While it is still too early to draw any decisive conclusions regarding the role money played during this election cycle, some trends can already be observed.

The 2016 election cycle might be the most expensive in U.S. history. The Center for Responsive Politics estimated this week that total election spending by candidates, parties, and outside groups will reach at least $6.9 billion by the end of the current election cycle, making it at least $308 million more expensive than the 2012 cycle after adjusting for inflation. So far, according to the center’s data, presidential candidates have raised $1.3 billion, with super PACs raising $594 million more.

But this election cycle has been characterized not just by a spike in the amount of money spent by candidates, parties and the outside groups supporting them, but also by the growing influence of big donors and a historic rise in the concentration of political donations. Since it was first launched in March, the Stigler Center’s Campaign Financing Capture Index, which tracks the attempts of large political contributors to affect public policy, showed rapid growth in contributions from big donors, compared to previous election cycles.((“Campaign Financing Capture Index: Historical Comparison Shows the Extent of Growth in Political Contributions From Big Donors.” ProMarket, May 2.))

The Center for Responsive Politics’ analysis confirms this conclusion: last week, it estimated nearly 11.9 percent of the funds raised so far during this election cycle came from just 100 families. In the entire 2012 cycle, the top 100 donor families donated 5.6 percent of funds raised.

With the election only one day away, it is still too early to draw any decisive conclusions regarding the role money played during this election cycle. With more money coming in new and inventive ways, it may also take some time before the full cost of the 2016 cycle is tallied. Yet there are some trends that can already be observed:

The rising influence of big donors: 2012 was the “testing ground”

Both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump regularly tout the contributions they get from small donors. During the Democratic primary, Bernie Sanders famously raised more than 50 percent of his contributions from small donors. Yet the 2016 cycle has mostly been characterized by a rapid increase in the concentration of political fundraising among a set of very wealthy donors. According to a recent analysis by The Wall Street Journal, two dozen billionaires have spent $88 million on the 2016 presidential campaign, with the vast majority of these funds going to Hillary Clinton and her supporting super PACs. According to the Washington Post, of the $1.1 billion raised by super PACS through the end of August, nearly 20 percent came from just ten mega-donors and their spouses.

When it comes to big donors in 2016, the scale tilts heavily toward Clinton. Despite attempts to woo big donors alienated by the GOP nominee, the Trump campaign has relied mostly on small, digital, and mail-in donations. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, Trump has raised less money than any general election candidate since 2000, with the money he loaned his campaign accounting for more than 25 percent of the $169 million he has raised as of September 30. Trump is also the first GOP nominee in many years to not receive the backing of any Fortune 100 CEO.

Clinton, on the other hand, has focused much of her fundraising efforts on pursuing big donors. According to The Wall Street Journal, she has 19 billionaires to Trump’s four. An analysis by The Washington Post found that more than a fifth of the $1 billion donated to support Clinton was given by “just 100 wealthy individuals and labor unions—many with a long history of contributing to the Clintons.”

Our own research at the Stigler Center has also shown that Clinton is much more reliant than Trump on big donors,((“Campaign Financing Capture Index: Donald Trump Keeps Losing Affection from Big Donors, While Clinton Maintains It.” ProMarket, October 5.)) and that this concentration isn’t the result of a few mega-donors: in general, Hillary Clinton attracts wealthier donors than Trump.((Tania Diaz Bazan, “Wealthier Donors Prefer Hillary Clinton.” ProMarket, November 4.)) The median home price of Clinton’s supporters is $639,796 while Trump’s donors’ median home price is $474,427. Hillary Clinton received nearly 100 percent of contributions made by academics in top universities,((Tania Diaz Bazan, “Donation Preferences: Republicans Outnumbered in Academia.” ProMarket, October 7.)) and overwhelming support from the banking industry: 98 percent of the contributions raised by workers at financial institutions like Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase, and Citi went to Clinton’s campaign.((Tania Diaz Bazan, “Employees of Large Companies Favor Hillary Clinton.” ProMarket, October 20.))

This last statistic may seem surprising, given Clinton’s promises to be tough on Wall Street. Yet our research has shown that in instances in which the probability of a Clinton presidency increased during the last month, financial and pharmaceutical stocks went up, suggesting that the market may not put much trust in Clinton’s promises and sees her presidency as a boon to these industries.((Andrea Hamaui, “Finance and Healthcare Bound to Gain from Clinton’s Presidency.” ProMarket, November 6.))

In fact, one of the many ironies of the 2016 election cycle is that the candidate most critical of big money’s influence on politics is also its biggest beneficiary. Clinton, who has promised to overturn Citizens United if elected, and her main super PAC Priorities USA Action have raised nearly $700 million through late October, more than twice as much as Trump and his supporters.

