research questions outside. The upshot: I decided to go back to Asia; I want to know more there.

GR: The economics discipline was actually taught until the mid-20th century under the name “political economy”—only in the last 70-80 years “political” was dropped. Yet politics always played a huge role in all markets.

BY: These are the issues we discussed in the Canadian disease paper. It was published in 2000 but was first presented in ’97. Professor Luigi Zingales discussed the paper; he was very helpful.

GR: Isn’t it curious that it took a Canadian, a Hong Kong native, and an Italian to d

evelop an interest in the political influence that large conglomerates have in the marketplace?

BY: There were other people too, but, in my opinion, it clearly is the case that people from outside bring their experience and observations and match that together with the American research method. Diversity is great, and strong scientific method is not replaceable.

It was clear to us then that what happens is that you get rich, you expand into new areas, increase your control via pyramids, multiply, get to cover much of the economy, and then monopolize it.

You asked me before why it took so long for these issues to be properly researched. Well, one reason is that we do what the leaders do and follow them. The great majority of academics are behaving as such. It has something to do with our system. We need a high priest to give us the title, tenure, and so on. The other thing is that many of us in academia—and Chicago as well as other leading places are an exception—do research just to get tenure to make a living, not really because we care and have something to say. The exceptions show us the path.

GR: Perhaps people in academia were not fully focused or aware of these issues, but people in the business sector and politicians were definitely fully aware and engaged. They knew how the market works and the role of power and political power in the business. Even you, as a clerk for Chase—a clerk, not a CEO—were aware of this and how it works.

BY: My feeling is that we all have our own life experience. As long as we are doing social science, our life experience will affect us to some extent.

You get training and you long to be in the system. You follow the high priests (of academia). After a while, you may get lost.

Your education uneducated you, but there are some people who are very insistent. They will go back to their history. They’ll go back to it and say: “I really want to do something that matters, something that I feel deeply about.”

There was a Chicago professor, Sherwood Rowland—who won a Nobel Prize in Chemistry later—who described how CFCs destroy the ozone layer in the atmosphere. He worked on his research day and night and got home very late. I heard that once his wife asked him: “What are you trying to do?” “I’m trying to save the world,” he said. That’s really the right kind of attitude. We research because we care and want to say something meaningful.

GR: Would you agree that the notion that politics, regulation, legislation, market power and so on are determined by the structure of concentrated power can be in many cases the biggest elephant in the room?

BY: I agree. Concentrated economic power leads to concentrated political power. At the end, the two are mingled together and they create rules. Even in the elections. Even rigging elections.