The first installment in a four-part series about the history of antitrust language in American political discourse: politicians from the Right and the Left are trying to bring back focus to the role of antitrust, bigness and concentration in the U.S. economy. A close analysis of the language in both parties’ platforms over the past 140 years by ProMarket may suggest that it’s long overdue.

“Large corporations have concentrated their control over markets to a greater degree than Americans have seen in decades–further evidence that the deck is stacked in for those at the top. Democrats will take steps to stop corporate concentration in any industry where it’s unfairly limiting competition. We will make competition policy and antitrust stronger and more responsive to our economy today, enhance the antitrust enforcement arms of the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and encourage other agencies to police anticompetitive practices in their areas of jurisdiction.”

The above paragraph was added, without much media attention, to one of the latest drafts of the Democratic Party Platform–and made it into the final draft. It was preceded by a speech given by Senator Elizabeth Warren in June with the same message.

The platform continues: “We support the historic purpose of the antitrust laws to protect competition and prevent excessively consolidated economic and political power, which can be corrosive to a healthy democracy. We support reinvigorating DOJ and FTC enforcement of antitrust laws to prevent abusive behavior by dominant companies, and protecting the public interest against abusive, discriminatory, and unfair methods of commerce. We support President Obama’s recent Executive Order, directing all agencies to identify specific actions they can take in their areas of jurisdiction to detect anticompetitive practices–such as tying arrangements, price fixing, and exclusionary conduct–and refer practices that appear to violate federal antitrust law to the DOJ and FTC.”

Barry Lynn, the director of the Open Markets program at New America, who authored a book on monopolization((Barry C. Lynn, “Cornered: The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of Destruction.” (Wiley, 2010).)) and is a key player in reinvigorating the anti-monopoly discourse in the U.S.,((Zach Carter, “Meet The Man Who Is Changing Washington’s Ideas About Corporate Power.” Huffington Post, September 2016.)) believes that the Obama administration did very little to stop consolidation and concentration in U.S. industries in the last eight years. “That speech,” he said during a recent conversation with ProMarket, “was extremely important. It was the most important statement by a major political figure in the U.S. on political economics in 80 years.” Lynn believes that Senator Warren’s speech and the new language in the platform may represent a shift in the Democratic Party’s stance on antitrust.

According to Lynn, “Warren has created a space where Republicans can get on board. She often works with Republicans on financial reform issues and she’s got a bill on too-big-to-fail she’s co-sponsoring with Senator John McCain. I’m sure that she was thinking about that while putting this speech together–the potential to work with Republicans on these issues.”

While most of the language on economic issues in the last election cycle focused on trade agreements, the new discourse on monopoly is focused on increasing competition, not on protecting U.S. manufacturing from international trade.

Interestingly, although the U.S. prides itself as the most pro-market, capitalistic democracy in the world, language on the importance of competition and antitrust did not take a significant, if any, part in political discourse in the last thirty years.

Many politicians and public intellectuals in the U.S., especially from the late 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, were concerned with the concentration of economic power. But Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis (1856-1941) was probably the most influential of them. Brandeis, arguably one of the most important justices and intellectuals in US history, was known as the “people’s lawyer.” He devoted a significant part of his life and career to fighting concentration, monopolies, and the political power of trusts that controlled large swaths of the U.S. economy in the beginning of the 20th century. In his writings as a lawyer, public intellectual, advisor to President Woodrow Wilson, and as a judge, he relentlessly attacked the “curse” of trusts that stifled competition and corrupted politics.

In April, President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers released a brief that claimed, for the first time in many years, that competition is weakening in most American industries. Nobel Prize laureates like Joseph Stiglitz and Paul Krugman have started to write more about the role of concentration and lack of competition in the U.S. economy as a source of inequality and stagnant growth. Now it seems that these ideas are starting to enter political discourse.

Two weeks ago, The Economist, arguably the most influential business publication and a strong supporter of free markets, wrote that “the age of entrepreneurialism that started in the early 1980s is giving way to a new age of corporatism. This has been particularly true in the world’s most advanced economy, America, and in the world’s most knowledge-intensive industries. Big companies have been getting bigger and putting down deeper roots. In the technology industry a handful of companies have grown into giants in a couple of decades and are now making sure they stay on top, hoovering up talent, buying up patents and investing in research. At the same time the rate of small-business creation is at its lowest level since the 1970s.”

