Columbia professor Richard R. John explains the history of U.S. monopolies and why antimonopoly should not be conflated with antitrust.

For more than two centuries, distaste for monopolies has been an integral part of American society and political culture.((Arthur P. Dudden, “Antimonopolism, 1865–1890: The Historical Background and Intellectual Origins of the Antitrust Movement in the United States” (Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 1950).)) The antimonopoly tradition in the United States, which owes a great deal to the influence of Adam Smith, has informed the thinking of American revolutionaries such as Thomas Paine during the early republic. In many ways, it is older than the republic itself.

Richard R. John, a professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism who specializes in institutional and business history and in the political economy of communications in the United States, has spent a considerable portion of his career studying the history of monopoly and antimonopoly in the U.S., a largely understudied chapter in American history. In his 2010 book Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010), John traced the influence of political decision-making on the evolution of the telegraph and the telephone, by studying two government-backed private communication monopolies, Western Union and Bell/AT&T, and the political economies in which they developed and prospered.

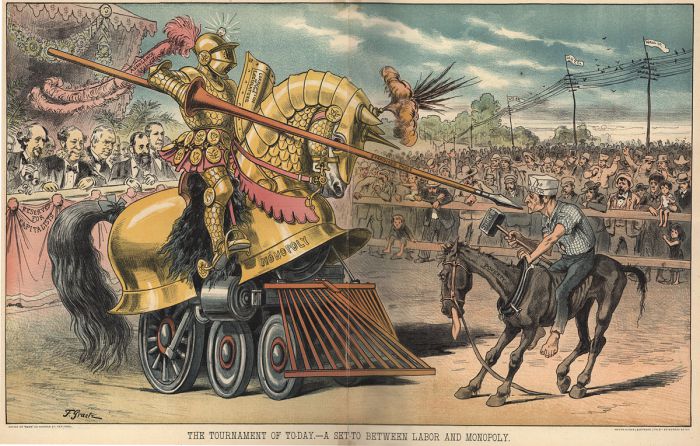

In a 2012 paper, John continued to explore the history of antimonopoly in America, revealing the extraordinary influence cartoonists had on public opinion regarding business norms, and the role business historians played in largely obscuring the legacy of the antimonopoly movement.

The importance of antimonopoly had been largely under-explored, according to John, for three main reasons. One is the conflation of antimonopoly with the enforcement of antitrust laws at the federal and state level, both of which, while important, are relatively recent phenomena. The second reason is a mistaken presumption that antimonopoly was primarily championed by farmers and laborers, outsiders to the urban, professional middle class, when in fact the movement was far more central and counted leading public figures like Louis Brandeis, Thurman Arnold, and Grover Cleveland among its ranks. The most effective proponents of antimonopoly, notes John, have often been “relatively well-placed.”

What happened to the American tradition of antimonopoly since the days of Brandeis? John is currently writing a book on the history of monopoly and antimonopoly in the U.S. In a conversation with ProMarket, John explained how it came to be that antimonopoly was largely cast aside in favor of antitrust, why it is wrong to conflate the two, and why he believes that the antimonopoly critique is coming back to prominence.

Q: You said the goal of your book project is to try to distinguish antimonopoly from antitrust. Can you explain?

The idea is to try to explain to contemporary Americans why so many of their predecessors found economic concentration so troubling, and what’s happened to that tradition. I think that antitrust is a much more limited dimension of antimonopoly than you would assume if you were looking at the historical literature, but it’s come to be identified with it.

Q: Can you explain what you see as the difference between the two? Why are they not synonymous?

We’ve got this tradition called antitrust, which became the platform for the development of this increasingly arcane body of law that solves a practical problem for businesses: what kind of conduct is legal, what kind of conduct is illegal? And that led to this elaboration of antitrust doctrine through the 20th century that exfoliated and developed all kinds of permutations that eventually collapsed intellectually in the 80s following the publication of anti-antitrust screeds such as Robert Bork’s 1978 Antirust Paradox.

