In the second part of ProMarket’s interview with Bo Rothstein, the Swedish political scientist discusses corruption, social trust and unions.

After decades in which the major economic dispute between conservatives and liberals was heavily focused on the size of government, a new discourse is gaining ground in this presidential election race: not the size but the quality of government. Is it working for the public or for special interest groups? From Donald Trump to Bernie Sanders, from Hillary Clinton to Ted Cruz, “the economy is rigged” has become a leading mantra.

The quest for an efficient and high-quality government, and the lack of it, can explain the mixed message or even dichotomy of the electorate: on the one hand, many people want the government to protect them from some effects of the market economy, and on the other hand, most of them despise “Washington” and the establishment.

The new discourse does not occur only in the general population; since the financial crisis there is much more focus among economists and other scholars on the role of regulation in a market economy. Both conservative and liberal economists agree that that in order to reach desirable outcomes, markets need a set of institutions, formal and informal. The welfare effects of markets is dependent on the efficiency of those institutions.

Conservative economist John Cochrane from Stanford summarized recently in a paper on growth((John H. Cochrane, 2015. “The Election’s Most Important Issue.” www.hoover.org/research/elections-most-important-issue)): “Regulation is not more or less, regulation is effective or ineffective, smarter or dumber, full of unintended consequences or well- designed, captured by industry or effective, based on rules or based on regulator whim, accountable or arbitrary, evaluated by rigorous cost benefit standards or by political winds, distorting economic activity or supporting it, and so forth.”

While there is vast literature on the way financial markets and markets in general operate, the literature on the formal and informal institutions that set the rules of the game in those markets is more modest. Even when you step outside of the economic literature to political science and other disciplines, most scholars focus their research on voters, parties, elections, and opinions rather than on the efficiency and quality of the government and regulation. Because of the incredible influence that informal institutions have on the quality and integrity of regulation, we intend to interview more political scientists on this subject in the coming months.

(Note: this is the second part of Guy Rolnik’s interview with Bo Rothstein. The first part can be read here)

Guy: You mentioned “the market” many times. Some readers, especially from the U.S., may associate your interest in government with not believing in capitalism.

Bo: Capitalism and markets are two different things. How should I say it? In a market economy, those who own capital can hire labor. Then, if you hire labor, if you employ people, you decide what is going to happen on the production side.

In a market economy, labor can hire capital. You and I can start a small consulting firm. We have no money, we go to the bank, we get the loan because we are credible, but the bank doesn’t decide what we do. We decide. Many companies [have] equity plans for employees. Production now is so complex, so this standard model of capitalism doesn’t work so well anymore in the sense that you cannot have the knowledge of what to do. Think of high tech companies, or complicated medical operations, or consulting firms. People who actually own the shares cannot steer them, because they don’t have the knowledge. All of the interesting capital has moved away from physical things, machines, and into the mindset of people.

You have the shift of balance here, which I think is a little interesting. The power of, how should I say, the knowledge class becomes an increasingly important asset in production.

G: Still, the market economy in Sweden is much different than the one in the U.S.

B: Yes, I would call it organized capitalism. It’s not that it’s not highly regulated, but it’s highly regulated in a way that will increase global competition. The social democratic countries like Sweden and Denmark are small countries. They know that their only possibility to prosper, and remain prosperous, is if their economies are globally competitive.

They also know that there is no way they would be able to compete with low wage countries in East Asia, so the only way they can compete is with high competence, innovation, creativity, and so on. What do they do? They put a phenomenal amount of money into human capital production, research, training, and early vocational training.

One of the best investments in these countries are the preschools, because it turns out that what happens during your first one, two, three, four years, cognitively, has huge importance. Preschool teachers in these countries, they have a three-year college education. It’s not babysitting, they are actually educated.

That is what they do. They’re not unregulated in any way, but regulations are always thought of as striving to achieve global competitiveness.

Solving a problem of collective action

G: So the idea is to combine market economy with welfare state?

B: There are various ways to think about the welfare state. One is to think about the welfare state as taking care of the poor in kind of an altruistic way. Another way to think about the welfare state is that it’s a power game, the left against the right and redistribution.

I have tried to launch a third way of thinking about the welfare state. You can think of it as solving a problem of collective action. In many areas—say, pensions, healthcare, unemployment insurance—markets, because of asymmetric information, will not deliver, or will deliver much more inefficiently.

There are, for example, no private insurance companies that would ensure your pensions against inflation. They cannot, it’s impossible. We know that, in healthcare, that markets tend to push to over‑billing and over‑treatment to a very high extent. That is what explains in large part why, in the U.S., healthcare expenditure is much higher than in Europe.