The article also points to a Gallup survey in which almost 40 percent of respondents said they had very little or no faith in big business, while about 20 percent said they had a great deal or quite a lot of faith in big business. At the turn of the previous decade the two camps were equal at about 25 percent.

Language and declarations in political parties’ platforms are non-binding and can be tossed out the window after the election–especially when the proposed policy involves taking on powerful interests. In the case of antitrust, the special interest groups are not only some of the most powerful economic players in the U.S., but also the biggest donors and lobbyists (see ProMarket’s coverage)

Yet language and ideas that start as campaign and political tools may signal the sentiments amongst the parties’ grassroots electorate, and can create a dynamic that eventually, in the long run, will make its way into policy. That is why we at ProMarket decided to examine the history of anti-monopoly language and ideas in the platforms of the Republican and Democratic parties over the last 140 years. We analyzed the texts of both parties’ platforms for each election cycle from 1876 to 2016: 140 years, 36 election cycles, and 72 platforms altogether.

This analysis reveals the changing attitudes of both parties regarding issues like monopolies, trusts, antitrust, regulation, and deregulation over time. In some cases, the changing language preceded actual legislation and in some cases followed it. But the issues were indeed discussed.

We will share our findings in four installments. The first, presented below, is an overview, starting with the current state and then moving to the main findings. In the next installments we will examine in greater detail the results and the actual platforms.

A revival of antitrust?

On June 29, Senator Elizabeth Warren gave the keynote address at New America’s Open Markets Program event in Washington, DC.

The 3,500-word speech was focused on the economy. “I love markets! Strong, healthy markets are the key to a strong, healthy America,” Warren said in the beginning of her speech.

While choosing to focus on the economy is not surprising, Warren’s choice of words was, as it reflected her deeper focus: the function and structure of markets.

Warren’s speech mentioned the word “competition” in all its derivatives 49 times, “concentration” in all its derivatives 26 times, the word “antitrust” 15 times, the word “monopoly” and its derivatives 7 times, and “too big to fail” 3 times.

The context leaves no space for misinterpretation: “But today, in America, competition is dying,” “the truth is pretty basic—markets need competition now,” “strong Executive leadership could revive antitrust enforcement in this country,” and “consolidation and concentration are on the rise in sector after sector.”

And Warren named names: Apple, Google, and the banking sector are each mentioned 7 times in her speech, Amazon is mentioned 6 times, and the airline industry and its biggest companies 8 times.

A week after Warren’s speech, Time asked whether antitrust discourse is coming back. Haley Sweetland wrote that this may not be an isolated case of politicians shifting focus.((Haley Sweetland Edwards, “Why Bigness Became a Bipartisan Cause on Capitol Hill.” Time, July 2016.)) Citing a Marketplace and Edison Research poll that found that 70.9 percent of Americans think “the economic system in the U.S. is rigged in favor of certain groups,”((Marketplace-Edison Research poll, May 2016.)) Edwards wrote that “… in the last few months, a growing number of both Republican and Democratic lawmakers have begun to suggest another explanation for this widespread feeling of malaise: Bigness.”

On June 21, a hearing took place at the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Competition Policy, and Consumer Rights regarding “bipartisan legislation to address rising prescription drug prices.” In a statement, subcommittee chairman Mike Lee (R-UT), wrote that “unfortunately complex regulatory environments are being abused by some firms to avoid competition and keep prices high.”((Senator Mike Lee press release, June 2016.)) A week earlier, Lee, Senators Chuck Grassley (R-IA), Patrick Leahy (D-VT), and Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) introduced the Creating and Restoring Equal Access to Equivalent Samples (CREATES) Act to “deter pharmaceutical companies from blocking cheaper generic alternatives from entering the marketplace.” In March, Edwards notes, Lee voiced similar concerns in the subcommittee’s hearing, its first meeting in three years.

Also, in March, Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT), asked FTC Chairwoman Edith Ramirez whether the U.S. was investigating European regulators’ concerns about Google’s Android operating system for mobile devices.

Similar ideas were expressed in more detail in Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) May issue brief, titled “Benefits of Competition and Indicators of Market Power.” “Several indicators suggest,” the document says, “that competition may be decreasing in many economic sectors, including the decades-long decline in new business formation and increases in industry-specific measures of concentration.”((Council of Economic Advisers Issue Brief, “Benefits of Competition and Indicators of Market Power.” (May, 2016).)) (We at ProMarket have discussed this brief in detail here.)

Does all of this constitute a shift in the way American politicians view markets, competition, and regulation? When did the structure of markets enter the political mainstream? How did Democratic and Republican market rhetoric evolve over time? When and where did Democratic and Republican views conflict?

