A new working paper by University of Georgia researchers shows that medical marijuana leads to sharp drops in the number of prescriptions for branded drugs.The paper estimates savings of up to $1.5 billion per year in Medicaid spending if medical marijuana was legalized in all 50 states. The ideas of the late University of Chicago economist George Stigler might offer a potential explanation of why this has not happened yet.

In May, a survey conducted by Quinnipiac University found overwhelming support for the legalization of medical marijuana among American voters: 89 percent of respondents said they support the legal use of marijuana for medical purposes by adults, as long as a doctor prescribes it. The poll also found that support for legalizing medical marijuana was 79 percent or higher across parties, genders, ages, and racial groups.

The Quinnipiac poll is not an outlier. Polls have consistently shown in recent years that a majority of Americans support the decriminalization of marijuana, in conjunction with a growing demand for medical marijuana from consumers, some of whom may use it as an alternative to expensive prescription drugs.

Despite this overwhelming public support, medical marijuana has only been approved in 25 states (plus the District of Columbia) since 1996, when California became the first state to institute a medical marijuana program. Federally, marijuana is still classified as a Schedule 1 drug, the most restrictive classification under the Controlled Substances Act, which deems it a dangerous drug (akin to heroin) that has no accepted medical use. Recently, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) rejected a recommendation by the Department of Health and Human Services to reclassify marijuana as a Schedule 3 drug, a far less restrictive category.

Why, in the face of widespread support from voters, has the will of the people not been implemented? Some, including journalist Lee Fang and the Washington Post’s Christopher Ingraham, have suggested that this might have something to do with resistance from pharmaceutical companies, longtime rivals of marijuana reforms. Pharmaceutical companies have lobbied against marijuana legalization on both the state and federal level, and spent millions on anti-legalization campaigns and funding for academic research that presented marijuana as dangerous.

A father-daughter team of University of Georgia researchers, W. David Bradford and Ashley Bradford, recently showed why pharmaceutical companies might be wary of legalized marijuana: in states that instituted medical marijuana programs, legalization was followed by a sharp drop in the number of prescriptions for branded drugs for which marijuana could be used as an alternative.

A father-daughter team of University of Georgia researchers, W. David Bradford and Ashley Bradford, recently showed why pharmaceutical companies might be wary of legalized marijuana: in states that instituted medical marijuana programs, legalization was followed by a sharp drop in the number of prescriptions for branded drugs for which marijuana could be used as an alternative.

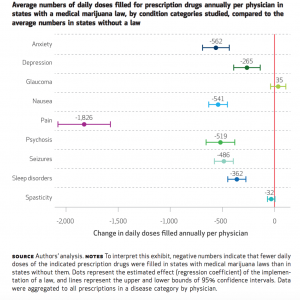

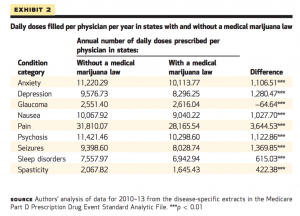

In July, the Bradfords published a first-of-its-kind paper that examined the effects of legalized medical marijuana on doctors’ prescribing patterns by examining data from the Medicare Part D database between 2010 and 2013.((Ashley C. Bradford and W. David Bradford, “Medical Marijuana Laws Reduce Prescription Medication Use In Medicare Part D,” Health Affairs 35, no. 7 (2016): 1230–1236.)) Their paper focused on nine categories of drugs: pain (sales-wise, the most lucrative category for pharmaceutical firms), anxiety, depression, glaucoma, nausea, psychosis, seizures, sleep disorders, and spasticity. They found that the 17 states that had medical marijuana programs in 2013 have seen a sharp drop in the number of prescriptions, particularly for painkillers. In states where medical marijuana was legal, doctors prescribed 1,826 fewer daily doses of painkillers per year, 562 fewer daily doses of anti-anxiety drugs, and 265 fewer daily doses of antidepressants.

The Bradfords have since utilized the same methodology and applied it to Medicaid, where the population is younger and therefore more prone to use medical marijuana.((Craig Reinarman, Helen Nunberg, Fran Lanthier, and Tom Heddleston, “Who are Medical Marijuana Patients? Population Characteristics From Nine California Assessment Clinics,” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 43 (2011):128–35.)) In a new working paper, they find that the trends they observed in their previous paper were much more pronounced, and that medical marijuana was followed by a drop of 3-5 percent in the number of prescription in seven of the nine categories they examined.((Ashley C. Bradford and W. David Bradford, “State Medical Marijuana Laws and Prescription Drug Use in Medicaid,” (forthcoming).))

The Bradfords’ research also indicates that legalizing medical marijuana could benefit taxpayers, in the form of reduced spending on health care. States that legalized medical marijuana by 2013 saved $165.2 million per year on Medicare spending alone, according to their research. If all states had implemented medical marijuana laws in 2013, they estimated, overall savings to Medicare would have been $468 million—just under 0.5 percent of all Medicare Part D spending in 2013. When it comes to Medicaid, the savings are much larger, and could be as high as $686 million.((While many states rely on managed care Medicaid contracts, the Bradfords only examined data on fee-for-service Medicaid prescriptions, because managed care programs vary from state to state. Since their estimations did not include managed care spending, the Bradfords believe their estimations regarding potential savings to be conservative.)) If all 50 states had legalized medical marijuana by 2014, according to their estimates, that could translate to savings of $1.5 billion per year in Medicaid spending.