If you bring the middle class into the system in a way that provides reasonably good schools, free tuition, and reasonably good healthcare, they will be willing to pay taxes because it’s actually beneficial for them to have this taken out of their private market.

Through that, you will also provide these services to low-resource members of society. The best way to help the poor is not to talk about them, in the sense that you shouldn’t have special programs for poor people, because special programs for poor people become poor programs.

However, the middle class won’t accept the services if they’re not reasonably high quality. The middle class is important because that’s where the money is. In order for this pact to work, you need to solve three trust problems: First, you must actually trust that most people are actually paying their taxes. Secondly, you must trust that there is not a huge amount of abuse or overuse of insurance services. And finally, you must trust that, when the service is actually delivered, it will be done in a way that is good for you, that addresses your sense of integrity.

You don’t want to be treated like a sheep in the healthcare or elderly care systems. This trust will only come about if people perceive that there is reasonably high quality in the administration.

In many countries, people would say, “I would like to see more public goods, I would like to see better public services, but I simply distrust the administration, whether in stealing taxes or by not delivering the services in an acceptable way.”

I think of the welfare state more like solving the collective action problem for the middle class.

Strong markets, a strong state

G: Let me run by you the following proposition that might be agreeable to both camps, the left and the right: a market economy is usually the best way to allocate resources and to advance the economy, but in order to have a legitimate market economy, we need efficient regulation and social safety nets. In order to have those, we need to have a public administration that is not corrupt and that is very capable.

B: I couldn’t agree more. That’s basically my position. I agree with most people who are economists and are enamored with markets. We haven’t found any better way to handle the allocation problem than markets. But I disagree when they say we need a minimal, or a very small state, or that the state is not important.

This is what the Nordic countries, but also Germany and the Netherlands and many other countries, actually show. You can have societies with quite strong markets but also quite strong states.

The Swedish state is not small—we pay very high taxes. But over the last 20 years, the support for the basic welfare state system has not eroded. On the contrary, the support among the middle class has increased. This is because they feel they can get benefits—they get their money back.

G: Many people are not aware that Sweden, the leading social democratic model in the world, is actually also a big supporter not only of competition and markets but also of using the tools of privatization. How does this work?

B: Privatization is a tricky concept. Every productive activity should consider three things. One is how is it financed, the second is who is regulating it, and the third is who is actually producing the service. Each of these things can be private or public.

It’s not so easy to say what is private and public. If you privatize something, you also have to be able to say what is important for you. We want the garbage collected and that the buses will come on time. We can usually measure that quite well.

But in other cases, like education or health, it is much more complicated. It’s much, much more difficult to write a clear contract. If you cannot formulate a clear contract and you create a for-profit company to provide the service—the natural thing for market-based entities is to cut corners, of course. Sometimes you can have the benefits of competition without profits. Chicago University is competing with Harvard, and Yale, and Stanford, and so on, but none of them are driven by profits. There is no owner who takes out money from these organizations.

G: But here is the problem again: if you want privatization of such services to work, you need to have effective regulation.

B: Yes, that’s very clear. That’s why I said that writing and enforcing contracts is very complicated. You need un‑corrupt and quite competent and efficient people in the public sector.

If you don’t have the right to choose between providers, which was the case in Sweden until the early 1990s, then you create what I’ve called a “black hole” in the democracy. Because if your kid is bullied in school or if your grandmother gets very badly treated at the elderly care center, you can, of course, complain, but if you cannot go to another provider, this can create huge problems in your life.

We have public services because they are very important to us. And therefore, from a normative standpoint, we need to have a choice. This is also supported by organizational theory: organizations that don’t get one signal when they do something wrong and another signal when they do something right will, in the long run, do more wrong things than right. Losing customers or clients is a very important signal.

G: Where do you want to see competition in services that are provided by the government?

B: I’m talking about service providers here: healthcare, education, elderly care, preschoolers, buses, garbage collection.

|

The contract problem

G: Many people from the left might be surprised: you want to see competition in public goods and you are a social democratic Swede?

B: I wrote about this in my book about the welfare state. There is a chapter where I discuss it. Even if you are a supporter of a broad‑based welfare system, you shouldn’t say no to competition and private providers, conditioned on those things I said.

I’m not 100 percent opposed to for‑profit, but I think that if you allow for‑profit provision in these areas where the process is important, you have to be very skilled in how you write the contract: think about writing a contract stipulating that elderly people should be respected when they are taken care of.