If you conflate antimonopoly with antitrust, it’s a story of the late 19th century, with some successes in the early and mid 20th century and then collapse. So you’ve already left half of American history out. The tradition is much more important than that, and has much wider roots. We often don’t remember that the Boston Tea Party had an antimonopoly dimension. So too did Andrew Jackson’s protest against the Bank of the United States. The great concern among 19th century Americans was political power, concentrated political power. And that concern was not with economic performance, but with power, and the ways in which economic concentration can manipulate the political order.

Q: In your 2012 paper Robber Barons Redux: Antimonopoly Reconsidered, you explain that business historians such as Alfred J. Chandler Jr., whom you studied under during your PhD in Harvard, largely abandoned the critical examination of 19th century monopolists, the so-called “robber barons,” and started treating them as industrial statesmen and “organization builders” who became the beneficiaries of certain institutional arrangements, instead of critically examining the political economy in which they’ve come to dominate. Why did this shift occur?

Late-19th century business leaders were reviled. They got very little good press outside of the press that they had paid for. That doesn’t change until the First World War, when corporate public relations is invented, in large part to rebut these savage attacks on business. And the possibility of government ownership of the Bell System

is right at the center of that epochal transformation—which, among other achievements, legitimated managerial capitalism as a business ideology. Bell managers invented corporate public relations to help ensure that they got good press, and they succeeded.

By the 1930s you have the Great Depression, and a revival of the late 19th century antimonopoly critique. New Dealers revived and refashioned the much older proprietary capitalist critique of corporate capital. Proprietary capitalists did not believe that young men should work for large organizations. They thought it’s ‘unmanly,’ it’s demeaning–you are not autonomous, you are not your own man. And this critique was revived by the journalist Matthew Josephson in the late 1930s in the popular book called, The Robber Barons, in which he credits the origins of this critique of big business to populists, a characterization I think is largely mistaken. In my view the 20th century critique began with proprietary capitalists and was then picked up by populists.

The valorization of men like Rockefeller within the academy begins with a Columbia historian, Allan Nevins, who was trying in the 1930s to pioneer the archivally-based study of the country’s business leaders, which was hard to do, since businesses are notoriously secretive. After the Second World War Nevins got access to additional source materials, which he deployed to popularize a moral agenda that affirmed that business leaders were not robber barons but industrial statesmen who created the arsenal of democracy that enabled the United States to defeat the Nazis. Nevins’s biographies marked the culmination of the first phase of academic writing about business history in the United States.

Chandler fought in the Second World War and was predisposed to be sympathetic to big business, as a result of his upbringing in Wilmington, Delaware, where he knew many of the DuPonts. (He’s not descended from the DuPonts, even though his middle name is DuPont.) When he began to write history, he was uninterested in this robber baron/industrial statesman dichotomy. He aspired to rethink the history of big business by drawing on German social theory. The periodization of American business history that he devised focused on stages of economic development and the technological transformation of the external environment.

Chandler initiated a second phase in the study of American business history, which we now call the organizational synthesis. One of the corollaries of the organizational synthesis is a radical devaluation of politics—including, in particular, electoral politics. Electoral politics just didn’t matter that much to Chandler. The key transformations emerged from economy and technology, and elections were largely epiphenomenal.

The Democrats are in charge, the Republicans are in charge, it doesn’t matter much. A lot of younger [academic] stars don’t understand that. They don’t understand that the New Deal was epiphenomenal for historians like Chandler.

So that’s the second phase: relatively non-political, kind of flattened out, ‘we’re not going to have these debates about whether Rockefeller’s a good fellow, or a bad fellow. We’re just going to understand what made him successful, what large-scale corporations did.’ The entrepreneur for Chandler became more-or-less synonymous with the organization. In fact, Chandler read Schumpeter to imply that the entrepreneurial function was taken over by the multi-divisional firm, not the maverick.

Q: So this shift that you are talking about, there was a Schumpeterian influence to it? How did it hold up, in light of more recent economic upheavals?