In order to try and answer these questions we analyzed both parties’ platforms over 140 years, using the University of California, Santa Barbara’s “The American Presidency Project” archive.((The American Presidency Project))

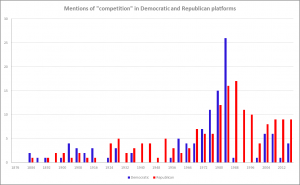

We searched the platforms for mentions of words such as “monopoly,” “trust” (in the sense of powerful business groups), “antitrust,” and “competition.” Charting their occurrences over the 36 presidential election cycles helped in analyzing the discussion over time. The results will be presented in detail further in the series.

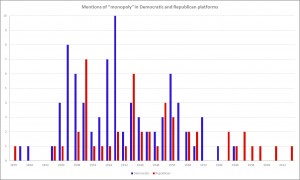

Monopolies

Monopolies appeared very early in both parties’ platforms: the Republican platform mentioned “monopolies” in 1876 and the Democratic platform mentioned the same word in 1880. Both were single mentions.

Monopolies became more apparent at the turn of the 20th century, when both parties fought against the trusts that had considerable influence over their industries. While The Sherman Antitrust Act, passed by Congress in 1890, did not seem to follow much discussion in any of the two major parties’ platforms, the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, which was signed into law during Democrat Woodrow Wilson’s presidency, was preceded by many mentions of monopolies.

In 1933, following the Great Depression and the central role of the financial system in the crisis, the 1933 Banking Act (aka the Glass-Steagall Act) was the first to specifically address size in the banking sector.

Altogether, over the 36 presidential cycles analyzed, Democratic platforms mentioned monopolies significantly more than Republican platforms: 81 vs. 49. But since 1976–40 years ago–both parties’ interest in monopolies has all but disappeared.

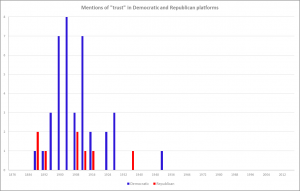

Trusts

Trust (in the sense of business conglomerates) may be considered synonymous to monopolies and sometimes appears next to “combinations” and, to a lesser degree, “pools.” Over time, the word became less used in that specific context, but the analysis makes two things apparent: (1) its mentions peaked at the turn of the 20th century, and (2) Democratic platforms mentioned trusts much more compared with Republican platforms: 38 vs. 8.

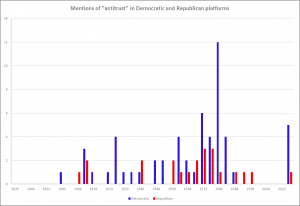

Antitrust

As the means for fighting monopolies–and trusts, specifically–antitrust laws were developed after monopolies and trusts appeared and were evident. The usage of the term “antitrust” began appearing more prominently in political platforms about 10 years after the first antitrust laws were passed. Here too, Democratic platforms mentioned it noticeably more often: 56 vs. 22. The Democratic peak arrived in 1980, when Democratic incumbent Jimmy Carter lost to Republican Ronald Reagan by a huge margin of electoral votes. Notably, in 2016 the Democratic platform mentioned antitrust 5 times,) after not mentioning the word for 28 years.

According to Google Book’s Ngram Viewer, which charts the frequency of words found in printed sources between 1500 and 2008, the word “antitrust” first appeared around 1600. Until around 1900 it was very seldomly used. Mentions picked up in the 20th century, peaking in 1983 (“anti trust” and “anti-trust” appear less frequently).((You can see the results here.)) This pattern is similar to the frequency of these terms in the Democratic and Republican platforms, even though it peaked in the platforms earlier, between 1972 and 1980.

Competition

It was not until the early 1970s that either party mentioned competition in any significant way. Usage peaked in the 1980 and 1984 cycles, in which Ronald Reagan won.

Like “monopoly,” “competition” is not contentious, but is still context-sensitive. Indeed, Republicans used “competition” as a reason to reform regulation and government intervention, but during these years both parties were more worried about foreign competition and America’s global competitiveness, especially versus Japan, and an overvalued dollar.

While the language on “antitrust” in the platforms is almost always used to promote pro-market policies, the use of competition is more ambiguous. Sometimes, it is used in discussion of policies that aim to limit competition and free trade.

In the next installments of this series we will go into details, and look at specific quotes from the last 140 years and their historical, political, and economic contexts.