How do you write such a contract? It’s easy to write a contract about buses. The buses should go here, they should go there, this is the number of buses, and these are the safety regulations. But how would you write a contract about how you should actually take care of preschool children, for example?

G: Let’s go back to the basics. You use in your papers and books the phrase “quality of government.” And you define it as “impartiality” of the civil servant.

B: I was very unhappy with the standard definition of corruption. Corruption must be the opposite to quality, right? The standard definition of abuse of public power is so broad. This is a completely empty definition because abuse is not defined.

You don’t know what abuse is. You don’t know what is the norm that is transgressed when corruption occurs. This has a number of bad implications. First, it invites all kinds of Interpretations. What is perceived as corruption in Denmark is something completely different than in France, or Nigeria, which is not good.

Secondly, it empties the whole discussion. If you think about democracy, we know that democracies are based on one, and only one, basic norm: political equality. Everyone has the same right to vote, everyone has the same right to free speech, everyone has the same right to be elected for office. It’s not perfect, but this is the norm.

While it is relatively easy to spot corruption on the input side, it’s much more complex on the output side – the side where actual decisions are made by those who hold public positions. It couldn’t be equality, because kids with learning disabilities need much more attention than kids without learning disabilities. People with serious illness need much more medical care than others.

It couldn’t be equality. Then we were inspired by the famous political philosopher John Rawls and the idea about impartiality. Impartiality means that when a public official is implementing something, he or she cannot take into account your political affiliation or your ethnicity, or whatever that is not stipulated in the law.

G: Impartiality is, in a way, mentioning Rawls, a way to look at what you would have done if you were behind the veil of ignorance.

B: Exactly. Then, for example, why does impartiality translate into high competence? The reason is that the logic following from impartiality is meritocracy. When you recruit and promote people in the state, it’s their actual competence that you consider.

By this, you get a number of people who basically know more. You get higher competence in the system. Many economists say you cannot speak of quality of government without taking efficiency or effectiveness into account, but I say no, this is not so.

We want to explain efficiency and effectiveness. If you add that into the definition, you can. We have now very good data on this. We can show that you can measure impartiality, and it has its expected outcomes. Countries with the more impartial administration perform better.

G: When you look at quality of government in the rich world, what do you see?

B: If you just take Europe, you see huge variations between Greece and Denmark, Hungary and Great Britain, or Norway and Portugal. It’s amazing how big the differences are. But then, even more interestingly, maybe it’s not only country differences.

In some of the countries within Europe, you see quite high regional differences. You can have a country with some regions that are pretty clean and some regions that are really bad. Italy, for example. Again, we have to think about the very little clout you get from formal institutions. Italy has had the same formal institutions for 150 years. When it comes to quality of government and corruption at the regional level, it gives you nothing.

The corrupt country with perfect institutions

G: Would you agree that there is always talk about setting the right institutions and introducing “reforms”—and very little attention to the informal institutions?

B: Uganda, one of the world’s most corrupt countries, according to the World Bank’s measure, has almost perfect institutions. This is why Douglass North was fundamentally right. You cannot concentrate only on the formal institutions. You have to see two things. First is what are the informal institutions and secondly the formal institutions—how do they actually operate in practice when they reach the field?

G: Let’s talk about informal institutions, norms, and value. Let’s start with some definitions. You talk a lot about social trust. Some people talk about social capital, or civic trust. Can you help us?

B: It’s basically terminological. They are not conceptual things. I would say people who talk about social capital usually include networks. You can say social capital is the number of people you know, multiplied by the level of trust in these relationships. It cannot be a big asset to have enormous trust but in very, very few people. It’s better to have reasonably high trust in a lot of people. Most people get what they need in life through their networks. New jobs, apartments, relationships, tips about good restaurants or good places to visit when you have a vacation, all kinds of things.

G: How do we measure social trust?

B: There is no perfect measurement, of course. Internationally, I

think it started with the general social survey, back in 1962, in the U.S. that asked this question: “In general, do you think most people can be trusted?” It spread to the World Values Survey, and so on.

They had this dichotomy, either you trust or you don’t trust. We have a scale of 0 to 10, because we think it’s not the case that you totally trust people or you totally distrust them. We use a 0 to 10 scale instead. Of course, it’s better that you get more realism into your regression analysis when you have a scale.

Is this a perfect measure? No, nothing is perfect here, but this measure constantly correlates with a number of valued outcomes. Countries with a high level of social trust among their population perform better in almost every way. Economically, democratically, they have lower crime and less corruption.