Chandler read Schumpeter in a particular way. Yet I believe an even more direct influence on Chandler—he would contend he had been shaped mostly by Parsons, Weber, and Schumpeter—were the American progressives.

I read Chandler as an American progressive, in the sense that he wanted organized intelligence to coordinate critical economic functions. He certainly didn’t believe that managers can coordinate the entire economy, but he did believe that organizational capabilities matter, that big business can be creative and consequential, while that, at the margins there will always be mavericks. He just didn’t think the mavericks were as important as the large organizations. The mavericks’ ideas would be taken up by large organizations in those sectors of the economy in which there are technological and market-based reasons for large-scale enterprise to thrive.

The world doesn’t look that way now, and it stopped looking that way very soon after Chandler published his Pulitzer Prize-winning Visible Hand, the core of which focused on the period between 1880s and the 1920s, when his model most closely fit the facts.

After 1970s, there’s been a third way of thinking about enterprise, which has taken the form of a principled indictment of large-scale organizations. These critics presume that large organizations are ossified, that they do bad things, that they are uncreative, and that the springs of innovation come from the margins, outsiders, mavericks.

This revisionist tradition has been powerfully reinforced by the commercialization of the Internet in the 1990s. Today, for example, when we talk about entrepreneurship, we are more likely to be describing an 18-year-old geek in a garage who has come up with a new idea—and not the manager of a giant organization like General Motors.

This was not Chandler’s conception of entrepreneurship at all. If Chandler were alive, I am confident that he would point out, and I think quite rightly, that in X years–X being fewer than 10–the most successful startups in today’s digital economy have become very large organizations with names like Facebook, Google, Amazon, or Apple.

What we’ve done today by glorifying the garage-based entrepreneur, in effect, is to revive for the 21st century the 19th century proprietary, individualistic, anti-bureaucratic vision of what entrepreneurship is—at the cost of concealing and mystifying what’s actually happening.

Q: Mystify in what way? Happening in what way?

Well, because we assume that there’s nothing to worry about regarding Google or Facebook, since they didn’t get special legal privileges like the Bell System; and, as a result, we’re not even paying attention to the way that they behave. In fact, their behavior is not seen as a political question at all—a huge mistake.

When lawmakers dismantle

d the Bell System in the 1980s, it was obvious to anyone who’d studied the subject for 10 minutes that it was not technology and economics that kept the Bell System together, it was politics and culture.

I’m not making a moral evaluation here of what the lawmakers in the 1980s did. The Bell System was a monopoly—but it was not the kind of monopoly that we need to be worrying about today.

Many firms today have gained control over certain sectors of the economy, without being in any obvious way the beneficiary of a legally mandated special privilege. When I talk to my economist friends, they say: “the only kind of monopoly we need to worry about is a monopoly that’s the beneficiary of a special privilege granted by a legislature.” Well, nonsense. That’s much too narrow a definition of monopoly to make sense of the problems and benefits that economic consolidation can bring.

Q: If I understand your point correctly, you’re saying that we’re looking in all the wrong places? We’re looking for benefits, and not the concentration of political or economic power?

Exactly. Because monopolies bring with them all kinds of consequences that extend well beyond innovations in supply chain management. They shape politics. They shape the whole conception of what the national interest is. And we don’t have a good understanding of these kinds of consequences.

Q: What happened to the antimonopoly sentiment that was once so common in America? Has it disappeared completely?

I wouldn’t say it completely disappeared, but the reason we think it disappeared is because we associate the tradition with antitrust enforcement, and there had been a lot of failures in antitrust enforcement. I think that’s a big mistake—to conflate antimonopoly with antitrust.

Q: In Robber Barons Redux, you mention that antimonopolists could once be found “all across the political spectrum.” In recent decades, however, antimonopoly came to be strongly identified with the left. Is antimonopoly a left/right issue?