While Clinton has a solid advantage over Trump in nearly every category of fundraising, her lead becomes overwhelming when it comes to big donors: nearly a third of her contributions come from donors who contributed more than $100,000. Clinton has the backing of nine out of this election cycle’s biggest donors, and 85 percent of the contributions given by donors who gave $1 million or more. Clinton and the Democratic party, along with the PACS, super PACs, JFCs, and groups supporting her are estimated to have raised well over $1 billion, on par with the $1.1 billion raised by President Obama and his backers in 2012. Trump, on the other hand, stands little chance of raising $1 billion, as Mitt Romney did.

This election has also been marked by a remarkable rise in public awareness to the flaws in the campaign financing system, with candidates from both left and right criticizing the influence of big donors. As early as December, a Stigler Center survey showed that 57 percent of Americans believe that “candidates who take money from big businesses, unions and special interest groups are under their control.((“Stigler Center Survey Reveals: Majority of Americans Concerned About the Influence of Campaign Donors on Candidates.” ProMarket, March 9.))

While Citizens United, the 2010 Supreme Court ruling that overturned the limits on corporate political spending, is often portrayed as the main catalyst for the rise in political spending, it is not the direct culprit. The rise of super PACs, for instance, stems much more from the 2010 decision by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals on SpeechNow v. FEC, which according to Harvard Law School professor Laurence Tribe “gave birth to the super PAC takeover of American politics.”

“I think people make the mistake of saying Citizens United all the time—Citizens United is a metaphor,” says Richard Briffault, the Joseph P. Chamberlain Professor of Legislation and Vice Dean at Columbia Law School, in an interview with ProMarket.

According to Briffault, the rise in political spending in 2016 has more to do with the 2014 Supreme Court decision in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission, which removed the cap on the aggregate amount individuals can give to federal candidates, previously imposed by the Federal Election Campaign Act (“FECA”).

In fact, despite the Citizens United ruling, most of the surge in outside spending since has come from wealthy individuals, not corporations and unions. According to a study released this month by Conference Board’s Committee for Economic Development, individuals account for roughly 80 percent of super PAC donations since the beginning of the election cycle through late July. Companies and unions contributed just 8 percent and 1.9 percent, respectively, during this period.

“I am not sure the 2016 election is unique. I think we’re in a pattern that developed in 2012 and 2014, and the pattern doesn’t actually have all that much to do with Citizens United, which technically is about corporate spending in federal elections. In fact, you see a lot of wealthy individual spending in federal elections and not a lot of corporate spending. The main form which corporate participation takes is not-for-profits. Most of the big spenders are technically nonprofits, serving as conduits for corporate money, business money, labor money, and individuals,” says Briffault.

The main impact of Citizens United, Harvard Law School professor John Coates told ProMarket in May, was that is served as a signal delivered by the Supreme Court to politicians and donors that “restrictions on campaign

finance were suspect.” Prior to Citizens United, “Republicans had been very much in favor of disclosure regulations, as a way of saying ‘we’re not in favor of more restrictions, we’re only in favor of disclosure.’ But after the case they sort of won the battle on restrictions, so they now fight disclosure too,” he said.

One major development from previous elections, experts say, is the sophistication by which political contributions are channeled post Citizens United, in some cases in violation of existing laws and regulations. “In the post Citizens United world, we have two campaign finance systems: the regulated system, that covers candidates, parties, and traditional PACs, and the unregulated system of so-called ‘independent’ spending,” says Catherine Kelley, director of the State & Local Reform Program at the Campaign Legal Center, a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that advocates for stricter enforcement of campaign finance laws, in an interview with ProMarket.

“People really know how to do that now: 2012 was the testing ground,” she adds.

The rise of outside groups

Another trend that became more pronounced during this cycle is the surge in spending by outside groups. Outside groups have spent $1.4 billion so far in this election, up from $787 million in 2012. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, outside groups account for 26 percent of all election spending so far in 2016, compared with 16 percent at the same point in 2012. Much of this spending has gone to Congressional races and statewide races for executive office, where outside groups “overwhelmingly poured larger sums,” spending $93.7 million more than they did in 2012.