The case of garbage sorting

G: If I bring you in as my policy advisor to any country in the rich world and I want you to help us increase quality of life, what would you tell me? Fight corruption? Have meritocratic government?

B: Most anti‑corruption efforts have been driven by this “principle-agency” theory. The idea is that you have the honest principle, and then the agents are opportunistic, or maybe even dishonest. The trick in this model of fixing corruption is that the honest principle changes the incentive for the agent.

When fear of being caught for corruption is higher than greed, things will go better. You go for stricter laws, more punishment, more inspectors, and so on.

This turns out not to work for two reasons. First, if corruption was a problem of incentives, we would’ve fixed it long ago. Secondly, in a systemically corrupt country or city, where should this honest principle come from? Who should that be? It’s an extremely unlikely figure to assess. This means that the people who are going to change incentives, or monitor the incentives, don’t have an incentive to change or monitor the incentives. They can be bought off. They are the ones who are most ripe for corruption.

This theory of principal-agency has led most of the corruption industry in history. I’m not saying that laws and regulations aren’t important, but they must be secondary. The most important thing is to change what you could say is the perception people have of the social contract in society.

This is based on this general idea that people are basically not rational, self‑interested, utility maximizers. There are such people, but they are actually a minority. Most people still base their moral outlook on reciprocity. They’re willing to do the right thing, but only under some assurance that most other people in their situation are also willing to do the right thing.

You’re willing to go an extra step to sort your garbage, but it makes little sense if you’re the only one. The good that’s going to be produced, or might be produced, will have this constant free rider problem.

This means, of course, that the signals, if you want to change such an equilibrium, must be quite strong. They must be so strong that not only you think that you should change, but you think that most other people in your situation have to change as well.

These are things we found empirically, the things that seems to work: a reasonably broad‑based system of taxation. When people don’t pay taxes, they don’t care about corruption. Meritocracy seems to work very well. In most countries, you get a position in the public sector because you belong to the right party, the right family, or because you’re a man.

If you change that and say, “No, we’re now going to go for strict meritocracy,” this is a revolution.

G: When people hear you and others talk about meritocratic quality government and no corruption, many times the response would be that this is irrelevant for most countries. It can happen only in homogeneous countries like Sweden.

B: It’s becoming an extremely multicultural country. I think that currently some 20 percent of Swedes have at least one parent who is foreign.

G: Yes, but it was such a more homogeneous society for so many years and developed a very strong culture. Now, the people that come to Sweden basically adopt that culture, but when you start with many societies that are heterogeneous, like the U.S., that has been an immigrant society for many years.

G: Yes, but it was such a more homogeneous society for so many years and developed a very strong culture. Now, the people that come to Sweden basically adopt that culture, but when you start with many societies that are heterogeneous, like the U.S., that has been an immigrant society for many years.

B: It’s more difficult. I mean, of course, ethnic diversity is challenging, but there is a very nice meta‑analysis of this. It was done by a young German political scientist. He studied some 180 studies with 480 results, asking the question, “Is ethnic diversity bad for social cohesion?”

Some data point to a link between ethnic diversity and social cohesion, but even so it’s only 60/40.

G: If it’s not ethnicity, what is it that explains the difference in social trust?

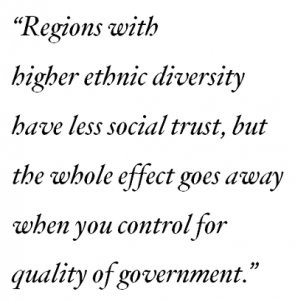

B: We have just finished a paper about this. It’s unbelievable. We have data about social trust and levels of quality of government for some 200 regions. We have data about unemployment, about income differences and civil society. We also have data on how many inhabitants in each region are born outside it. When we do the regression analysis, what we find is the following: yes, regions with higher ethnic diversity have less social trust, but the whole effect goes away when you control for quality of government.

In regions with high quality of government, ethnic diversity doesn’t have a negative effect on social trust. We theorize this in the following way: you live in a region, or a city. In comes quite a number of people who are not like you. They speak a different language, they look different, they have a different faith. You also know that there is no quality government. The taxation authorities, healthcare, and social services are wishy‑washy.

They don’t pay taxes, they overuse the welfare system, they engage in criminality, the police don’t handle them, and so on. Then you lose trust. Think of Hungary, Britain, and Spain. However, if you live in Copenhagen, you’re more likely to say, “Yeah, here comes a number of people that are not like me. I may not even like them. I would like them not to come.” But because there is reasonably high-quality government, you say, “They are different, but they actually have to play by the same rules.” Then th

e trust problem goes away.