Given that public support is overwhelming and that it might lead to significant savings, one would expect politicians and regulators to enthusiastically be in favor of further liberalization of marijuana laws. Some politicians, such as presidential frontrunner Hillary Clinton, have expressed support for the legal use of marijuana for medical purposes, but others remain resistant. There are, of course, legitimate reasons to resist the legalization of medical marijuana, despite its possible benefits. However, the ideas of the late University of Chicago economist George Stigler might offer a potential explanation for why medical marijuana has not yet been approved in all 50 states.

Medical Marijuana and regulatory capture

More than 40 years ago, Stigler introduced the theory of regulatory capture, and with it the idea that regulation can be acquired by special interest groups who wish to subvert competition by creating barriers to entry.((George J. Stigler, “The Theory of Economic Regulation,” The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 2 (1971): 3-21.)) The resistance of pharmaceutical companies to marijuana reform seems like it could serve as case in point.

The pharmaceutical industry is one of the biggest lobbies in Washington, having spent over $240 million on lobbying in 2015 and nearly $3 billion on lobbying since 1998—more than the oil industry, the auto sector, and the real estate industry combined. According to a 2014 study by the Center for Responsive Politics, the pharmaceutical industry was among the leading forces lobbying against marijuana reforms.

Had the DEA decided to reclassify the federal status of marijuana, the decision would have little effect on the ability of physicians to prescribe marijuana-based drugs to patients sans FDA approval, but would have meant an official acknowledgement that marijuana could have therapeutic value. For this reason, it encountered resistance from some pharmaceutical firms. Prior to the recent DEA decision to not reschedule the federal status of marijuana, Christopher Ingraham reported that “at least one drug company that manufactures a synthetic version of THC—which would presumably have to compete with any natural derivatives—wrote to the Drug Enforcement Administration to express opposition to rescheduling natural THC, citing ‘the abuse potential in terms of the need to grow and cultivate substantial crops of marijuana in the United States.’”

Could regulatory capture be a factor in preventing the full legalization of medical marijuana? In a recent conversation with ProMarket, W. David Bradford said that while he and his daughter didn’t write their initial paper with regulatory capture in mind, they have “come around” to the view that pharmaceutical companies are opposed to reforming marijuana laws.

“The biggest reaction we’ve gotten to this paper, that I hadn’t anticipated, was that people interpreted our results as if we were providing evidence for why pharmaceutical companies would oppose the legalization of marijuana. Having now looked at the issue more since our paper came out, I do think we are seeing activities on the part of the pharmaceutical industry to protect their interest in mostly-branded drugs that treat these conditions,” he said.

The Bradfords’ two papers show that people use marijuana as medicine, and not just recreationally. They also seemingly show that pharmaceutical firms have a reason to worry about further liberalization of marijuana laws. Yet initially, Bradford said, he was “really skeptical” of the notion that the pharmaceutical industry would oppose legalization.

“I thought ‘why would pharmaceutical companies oppose this? If they could get a new drug approved based on whole-plant marijuana, and it was a blockbuster, they could get at least five years of exclusivity out of it, and lots of patent protection if it was a patentable product.’ But after thinking about it more, and being made aware of the amount of money that pharmaceutical companies are spending to lobby against marijuana legalization, I’ve come around to the view that it’s not likely that whole-plant could be patentable, or gain any kind of market exclusivity from the FDA. Even if you could somehow short-circuit some of the trials, it’s still going to cost hundreds of millions of dollars to get a drug through the FDA approval process. And if it’s a whole-plant product, and it is proven to work, and it gets approved and is rescheduled somehow, and then people could just grow it in their backyards, what’s their incentive?” said Bradford.

The pharmaceutical industry has not completely turned its back on marijuana. According to a report by Viridian Capital Advisors, an advisory firm to the cannabis industry, Biotech firms like GW Pharmaceuticals were responsible for more than half of the capital raised by the industry in 2015. Epidiolex, a drug based on cannabidiol (an ingredient found in cannabis, also known as CBD) used to treat childhood-onset epilepsy, is currently nearing FDA approval.

“There are currently at least two drugs that are CBD derivatives that are nearing approval. These are typical products, like any drug that manufacturers would make from any other plant they find in the Amazon,” said Bradford. While pharmaceuticals remain opposed to full legalization of marijuana, he added, the isolation of particular ingredients enables them to maintain market exclusivity.

“I can definitely see the argument that the pharmaceutical industry prefers to take the path that’s open to it at the moment, which is isolate a molecule from marijuana, develop it into a drug, patent it, get exclusivity, and you’re off and running,” said Bradford. “Allowing whole-plant legalization might be a threat to their business model.”