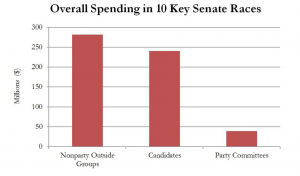

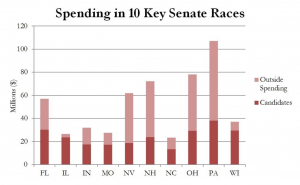

Outside of the presidential election, a report released this week by New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice finds that outside spending is now pouring into key Senate races at a “record pace,” to the point that in several highly competitive races, outside groups are outspending the candidates and their parties. $557 million have been spent so far in key Senate races in states like Nevada, according to the report, with 51 percent ($282 million) coming from outside groups.

“Generally the trend we’ve seen since Citizens United was decided is that more of the spending goes through these outside groups that have no contribution limits,” says Ian Vandewalker, author of the report and counsel for the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program.

Unlike the presidential election, in these Senate races Republicans are outspending Democrats: the report finds that nearly 60 percent of the money spent so far in these key Senate races has gone to either support Republican candidates or attack their Democratic rivals. Dark money, the report finds, favors the GOP candidates in these races six-to-one.

The most prominent dark money group in this election cycle is One Nation, a 501(c)(4) nonprofit with ties to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell that is reportedly backed by prominent Republican donors, among them, according to a Guardian report, mega-donor Sheldon Adelson. The group has spent $31 million so far, which, according to the Brennan report, accounts for 35 percent of all the dark money spending it found.

It is difficult to decipher the true scale of dark money spending in this election. “There are two kinds of dark money: one is money that is campaign-related, but it’s being spent by groups that are primarily not campaign-related, so they don’t have to register as political committees, and therefore don’t have to disclose their donors. We have good numbers on that, because those groups report their spending. What’s a little trickier is groups that claim their spending is not electoral at all, and therefore don’t have to disclose their spending or their donors. That’s harder to know,” says Briffault.

The 2016 election cycle has a dark money legacy that could prove to be influential in future election cycles: in the Republican primary, Senator Marco Rubio was supported by a 501(c)(4) organization called Conservative Solutions Project. The nonprofit raised $13.8 million shortly after Rubio joined the race, including $13.5 million from a single anonymous donor whose identity was never discovered. According to Politico, the organization spent more than $10 million on TV ads, mailers and research supporting Rubio’s candidacy.

Nevertheless, the role that dark money is playing during the 2016 election seems to be smaller than analysts had previously thought. “The secret spending is still there, but it hasn’t expanded to the degree some people thought it would, largely because super PAC money has grown much more,” says Vandewalker. “With a super PAC you can spend 100 percent of its revenue, while if you set up one of these nonprofits, the IRS in theory won’t let you spend all your money on politics.”

According to Briffault, “Dark money is definitely up, but as a percentage of the total amount spent, I’d be surprised if it’s 10 percent. Most of the money that is being spent in the presidential election is disclosed money, raised by candidates, parties, and super PACs.”

With “no cop on the beat,” the use of super PACs has become more “brazen”

Candidates are forbidden by law from coordinating with the super PACs supporting them. The logic b

ehind this rule is simple: while it could be argued that unlimited contributions from individuals or organizations that work completely independently from a candidate’s campaign pose little to no risk of influence, it’s hard to argue the same when there is direct coordination. Experts, however, claim the law is not being enforced.

In October, the Campaign Legal Center filed complaints with the Federal Election Commission against the Trump and Clinton campaigns for illegal coordination with several super PACs. Several former Trump campaign officials, it alleged, formed super PACs immediately after leaving the campaign, in violation of FEC rules, and continue to work closely with their former colleagues. Trump’s campaign manager Kellyanne Conway, is the former president of a super PAC now supporting Trump, and was hired, according to the complaint, “at the behest” of the super PAC’s chair.

The Clinton campaign, meanwhile, is coordinating directly with the Clinton-supporting super PAC Correct the Record, according to the complaint. Correct the Record does this openly, relying on a 2006 FEC regulation that allows individuals to disseminate free online content (such as blogging) in coordination with campaigns, to argue that this is legal as long as the super PAC doesn’t run paid advertising. “Because Correct the Record is effectively an arm of the Clinton campaign, million-dollar-plus contributions to the super PAC are indistinguishable from contributions directly to Clinton–and pose the same risk of corruption,” the organization argued.

In previous election cycles, candidates have often tested the limits of what’s possible under the existing coordination and disclosure rules, using various loopholes that allowed them to work with super PACs supporting their candidacy. The 2016 election, however, has been marked by a much bolder spirit, with some candidates blatantly disregarding the rules.

“Pretty much every candidate in this cycle has a super PAC, and the ways campaigns are using them as another arm of their campaign has become more brazen,” Kelley says. “On many fronts, candidates are pushing the boundaries.”