I don’t think so. In fact, I believe it would be a major contribution to public discourse if we could get the idea of monopoly out of this particular political pigeonhole. The idea that the government is conspiring with business to promote certain undesirable social policies or certain dangerous ideas—that is, the idea that we are confronted with a specter that haunts the country—is not confined to the left. For this reason, I’m not so quick to see antimonopoly as a left/right issue.

But within the academic community, particularly among economists, it is. If you read Robert Bork’s The Antitrust Paradox, the extent to which he associates antitrust with insidious, left-wing radical demagoguery is astonishing. That was not a position that would have made sense in the 1930s, in the ’40s, or the ’50s.

The marginalization of monopoly as a focus of inquiry within economics is an important issue. Monopoly was a classic issue for economists. Hayek was very troubled by monopoly. Its marginalization has something to do with the over-reliance on quantification as an economic tool, something to do with the assumption that economics is value-free, something to do with the critique of any kind of regulatory intervention, as well as the assumption that somehow, markets will solve all problems on their own.

The neglect of our long and distinguished antimonopoly tradition among so many economists today is striking, and in many ways unaccountable. To claim that because regulatory agencies can be captured, therefore we should not have regulatory agencies, is a bizarre syllogism, yet it’s one that has got tremendous purchase among economists—and on the Right.

Any history of antimonopoly has to underscore the extent to which the antimonopoly tradition was important long before it became the prerogative of economists, which has only occurred in the late 20th century. In the 19th century it was everybody’s business. Antimonopoly today has come to be treated by the Left and the Right as a highly technical matter that you could measure with certain quantitative techniques. If you’ve done X, then you’re a monopoly. If you’ve done Y, then you’re not. But that sort of misses the point.

Q: You are currently writing a book about the history of monopoly and antimonopoly in the U.S., can you share some of your findings?

Of the three main themes in my project, the first is that monopoly is a moral and political question, not only, or even primarily, an economic question.

The second is that the most effective critics of monopoly are often closer to the center of the economy than we have assumed. They are typically rivals, patrons, suppliers, or would-be entrants. They are not only or even primarily relatively marginal outsiders such as small-scale farmers or industrial workers. That it, it was not only the groups on the periphery that have led the charge, however undeniably important they often have been.

The third theme is that monopoly and antimonopoly have to be understood from the beginning in an international political economic context.

We’ve lost sight of the problems that monopoly—that is, concentrated economic power–poses in a democracy, because we’ve so narrowed the grounds on which the issues are being debated.

Q: You argue that antimonopoly was never exclusively pushed by outsider groups like farmers and workers, that it was also championed by “well-born patricians” like Charles Francis Adams, Jr., along with merchants, entrepreneurs, and crusading reformers. As you mentioned yourself, this somewhat goes against the common portrayal of the antimonopoly movement and its champions.

Until the 1880s antimonopoly was understood to be a central dimension of American civic identity. From the 1880s to the 1910s, you have a transformation of that presumption into economic policy, which we call antitrust.

This shift would be easier to understand if the historians of the past few generations had keep their attention on the center rather than the periphery. But for good and understandable reasons, many historians lost interest in the political economy, and focused instead on marginalized groups. And if you focus on marginalized groups, then you will naturally assume that all the important ideas originated with those marginalized groups. And that led to this very one-dimensional understanding of what the antimonopoly tradition has been, or can be.

There’s currently no full scale overview of the antimonopoly tradition in the United States. There are monographs on certain selected topics, but it’s not been considered an important subject in its own right.

Writing in the early 1980s, one distinguished intellectual historian praised the anti-monopoly tradition as a major contributor to progressivism, only to dismiss it—wrongly in my view– because it wasn’t international. In part for this reason, antimonopoly is often dismissed by historians as a parochial American concern that has no relationship with the wider world. In fact, antimonopoly has always linked the United States with the wider world. We just haven’t realized it.

Q: Can you elaborate?

Consider the East India Company, the Bank of United States, and Standard Oil—these were all enterprises that from the moment of their inception had been operating in global markets. We need to overcome this parochial view of the United States as an entity that was distinct from Europe and the wider world until the Second World War, This is a very common way in which American history has until very recently been taught and understood by the public.