G: You believe that in countries and regions where you have different ethnicities we, theoretically, can have social trust and quality governments?

B: I don’t think ethnic diversity, as such, leads to the destruction of quality government. What I am saying is that if quality of government is bad, then social cohesion will take a hit from ethnic diversity. If you can shore up quality of government, ethnic diversity will not be a problem.

Take immigrants to Denmark, for example. Denmark has very good data and it is a country that has high trust levels. It’s actually gone up in the last 20 years. What happens with immigrants from very low trust societies?

After a number of years in Denmark, their trust goes up. Not to the extreme, high Danish level, but closer to the Danish level than in their country of origin. For this to occur, they need to perceive that they have been evenhandedly and fairly treated by the Danish authorities.

Guy: So the answer is yes?

B: Yes. When you come from Bangladesh, from Turkey, or Pakistan, you know that basically all public officials in your home country are corrupt, dishonest, and discriminatory.

Then you come to Denmark and you experience the opposite. They don’t take bribes. They’re not perfect, but they are not engaged in systemic discrimination. They are quite competent. When you make up your mind about the society, [that it] has a high or low moral standard, it is your perception of public officials that counts.

G: Many students of Friedman and Hayek would find most of your work redundant. Why engage in endless pursuit of getting meritocracy when all you need is to limit government? What would you answer them?

B: Why don’t you start with having a look at the data in the countries with large and quality government. That’s the simple answer. I’m not saying that the Nordic and Northern European model is perfect, but if you make a methodic analysis of all the rankings we have—population, creativity, prosperity —they come out basically at the top.

Big countries too

G: But again, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland are small countries.

B: Take Social Security in the U.S. It works basically like Denmark. It’s a universal system, it has high legitimacy, the middle class is on board. No Republican government have been able to touch it. Take National Health Service in the UK, the same.

Solidarity is, for me, is something that is not naturally determined. It’s designed by how you design the systems. Rawls has the best formulation. He says, “A just system will generate its own support. What I’m saying is that Danish systems or Swedish systems work. They can work even in much more neo-liberal countries.

G: In the U.S., the highest institution of justice is very political. It is this Supreme Court that allowed, through “Citizens United,” to legitimize money in politics.

B: This ruling from the Supreme Court was disastrous. I’m not very much in favor of very strong judicial review. For me, from what I see around the world, in most cases judicial review is just politics by unelected people.

That creates huge legitimacy problems. Democracy, at the end of the day, relies on legitimacy. If you are outvoted, you should accept that you’re outvoted. If it’s a decision by unelected judges, why should you accept that?

G: What is the role of unions in the public sector in quality government? In many countries they are perceived as a big part of the problem—another special interest groups that protects its people.

B: When people use the term “unions” here and in the Nordic countries, they mean completely different things. Everything is different. It’s very difficult to compare. This is a problem in all comparative politics. The term is the same, but when you compare them, they’re actually like apples and pears. I’ve never heard of people coming to a union meeting in Sweden. You don’t do that.

G: In Sweden and Denmark, 60 percent to 80 percent of labor is unionized, so unions have to be responsible and internalize the need for efficiency and productivity. Is this the missing ingredient from other countries?

B: You can say that a union that is very small can act in a very irresponsible way because the costs of the irresponsibility are spread, but if you have a union that organizes 70 percent, there is no other way. You cannot drive away the costs to someone else. It’s quite logical. There is a very much cited paper by Claus Schnabel and Joachim Wagner about a curve that is U-shaped((Claus Schnabel and Joachim Wagner. 2008. “Union Membership and Age: The Inverted U-Shape Hypothesis under Test.” University of Lüneburg, Working Paper Series in Economics, No. 107)): if you have very weak unions, that’s good for the economy. If you have very strong unions, that’s also good for the economy. The worst thing is if you are in between, because then the unions are strong enough to go on strikes many times and issue demands, but they don’t take responsibility.

In Sweden, for instance, I think some 75 percent of the workforce in Sweden, maybe even 80 percent, is unionized. There is no way for the unions to free ride on others; there is no other group that will take the cost for low productivity and inefficiency If inefficiency builds up inside the company whose workers are unionized. If you have a union that only organizes a small fraction, they can collect all the rent because other people are taking the costs. What do they care?

When you are a small union, it’s a nice little cartel. That’s how you think about it. If it’s big, you cannot play that game. You know that if you would come with demands that are too big, all your members will suffer, so you have to be responsible.