A telling case, Kelley says, was the campaign of former HP CEO Carly Fiorina, who had reportedly been working closely with a super PAC supporting her before she dropped out of the GOP primary. “Carly Fiorina’s super PAC was the most interesting, in that her super PAC was doing most of the ground game organization, organizing activities and events, and she would just show up,” says Kelley.

Much of this emboldening stems from the inaction of the FEC, which has been deadlocked in recent years. “Everybody knows the FEC is not going to do anything, and they are emboldened in the way they can use their super PACs. I think there is a sense of ‘we might as well push the envelope.’” adds Kelley.

The dysfunction of the FEC is a foregone conclusion at this stage, to the point that in 2015 its then-chairwoman, Ann Ravel, famously filed a petition against her own agency and said that she had given up hope of regulation of abuses during the 2016 election, telling The New York Times that “the likelihood of the laws being enforced is slim.”

“There is no cop on the beat, no one is regulating the system. I definitely think people are getting bolder and bolder—every year someone tries something new to push it a little farther,” says Vandewalker. He adds: “There are basic things that the FEC does regulate. But when it comes to these border cases, when someone is pushing the envelope or being aggressive, those are the cases where the FEC is deadlocked.”

“The FEC is not set up to be very effective, but there were times when the FEC actually enforced the law,” says Briffault. “The current system is dysfunctional, but there was a time when you didn’t have so many ties, and there was much greater willingness to enforce the law. Republican members are actually quite hostile to the law, and are therefore not particularly interesting in enforcing it.”

Vandewalker, however, warns of “laying all the fault at the feet of the FEC.” He adds: “Congress needs to enact stronger legislation, the Supreme Court needs to stop striking down common sense rules. The IRS is so gun-shy after the way it got attacked following the 2013 political targeting scandal that dark money groups are confident the IRS is not going to come after them. The problem has to do with multiple actors within the system not helping or making things worse.”

Despite promises, federal reform is unlikely. But states might be the key

Hillary Clinton, who according to polls is most likely to win the election, has been outspoken about her intentions to repeal Citizens United if she is election. Clinton has also made campaign finance reform one of her signature issues, promising to “end the stranglehold that the wealthy and special interests have on so much of our government.”

Can a candidate who owes their rise to the current campaign finance system be able to lead a reform that drastically alters a system to which they owe their power, especially if they intend to run for reelection? Clinton adamantly insists that is her intention, but nevertheless, there are significant doubts as to whether she will be able to pass meaningful reform.

“There’s no reason we won’t see more of the same. At the national level, even if the presidency changes, and even if the Senate changes, it’s not clear that the House will change and it’s not clear if Congress will be willing to pass anything,” says Briffault.

But as Doron Navot argued in a ProMarket post last week, the flaws in America’s campaign financing system run much deeper than a mere lack of will political will. The experience of the campaign finance regulation in the last four decades, he wrote, has shown that the “donor class” is often able to find ways to “turn wild,” and has usually enjoyed the support of the Supreme Court in doing so.((Doron Navot, “Academic Literature Shows: The Problems with Regulating Campaign Finance Are Deeper Than Mere Lack of Political Will.” ProMarket, November 3.))

The Campaign Legal

Center, according to Kelley, is currently focusing on state and local efforts to regulate campaign finance. On November 8, voters in four states will decide on a number of statewide measures to reform the campaign finance system. In California, voters will vote on proposed limits to campaign contributions and on Proposition 59, which calls on elected officials to call for a repeal of Citizens United, and in South Dakota, voters will decide on Initiated Measure-22 (also known as the Anti-Corruption Act) that aims to place restrictions on political contributions from parties and PACs and create a public financing system for elections. Similar measures, including a referendum on the overturn of Citizens United, will be on the ballot in Washington State and Missouri.

On the federal level, says Briffault, three things are “in the realm of the possible.” One is a “robust public funding program,” which he says will “empower small donors and provide a mechanism by which small donors at least to some extent can offset the effect of big money, thereby increasing competition in the system.” Another possible reform will be a revision of disclosure rules, in favor of new rules “designed to take into account the fact that the real problem today is not the disclosure of spending but the disclosure of donors to dark money organizations.”

The second one, he says, is “probably the easiest to do, since there’s no constitutional issue.” The third needed change, according to Briffault, is a more effective policing of coordination rules. “These are not wild changes,” he says. Nevertheless, he notes, “in the near term, we’re not likely to see much of anything at the federal level.”

“We never rule out hope that something will happen on the federal level, but we’re realistic in the sense that it’s much easier to get things done on the level of states and cities,” says Kelley. “There is greater opportunity there right now.”