Q: What did differentiate the antimonopoly movement in the U.S.? What made it successful?

That’s an interesting question. One measure of success is the extent to which the idea that economic power can be politically dangerous is accepted. And that idea was accepted by everyone up through the 1880s. And then in the 1880s, an influential group of proprietary capitalists—including many powerful wholesalers–suddenly realized that they were likely to be the losers in the emerging economy order. These wholesalers joined with influential shippers to promote a new body of law that would lead to the Sherman Act of 1890—and, with it, the modern tradition of antitrust enforcement.

After the Second World War, Americans ceased to regard antimonopoly as an important issue domestically. That is to say, public figures ceased to regard it as important domestically as an issue that could galvanize the public. Somewhat surprisingly, it was at precisely this time that there emerged a burst of interest within the foreign policy establishment in exporting antitrust overseas, precisely for reasons the Founders would have understood: because if you don’t have antimonopoly, then you’re going to have a recurrence of fascism. And, at the risk of oversimplification, that’s why we reorganized the economies of Germany and Japan. And we did it in a quite systematic way. In principle, if not necessarily in all its details, Hayek would have approved.

Q: You finish your 2012 paper with a prediction, or premonition, that the antimonopoly critique is coming back. Why? Do you see a similarity between the current U.S. economy and period where antimonopoly sentiments were common?

In Network Nation, I wrote about the political economy of the telegraph and the telephone. The telegraph network emerged in a political economy that had been shaped by antimonopoly norms that encouraged open access to the market–emboldening telegraph managers to pursue a particular business strategy. Political structure shaped business strategy. Antimonopoly norms fostered a business strategy that was narrowly focused on producing services for an exclusive clientele—the nineteenth-century equivalent of the 1 percent. Antimonopoly, to be sure, had fostered certain innovations—including the telephone—but it also discouraged telegraph managers from expanding their mandate to serve the many as well as the few.

With Bell, it was completely different. In the nation’s largest cities, which was where the telephone business first flourished, there was never a presumption that access to the telephone market would be open. The market was always tightly regulated by municipal authorities, and as a result telephone managers were always concerned about corruption and extortion. The Chicago city council was particularly notorious for the ingenuity with which its aldermen shook down operating companies to line their pockets. To extricate themselves from those localistic political pressures, entrepreneurial operating company managers devised a very broad vision of a socially responsible corporation that performed a public service in return for regulatory oversight. Instead of serving the 1 percent, like the telegraph companies, these operating companies would provide cheap and convenient local telephone service for the people. This strategy succeeded by around 1900—making the telephone the first electrical communications medium to be accessible to the many as well as the few. Government regulation was not the enemy of innovation—but its catalyst.

Since the 1970s, belief in the the concept of the corporation having a social responsibility to stakeholders that included the communities in which they were located has diminished. Now that we have come to live in a world in which fewer and fewer public figures are willing to hold large-scale enterprises accountable as socially responsible institutions, then it seems to me that we have returned to the world of antimonopoly. But we’ve made this shift, not from a world that had been dominated by proprietary capital—as was the case in the late 19th century—but from a world in which corporate capital has now become almost completely evacuated of any larger moral or political objective. I think that’s worrisome. I think that’s why antimonopoly is back.

Q: Which brings us again to the issue of left and right, both sides of the political spectrum, and whether they can unite in critique of monopolies.

Agreed. I do not see antimonopoly as a classic left/right issue. It is instead an issue about fundamental core values in which there has been historically a large measure of consensus. Since the founding of the republic, there has existed in the United States a set of norms, rooted in everyday experience and Anglo-American political theory, which are suspicious of concentrated power. And once it becomes obvious that large-scale organizations are concentrated, unregulated, and not necessarily working in the best interests of communities, the nation, or the world, then, if we are true to our heritage, these organizations will, once again, find themselves the target of sustained political attack.